There is a growing body of literature on so-called unofficial visual artists and artist collectives who worked in numerous places across the former Eastern Europe, most often creating small, tight-knit communities where they could explore alternative ways of making art and perceiving the world. There exists as yet, however, no broad account of the role that filmmaking played for different artists in their individual practices or of the role that it could play in bringing members of different “unofficial” or underground cultural circles together. This program showcases the variety of film projects made by or with artists in the former Eastern Europe and highlights how filmmaking—an activity that favors collaboration—could capture and strengthen a sense of community for the participants.

Banner stills L to R: Somnambulists, courtesy Filmoteka Muzeum; Drawings, courtesy Vladimír Havrilla and Boris Kršňák;

Transformations: Potter's Bull, courtesy DEFA Film Library at the University of Massachusetts Amherst

Artists, Collectives, and Communities

Still from Drawings, courtesy Vladimír Havrilla and Boris Kršňák

The two earliest films in the program date to the 1950s and reveal the influence of the Polish artistic polymath Tadeusz Kantor, who began his creative life as a painter but over time became best known as an experimental theater director and stage designer. He also made sculptural objects, orchestrated Happenings, and helped found the Kraków Group of avant-garde artists in his adopted hometown. Though he did not make either of the two films, both Andrzej Pawłowski (Cinéforms) and Mieczysław Waśkowski (Somnambulists) were influenced by his ideas. Pawłowski belonged to the Kraków Group and staged performances of live light shows for several years before turning them into an abstract film.[1] Waśkowski worked with Kantor to make the film Attention! Painting (now lost) about Kantor’s creative process as a painter before making Somnambulists, for which Kantor was a consultant, later the same year.[2] Both films demonstrate the willingness of their makers to work between and across media, heeding Kantor’s emphasis on the “importance of experimentation.” Somnambulists in particular uses film to bring to life in eerie and stunningly beautiful, biomorphic ways the “vibrating spots of paint, lines and colours” that also characterized Kantor’s tachist or art informel paintings from this period, which he described as “‘secretions’ of his inner self.”

Tadeusz Kantor is emblematic of an Eastern European artist whose ambivalent relationship to engagement with politics shifted and evolved over a long career. In their total abstraction, Cinéforms and Somnambulists echo Kantor’s self-proclaimed disinterest in commenting on any social matters from the late 1940s until the mid-1950s, even though abstract art was politicized and persecuted by Polish authorities during the heyday of socialist realism. By the late 1950s, however, abstract art was not only permitted but widely accepted in Poland, and it was at this point—when, as Klara Kemp-Welch puts it, “Kantor may have seen [abstraction’s] oppositional bankruptcy”—that he turned away from it, working henceforth in ways that commented much more explicitly on the outside world.[3]

Still from White People

courtesy Slovene Cinematheque

With the exception of Jürgen Böttcher’s 1981 film Transformations: Potter’s Bull, the remaining films in this program date to the 1970s and show how artists explored traditional and new artistic forms, often as part of larger, usually group efforts to carve out within their environments—which varied widely across Eastern Europe in terms of restrictiveness or permissiveness—a space where countercultural and socially critical ideas could be exchanged freely. This is perhaps most evident in Vladimir Havrilla’s 1976 short film Drawings, in which a traditionally solitary artistic activity is turned into an imaginative form of group communication. Shot in a private apartment in post-1968 Czechoslovakia, moreover, Drawings shows how making a film could turn a small-scale, intimate event into a contribution to the intellectual life of the alternative public sphere. The film is also an important historical document in that it shows how artists could express obliquely—and all the more poignantly for that—aspirations and ideas that they could not express directly without fearing persecution. The same two facets of amateur filmmaking by artists—turning a routine activity into a self-conscious event and expressing criticism obliquely through symbolically charged actions—can clearly be seen in The Hands and Boxing, two 1977 short films made by Romanian artists Geta Brătescu and Ion Grigorescu, respectively.

