The Early History of the Accademia di San Luca

Explore research and scholarly essays about the Accademia di San Luca in Rome—one of the first academies of painters, sculptors, and architects, founded in 1593.

Initiated in 2010, this project is a collaboration of the National Gallery’s Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts in association with the Archivio di Stato di Roma and the Accademia Nazionale di San Luca.

News

August 2025

In 2025–2026 the project will adapt to new scholarly publication models intended for academic audiences and for greater accessibility. During this transition a web recorded version of the project website is available at the Internet Archive. Please note that certain features like search and image zoom will not work on the archived site.

Questions or feedback? Get in touch with us: [email protected].

Resources

Visit current resources and anticipate upcoming features.

Documents and Transcriptions – coming soon

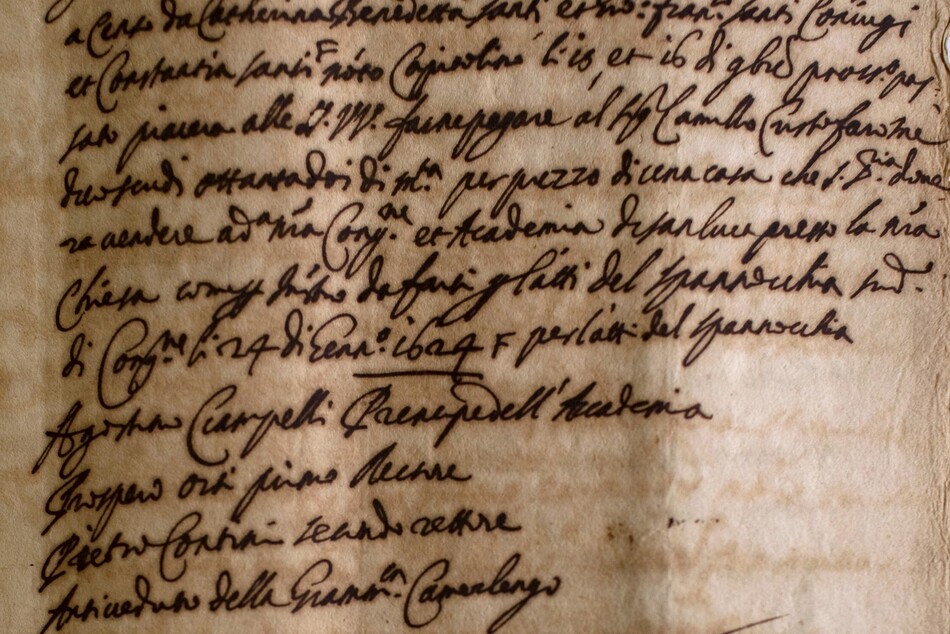

Search and browse transcriptions of notarial documents from the 16th and 17th centuries preserved in Roman archives.

Research and Publications – coming soon

Read scholarly essays on key issues and events made possible by new research using archival document transcriptions.

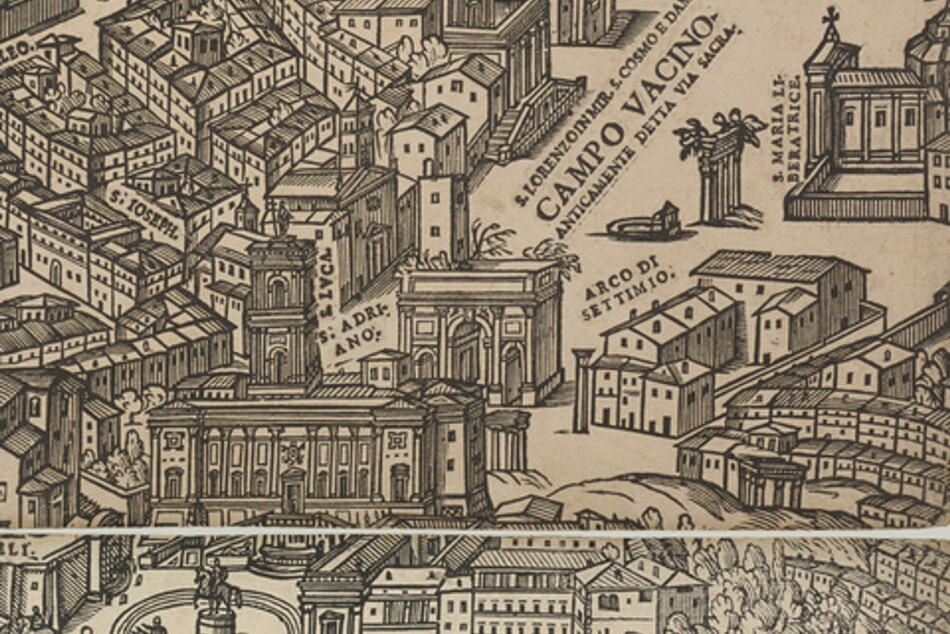

Maps and Guidebooks – coming soon

Explore historical maps and guidebooks that highlight places important to the Accademia’s development.

