In the Library: Deforming and Adorning with Annotations and Marginalia

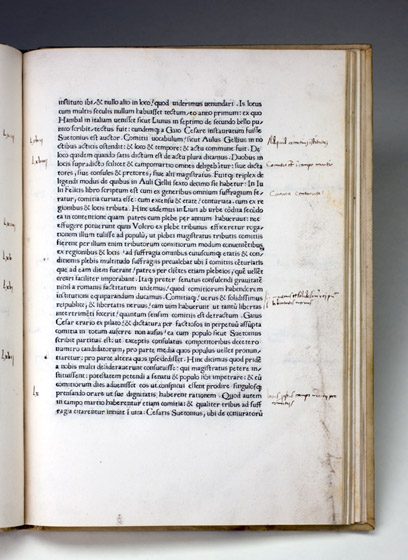

Biondo Flavio, 1392–1463Blondi Flavii Forliviensis in Roma instaurata prefatio incipitRome, before July 26, 1471

National Gallery of Art Library, The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation

Early printed books did not have the design conventions we are familiar with today. An index or table of contents was only rarely included, and often the text was not divided into chapters or even set in paragraphs, as in this book describing the ancient ruins in Rome. To help navigate the page’s contents without needing to read the entire block of uninterrupted text, an early owner added annotations in the margins, noting references to particular buildings and sites. Marginalia like these probably influenced the development of page design.

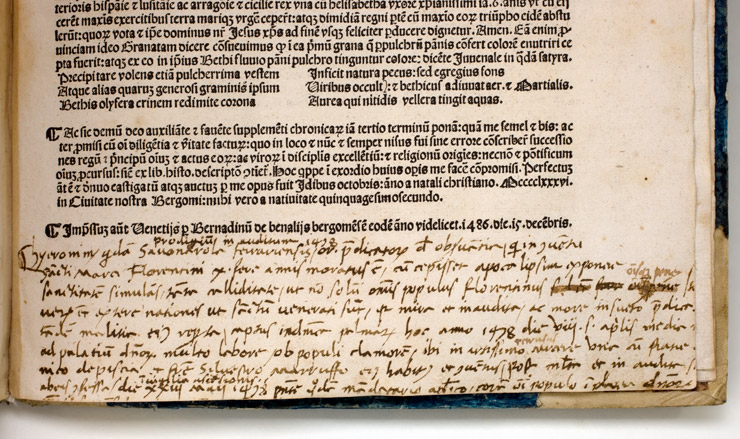

Jacobus Philippus, Bergomensis, born 1434Fratris Iacobi Philippi Bergomensis, Ordinis Fratru[m] Eremitarum Diui Augustini, In omnimoda historia nouissime congesta, Supplementum cronicaru[m] appellataVenice, December 15, 1486

National Gallery of Art Library, The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation

This chronicle of world history was owned by the painter Agnolo Bronzino (1503–1572). In addition to signing his name on the first leaf of text, Bronzino created a unique copy of the edition by marking annotations throughout and updating it on the last leaf with a description of the trial and execution of the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola, events which occurred after the book's publication.

LivyT. Livii Patavini Latinae historiae principis Decades tres cum dimidiaeBasel, 1549

National Gallery of Art Library, C. Wesley and Jacqueline Peebles Fund

The Library’s copy of the 1549 edition of Livy's Roman history contains marginal annotations in three hands. Most notable are the drawings that accompany the first 60 pages of text and enliven the dense, scholarly work. These small scenes in two colors of ink were likely sketched by Nicholas Udall (1505–1556), an English scholar, schoolmaster, and playwright known for his play Ralph Roister Doister, considered the first comedy in the English language.