White People (1970) is the most cryptic film in the group—it hints at a plot through a series of tableaus but keeps the details of a possible story tantalizingly vague. Yet both its loosely connected scenes of hippie free love and rituals and the history of its creation by members of the Slovene OHO collective suggest that the film was an artistic experiment in visualizing countercultural ideals by a group of people who also tried to live those ideals out in real life. A somewhat similar example of an ambitious film project that helped an alternative community come together can be found in the films directed by the Czech dissident Čaroděj OZ, with the notable difference that in more liberal Yugoslavia, White People could still be produced in 1969 at the experimental Neoplanta Studio while in post-normalization Czechoslovakia, OZ’s films were made entirely using personal resources.

Still from Puppets, courtesy Filmoteka Muzeum

Far less cryptic yet also related to art that explores new forms and new social functions are two films made in 1971 and 1975 by Piotr Andrejew, a filmmaker with a background in art history (much like Helena Włodarczyk). In Poland, the most politically liberal of the Warsaw Pact countries in the 1970s, both films were shot with the resources of state film institutions and both received awards. They capture the activities and philosophy of the members of a community of artists that formed at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts around Oskar Hansen, an architect whose theory of Open Form, as David Crowley writes, “argued for spatial forms which were incomplete and, by their incompleteness, required the creativity or participation of viewers or users. . . . In engaging their audiences/users, open forms,” as conceived by Hansen, “had the potential to remind audiences of the fact of their own embodied being. They would also make the individual more attuned to the ordinary [and were] fundamentally a social and decentered conception of space and creativity."[4]

Hansen’s ideas continue to inspire Polish artists to this day;[5] Andrejew’s earlier film Puppets (Pajace, whose title can also be translated as Buffoons) shows how they were taken up in the work of one of Hansen’s students, the artist Paweł Freisler. Freisler is shown making paper dolls out of his photographic self-portraits and then selling them directly on the street, facilitating both the manipulation and the alteration of these playful objects by their owners (the dolls have movable arms and legs) and also embracing unpredictable interactions with his accidental public. During his short artistic career, Freisler’s commitment to art as a mode of direct social interaction was so strong that he largely avoided documenting his activities, making Puppets, a beautiful but more conventional documentary, especially valuable as a record of Freisler’s radical ideas.[6] By contrast, Groping One’s Way (Po omacku), which Andrejew made four years later, is also remarkable as an experimental film in its own right since it tries to convey the spirit of Open Form while capturing a series of exercises that Hansen and his students performed outdoors in order to awaken their senses to the possibilities of artistic creation in any space. To give its viewers a sense of both the communal nature of this endeavor and the multiple possible ways of perceiving it, the film alternates between shots made from a distance and those made from participants’ points of view. Andrejew also alternates between color and high-contrast black-and-white film, unusual sound and discursive speech, and shows events happening at different speeds, with the film mimicking at one point the slow pace of motion of blindfolded participants who are literally groping their way through the exercise. Notably, some of the members of Hansen’s circle of artists from Warsaw, such as the KwieKulik Group, were not only subjects of films but made films themselves, collaborating actively with the Workshop of the Film Form at the Film School in Łódź whose members, in turn, were interested in film as a form of conceptual art rather than a vehicle for storytelling.[7]

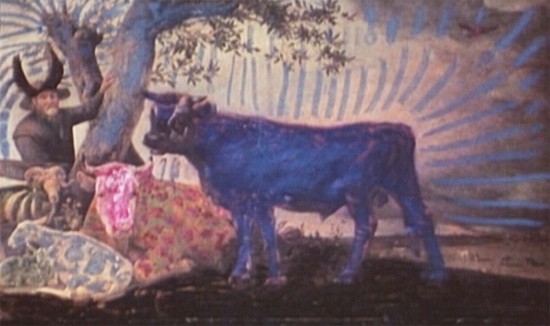

Still from Transformations: Potter's Bull, courtesy DEFA Film Library at the University of Massachusetts Amherst

The final film of the screening also comes from an artist, Jürgen Böttcher, whose career was split between painting (which he did in private due to the persistence of socialist realist dogma in East Germany) and filmmaking, which he did professionally as a director of documentary films at East Germany’s only film studio, DEFA. Transformations: Potter’s Bull is the first part of a poetic three-part film that combines Böttcher’s two artistic passions. In the film, Böttcher paints over postcards of a pastoral Dutch masterpiece, creating a variety of wild new possibilities for the previously placid scene and showing the process of transformation. Boettcher also projects his new creations onto people and objects, as if to suggest that the possibilities for change that his film imagines for art should be projected into real life. Shockingly, despite its lack of even remotely overt political content, the film—the only experimental work ever to be made at DEFA—elicited unease from the censors, proving that the more repressive the political regime, the smaller the artistic gesture needed for an artist’s work to acquire a deep political significance. The possibility—which came with its own frisson—that a work of art intended to be inward-looking, abstract, esoteric, or meditative might become politicized at any moment remained, to varying degrees, a reality for artists around Eastern Europe until the end of the socialist era, when a new set of challenges associated with dramatic economic and social change came to replace the old.

