Eco’s career as a semiotician formally began with the publication of The Absent Structure in 1968, but his previous writings on aesthetics and textual interpretation informed his theories. Of the work that emerged out of this prior academic period, The Open Work is undoubtedly the seminal text.

Ipersignificato

Ipersignificato: Umberto Eco and Film

L’Avventura, Stagecoach, and Casablanca

Still from L’Avventura, courtesy Janus Films/Photofest.

"If everything seems so casual, it is precisely because nothing is."— Umberto Eco, The Open Work [12]

Originally appearing in 1962, Opera Aperta underwent various revisions and editions and, in the process, became central to “the continuing contemporary debate on literature, art, and culture in general,” as the introduction to the 1989 edition underlines [13]. The interpretative potential of a work of art becomes the basis for Eco’s theory, which attempts to distinguish between tradition and modernity, convention and ambiguity, and to identify true innovation in works of art as a form of “openness.”

Still from L’Avventura, courtesy Janus Films/Photofest.

In terms of its cinematic articulation, Eco discusses the role of the moving image with reference to a principal dichotomy; on one end are works of utter innovation attained through ambiguity, and at the other end are works that achieve a completeness within a closed system of interpretation. Every work of art, Eco notes, has a degree of openness determined by the nature of an audience. However, works that also have openness built into their structure inhabit a different category altogether, and invite a participation from the audience that is essential to their completion. The particular brand of openness seen in Michelangelo Antonioni’s films illustrates a crucial chapter of The Open Work [14]. Eco often referenced and observed Antonioni’s output in his writing, and here the director’s early work provides an example that Eco sees as distinguishing him from most of his peers. L’Avventura (1960) in particular, which Eco presents as a central example of formal deconstruction in film, holds a pivotal role for the sudden shift it brought to the syntax of cinematic language, perhaps even more so because such a shift was accepted, at least in part, by a general viewing public [15]. In line with the schism portrayed between classical and experimental art, and placed alongside such works as the music of Karlheinz Stockhausen and James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, L’Avventura’s openness relies on a special kind of organization, Eco argues, whereby conventional narrative is either subverted or rejected in lieu of spatial and temporal voids. In translating the psychological alienation of his characters into a formal alienation, Antonioni enacts a “decantation of the dramatic action” where the appearance of randomness and chance, suggested by a lack of strict causality in the film’s movements, veils a carefully willed tracing of unresolved expectations [16].

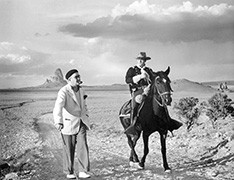

John Ford and Tim Holt on location in Monument Valley, 1939, courtesy United Artists/Photofest.

As a counterpart, Eco refers to the Aristotelian craft of John Ford’s Western Stagecoach (1939). Acknowledging that “the open work is only one expression [. . .] of a culture whose innumerable demands can be satified in many different ways,” Eco points to instances where traditional narrative structures incorporated by contemporary uses are “perfectly valid.” Ford’s film is presented as the embodiment of art that “confirms conventional views of the world” in a culture that was beginning to accommodate the modern work that “implicitly denies them.” [17]

"Works are created by works, texts are created by texts and all together they speak to and with one another independently of the intentions of their authors. A cult movie is the proof that, as litera- ture comes om literature, cinema also comes om cinema."— Umberto Eco, “Casablanca: Cult Movies and Intertextual Collage” [18]

Postmodern culture has a fundamental self-awareness of

its artistic output, an inwardness of gaze stemming from a need to confront and reiterate the knowledge it possesses. This notion of cultural repetition characterizes a large part of Eco’s theories in the late twentieth century, when much of his writing turned to a less theoretical and more informal type of observation. “Innovation and Repetition: Between Modern and Postmodern Aesthetics,” a title from 1985, contains many of the ideas that formed around the aesthetics of seriality, and presents, alongside a host of cinematic references, a process of cultural reiteration that marks a radical departure from the modern idea of art that had distinguished the prior decades [19].

Still from Casablanca, courtesy Warner Brothers.

Reiteration would become synonymous with a large part of contemporary culture as we understand it. Eco, however, stresses the fact that this seriality, in a broader sense, has firm roots in the eternal archetypes that shape our approach to storytelling. A sense of heightened intertextuality, then, informs the writer’s analysis of Michael Curtiz’s classic, Casablanca (1941), and its lasting, universal success. What distinguishes Curtiz’s film from the postmodern aesthetics Eco describes, however, and what makes it truly of interest, is its lack of self-awareness and structure, which suggests no irony in its application of previous tropes. Crucially, it predates the era

of meta-cinematic quotation. In a series of essays dedicated to the cult status of the film, Eco credits its embodiment of a full range of known and established topoi as the foundation for the prolonged and intense appeal the picture continues to generate. Though careful not to praise it as a particular aesthetic achievement, Eco presents Casablanca as the rare phenomenon whereby the world created by the film — a world of collaged existing ideas — becomes greater than the artifact itself, a synthesis of a collective imagination which recognizes itself in the images and relationships portrayed and canonizes them in the process. As a result, individual threads are elevated into an anthology of drama, rather than any distinct aesthetic vision. Eco is able to call the fim a “hodgepodge

of sensational scenes strung together implausibly” in one moment and “a stroke of genius” in the next precisely because of its composition.

The film’s essence, he would argue, lies outside of the picture itself, within a cult aura generated by the viewing public and the forces which promoted its existence, in spite of its famously disoriented production: “something has spoken in place of the director.” In the trajectory of cinematic language, Eco underlines Casablanca as a historic event, a signifier of an age which holds the truths of what the medium would eventually evolve into, and, simultaneously, “a dance of eternal myths” that came to the surface free from authorial intention and, much like Fellini, the external. This alone, according to Eco, is “a phenomenon worthy of awe" [20].

—Umberto Varricchio

Previous: Amarcord and Teorema

[12] Umberto Eco, The Open Work (Cambridge, MA, 1989), 117. (back to top)

[13] David Robey, introduction to The Open Work, viii. (back to top)

[14] Eco, The Open Work, 115 – 121. (back to top)

[15] Eco, The Open Work, 115 – 121. (back to top)

[16] Eco, The Open Work, 115 – 121. (back to top)

[17] Robey, xi. (back to top)

[18] Umberto Eco, “Casablanca: Cult Movies and Intertextual Collage,”

SubStance 14, no. 2, issue 47 (1985): 4. (back to top)

[19] Umberto Eco, “Innovation and Repetition: Between Modern and

Postmodern Aesthetics,” Daedalus 114, no. 4 (Fall 1985): 161 – 184. (back to top)

[20] Umberto Eco, “Casablanca, or, the Cliches Are Having a Ball,” in

Signs of Life in the U.S.A.: Readings on Popular Culture for Writers, ed. Sonia Maasik and Jack Solomon (Boston, 1994), 260 – 264.

The National Gallery of Art’s film program provides many opportunities throughout the year to view classic and contemporary cinema from around the world.

View the current schedule here.