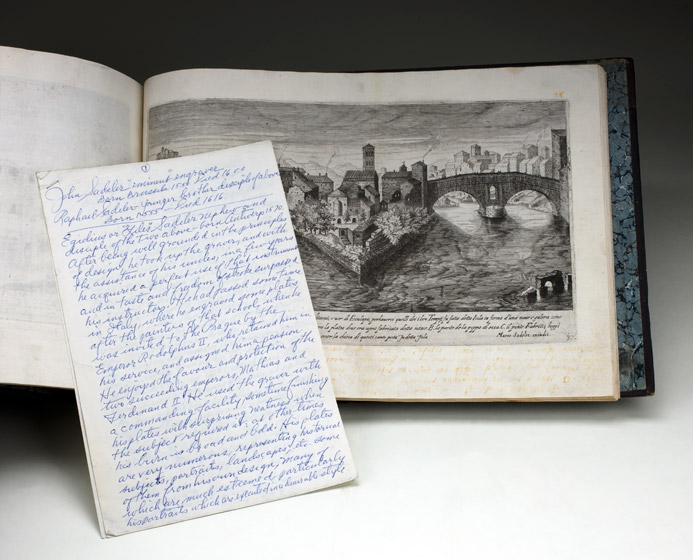

Hieronymus Cock, born c. 1510Scenographiae, sive perspectivae . . . pulcherrimae viginti selectissimarum fabricarumAntwerp, 1560

National Gallery of Art Library, J. Paul Getty Fund in honor of Franklin Murphy

Based on the drawings of Hans Vredeman de Vries (1527–c. 1606), this suite of fantastic architectural engravings was intended as a pattern book for artists (this particular copy did, in fact, belong to a family of artists). It is signed on the title page by Ioannes and Philips Vingboons, engravers active in Antwerp in the 17th century; the brothers used the margins and blank versos to sketch ideas (as well as to clean their brushes).

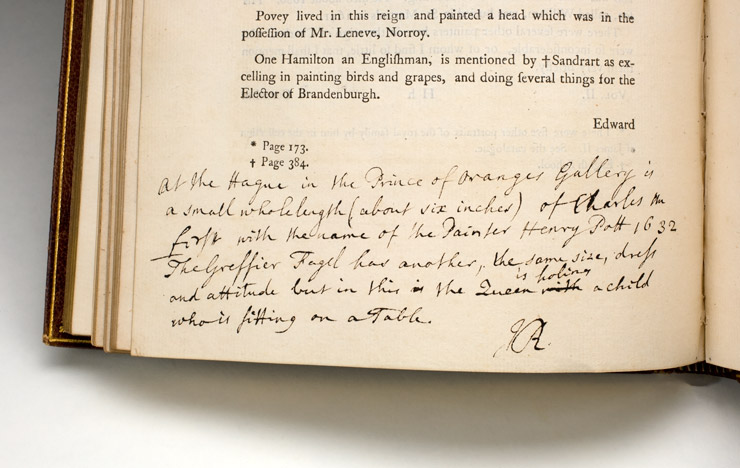

Horace Walpole, 1717–1797Anecdotes of Painting in EnglandStrawberry Hill, 1762–1771

National Gallery of Art Library, Gift of Joseph E. Widener

The remarks throughout this four-volume set reveal that this copy of an important 18th-century work on British paintings once belonged to Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792). His commentary illuminates his relationship with the author and his role as the head of the Royal Academy of Arts.

Giles Sadeler, 1570–1629Vestigi delle antichita di Roma, Tivoli, Pozzvolo et altri lvochiPrague, 1606

National Gallery of Art Library, C. Wesley and Jacqueline Peebles Fund

In addition to the captions below each plate, now faded, this book of engravings of ancient Roman architecture and sculpture came to the Library with several pages of handwritten notes prepared by a previous owner. These notes provide details about the Flemish engraver who designed the plates.