— Ksenya Gurshtein

1. Pawłowski’s film, based on an ephemeral performance, brings to mind other experimental multimedia or intermedia works, most of them abstract, which included projections but were not recorded for posterity. Such multimedia experiments present great challenges when it comes to preservation and re-performance precisely because they were made to exceed the limitations of familiar artistic venues and formats. In the exhibition catalog Sounding the Body Electric, David Crowley offers information about a number of such projects in the former Eastern Europe. They include the “son et lumiere spectacles” or “immersive cinema” created by the Prometei (Prometheus) group in the Soviet city of Kazan from the mid-1960s on; the “kinetic artworks for public space” created by the Moscow-based Mir (World) group of artists, engineers, and composers whose works were displayed “during the jubilee celebrations organized in the Soviet Union in 1967”; and the “kinetic sculptures commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution” that the Dvizhenie (Movement) group, also from Moscow, was invited by officials to create in 1967. The last consisted of “an electric tribute to Lenin in Leningrad. Four enormous screens were placed around the monument to the Bolshevik leader outside the Finland Station. . . . Historic film footage as well as Soviet movies dramatising the revolution were projected onto three screens whilst three beams of colour brought a suggestion of movement to Lenin’s looming silhouette on the fourth. A sound collage of music, poems and Lenin's speeches filled the air.” David Crowley and Daniel Muzyczuk, Sounding the Body Electric, exh. cat. (Łódź, 2012), 23, 25, 27, 33. A phenomenon even more closely related to Pawłowski’s light and sound spectacles filmed in Cinéforms are the works of Milan Dobeš, who worked Slovakia and pioneered kinetic and light-based art in the 1960s. Yet more related examples can be found in the “luminoplastics” of the Croatian artist Aleksandar Srnec, who in the late 1960s made kinetic light-filled sculptures that used projected light. On at least one occasion, in 1972, Srnec created with collaborators (a musician, architect, curator, actor, and the cameraman Vladimir Petek [LINK]) a Proposal for a Lenin Monument in Belgrade, which was meant to be a multimedia installation in public space but was never realized. Crowley and Muzyczuk, Sounding the Body Electric, 190. (back to top)

2. Jarosław Suchan and Marek Świca, eds., Tadeusz Kantor: Interior of Imagination (Warsaw, 2005), 54. Kantor’s writings about his art, as well as information about the full scope of his creative activities, can be found on the site of the Cricoteka. [http://www.cricoteka.pl/en/main.php?d=plastyka&kat=20] (back to top)

3. Klara Kemp-Welch, Antipolitics in Central European Art (London, 2014), 19. For an extensive discussion of the way abstraction in Polish art was or could be interpreted through a political lens, see also Piotr Piotrowski, In the Shadow of Yalta: Art and the Avant-Garde in Eastern Europe, 1945–1989 (London, 2009). (back to top)

4. David Crowley and Daniel Muzyczuk, Sounding the Body Electric, exh. cat. (Łódź, 2012), 57. (back to top)

5. Hansen’s student Grzegorz Kowalski also became a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, where his students include such prominent contemporary Polish artists as Paweł Althamer, Katarzyna Kozyra, and Artur Żmijewski in whose intermedia and socially oriented artistic practice one can see the influence of the ideas of Open Form. (back to top)

6. Łukasz Ronduda, Polish Art of the 70s (Warsaw, 2009), 39. (back to top)

7. Hansen himself also worked across media. He “had close contacts and professional relations with composers and musicians,” proposed designs for built spaces that incorporated sound as part of the experience of the space, and participated in “audio-visual performances.” David Crowley and Daniel Muzyczuk, Sounding the Body Electric, exh. cat. (Łódź, 2012), 57. (back to top)