Radek Pilař (1931–1993), a graduate of the Prague Academy of Fine Arts, earned public recognition above all as the creator of several animated television series for children, a children’s book illustrator, and one of the leading early proponents of Czech and international video art. Pilař first became interested in filmmaking in the early 1960s. His first work was Pin Up (1961), and in it, he used a special animation technique that destroyed his source material in the process of making the film. Pilař poured liquid on stacked and layered photographs taken from popular fashion magazines and shot the images as they gradually blended together. The film foreshadows Dalibor Martinis’ video experiment in Croatia 22 years later when he made Image is Virus. If Martinis’ work is a comment on the consumption of interchangeable images in the popular culture of the present moment, however, Pilař’s work stems from an interest in the imagery of the past. He was fascinated by old photographs and old objects that had lost their original function but could acquire a new existence—for instance, as a part of a work of art. This theme runs throughout Pilař’s amateur film experiments, video art, and even some of the films he made as a professional animator and which were not intended for children, such as Little Shoe (Botička, 1988).

Banner images L to R: Image is Virus, courtesy Dalibor Martinis; Checkmate and Painted in the Air, both courtesy NFD

Painted in the Air (Malování do vzduchu)

Radek Pilař, Czech Republic, 1965, digital file from 16 mm, 3 minutes

Still from Painted in the Air, courtesy NFA

In 1963, inspired by the multimedia projects that he saw at that year’s Biennale de Paris, Pilař began making amateur films more actively, using a 16 mm camera—the only technology available to him. In these private film experiments, Pilař continued to explore the artistic potential of old found footage that was destined for destruction or disappearance. He worked painstakingly to manually cut and splice pieces of different film together, additionally applying paint and scratching the emulsion to alter the images. Working in this way, he created more modest Czech parallels to a significant body of avant-garde handmade and hand-painted cinema by the likes of Stan Brackhage. While Brackhage eventually achieved international renown and influence, however, Pilař’s film work was known only to a handful of his closest friends. In the late 1980s, Pilař became a more public figure as a member and leading proponent on the emerging Czech video art scene. According to Bohdana Kerbachová, “Video art represented a major shift forward in Radek Pilař’s artistic expression. . . . The desire to formulate existential ideas in a succinct way began to push aside the decorative quality that had been typical of his work until then.” In his later works, however, Pilař’s “characteristic poetic quality and idyllic, predominantly positive view of the world gradually faded. . . . In his later video, Pilař progressively abandoned his playful approach, and his child-like spontaneity and playfulness also faded away. His work began manifesting the burden of experience, disillusion and a bitter overtone."[1]

Still from Painted in the Air, courtesy NFD

The short amateur film Painting in the Air (1965) belongs to the period of Pilař’s early experiments and showcases its optimism. It playfully combines home movie–style antics performed for the camera by the Czech poet Václav Fischer and his children with hand-colored abstract forms with which the humans seem to interact. Radek Pilař later succeeded in transferring this film, along with two others from the 1960s (Pin Up and Colors), into his video art works of the 1980s. — Jiří Horníček

With thanks from the series organizers to Dr. Michal Bregant, Jiří Horníček, Daniel Vadocký, and Tomáš Žůrek at the National Film Archive (Národní Filmový Archiv) in Prague for their assistance with research and help in making a screening of this film possible in Washington.

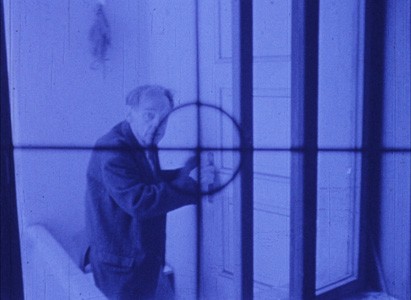

Checkmate (Mat)

Pavel Bárta, Czech Republic, 1983, digital file from 16 mm, 16 minutes 30 seconds

Still from Checkmate, courtesy NFD

Pavel Bárta (b. 1947) inherited a passion for film from his father, Hanuš Bárta, who made silent movies as both a director and an actor in the 1920s under the pseudonym Jan Bondy. His son, Pavel, first started filming with 9.5 mm and 8 mm gauge cameras but since the late 1970s has worked with a 16 mm format. At that time, he became a prominent figure on the independent film scene in Prague, where he lived and worked as a watchman. The small screening room that he created in his apartment was a popular meeting place for young amateur filmmakers who wanted to explore film alternatives to both the commercial and the propagandistic productions that dominated Czech cinema at the time. The small but dedicated group of such like-minded collaborators included, in addition to Bárta, Zdeněk Lorenz (writer, director), Jiří Vaněk (sound recordist, editor), Jiří Vašků, and Michal Hýbek (cameramen).

Most of Bárta’s films speak in allegories and explore situations in which people are exposed to both external pressure and internal doubts. Checkmate addresses these themes through a minimalist and abstract storyline that follows the course of a mysterious visit to an old, crumbling apartment building. Viewers move together with the visitor, thanks to the subjective point of view of a camera that sees what the visitor sees. The sense of the camera’s subjective and menacing perception is emphasized, moreover, through the crosshairs of a gun sight that hovers in front of every shot, as well as through the stylized color toning of the black-and-white film. As the visitor moves through the building, its individual tenants are caught—imprisoned—in the viewfinder of the camera while the intruder forces them to repeat incomprehensible words (gibberish in Czech as much as English) after him. Unnoticed, a little boy observes everything from a distance. Throughout the film, the sequences of subjective camera shots are interrupted by colorful collages of photos from contemporary magazines and shots of the ramshackle house. Though Bárta himself has not addressed this point, the film’s visual sensibility looks as though it could have been inspired by British pop art.

Still from Checkmate, courtesy NFD

It would be too easy and simplistic to interpret Bárta’s films as merely reflections of the social atmosphere of Communist Czechoslovakia in 1980s, although he did have personal experience with state repression and surveillance by state security agencies, which “followed” his filmmaking. Looking beyond his immediate environment, however, Bárta’s films also address the anxiety, uncertainty, and loneliness that haunt people regardless of the social system in which they live. Even viewers with no knowledge of Checkmate’s political background can respond to Bárta’s unconventional narrative and experimental technique and might take Bárta’s enigmatic creation in the spirit of his own assertion that, “a film for me is like an unreachable infinity; the further I go into it, the larger the spaces that appear in front of me."[2] — Jiří Horníček

A longer text by Jiří Horníček on Bárta and his work is available online in Czech.

With thanks from the series organizers to Dr. Michal Bregant, Jiří Horníček, Daniel Vadocký, and Tomáš Žůrek at the National Film Archive (Národní Filmový Archiv) in Prague for their assistance with research and help in making a screening of this film possible in Washington.

1. Bohdana Kerbachová, “Images in Time—the Video Art of Radek Pilař,” in Radek Pilař (Prague, 2003). (back to top)

2. “Kdo je kdo . . . Pavel Bárta,” Amatérský film a video [Amateur film and video] 20, no. 3 (1988): 55. (back to top)