Bibliography

Search and sort a database of bibliographical resources on the history of the Accademia and its most prominent members.

In our collection

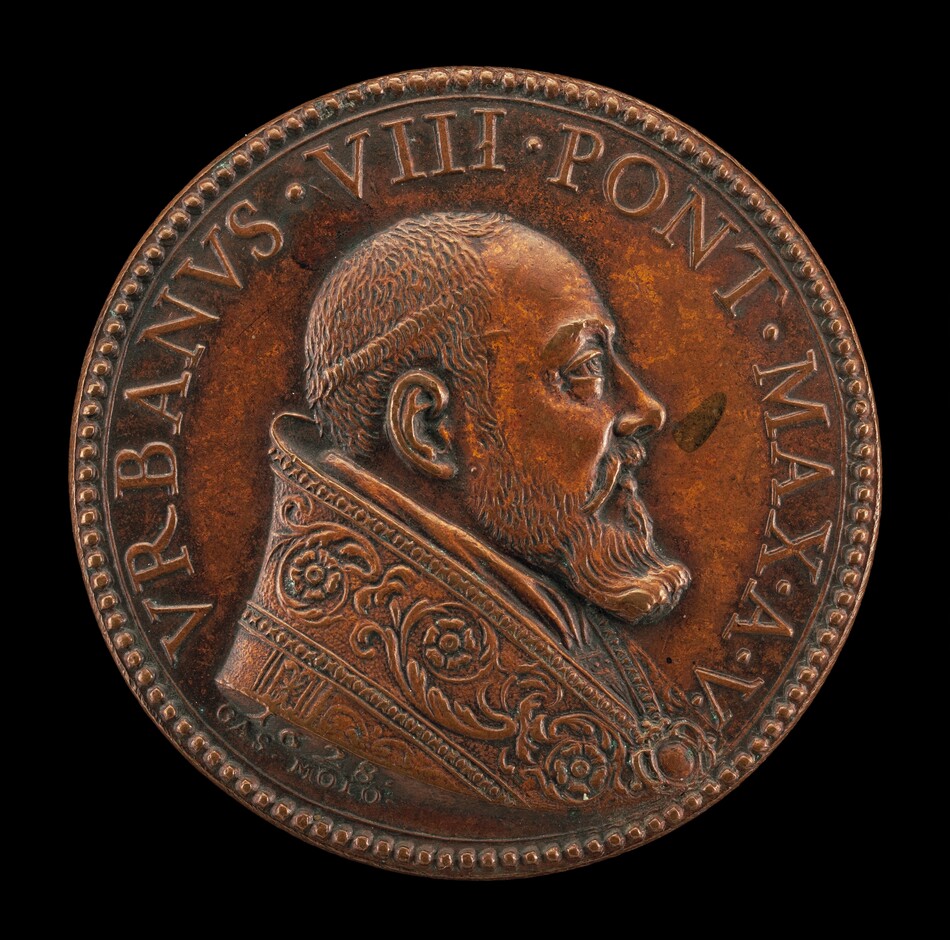

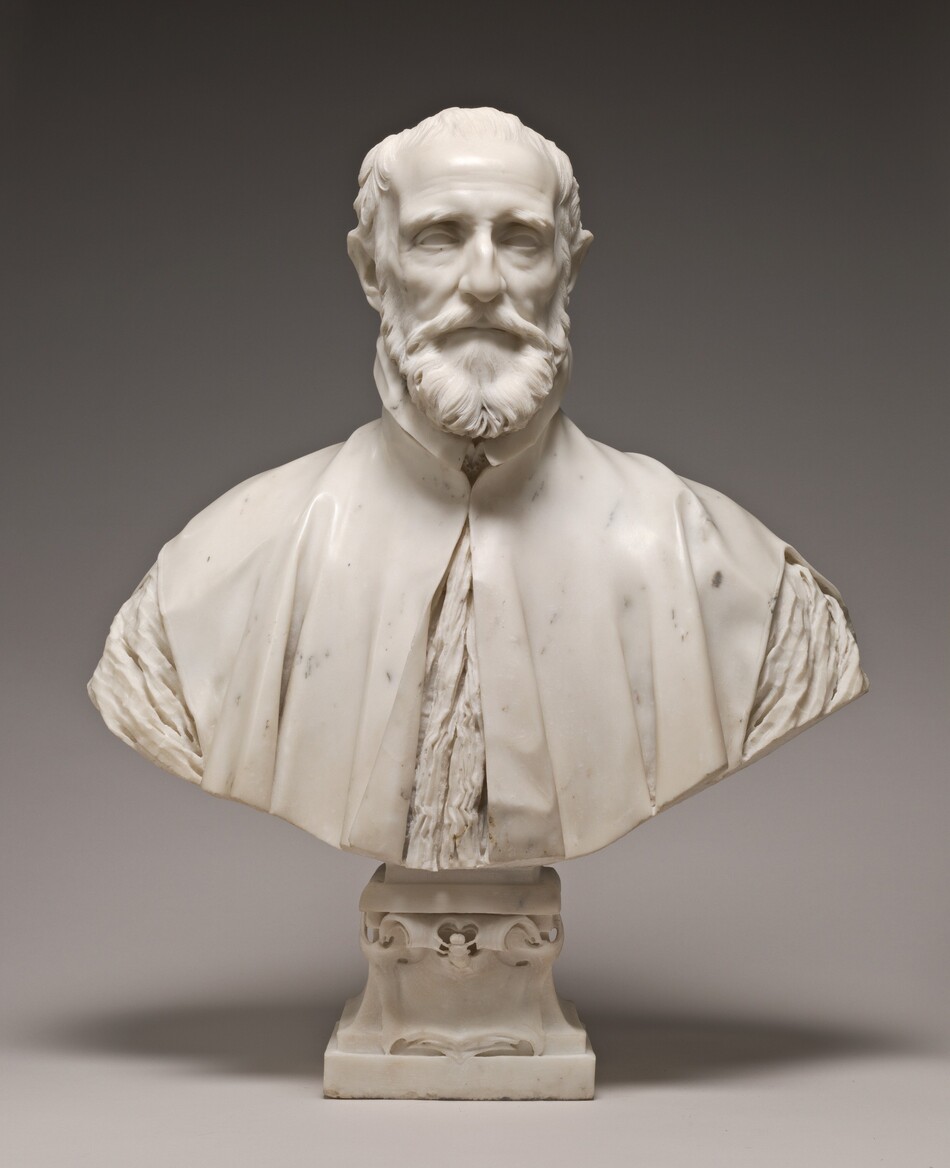

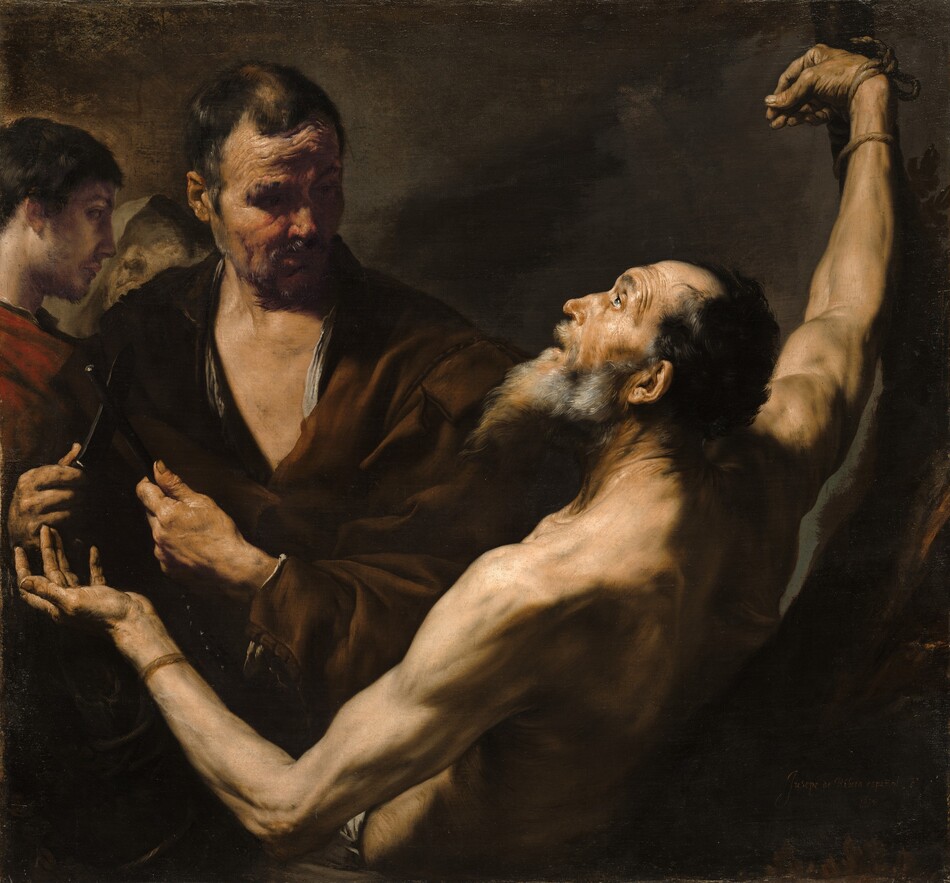

Many of the artists who participated in the Accademia di San Luca from 1590 through the 1600s are represented by works of art in our collection.

About the project

The Early History of the Accademia di San Luca was conceived, under the direction of associate dean Peter M. Lukehart, as a project in two parts: a volume of essays concerning the establishment of the Accademia and a database of rediscovered notarial documents that support current and future study of the Accademia and its members.