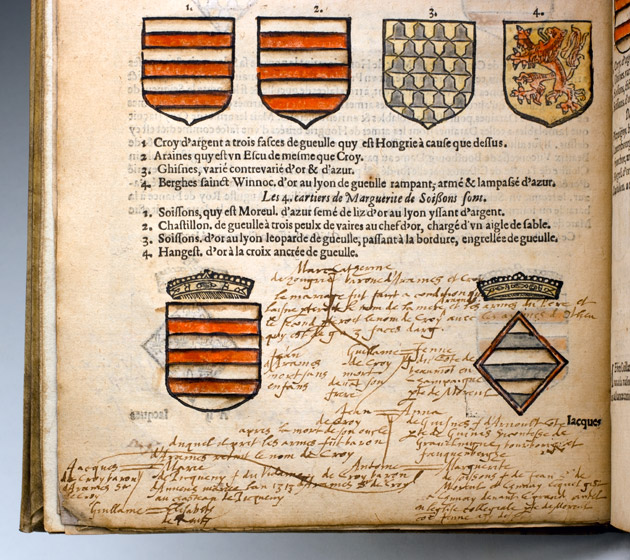

Jean ScohierGenealogie et descente, de la tres-illustre maison de Croy. Par m. Iean Scohier beaumontoisDouay, 1589

National Gallery of Art Library, David K. E. Bruce Fund

This book of genealogy is annotated throughout with supplemental information about the Croy family, who were nobles in Belgium. A previous owner has also greatly enhanced the book by providing colors for many of the coats of arms. As the coloring is incomplete and inconsistently applied, it is likely unique to this individual copy.

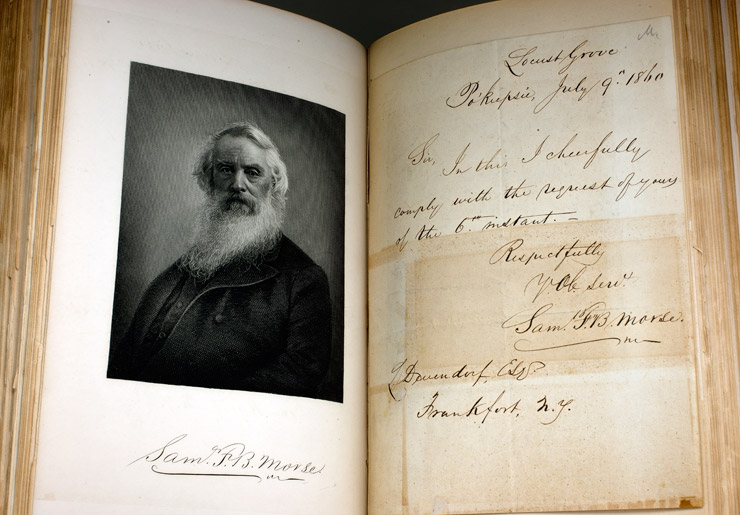

Henry Theodore Tuckerman, 1813–1871Book of the Artists: American Artist Life

New York, 1867

National Gallery of Art Library, David K. E. Bruce Fund

The Library owns three copies of this important work on 19th-century American artists. Two contain significant additions to the standard version. The first is a special version containing 49 photographs of artists who were still alive in the 1860s, with 43 of them signed by the artists themselves. The second, shown here, is bound in two volumes with extra pages for mounting 30 autographed letters from the artists and 122 additional plates showing reproductions of the artists' works and engraved portraits.

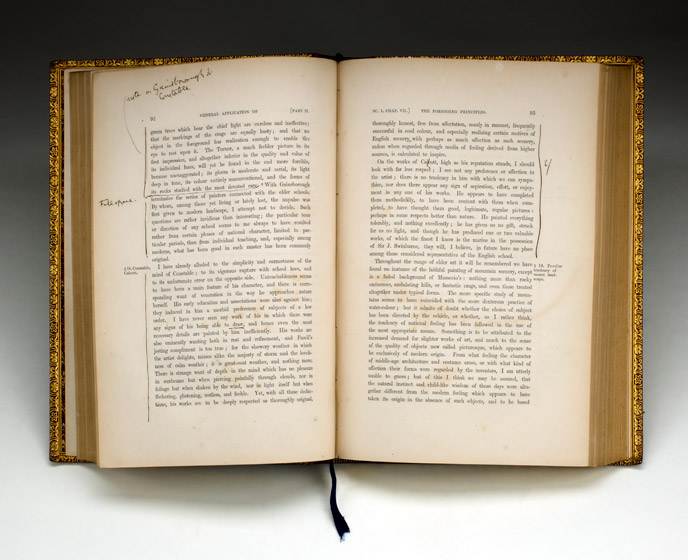

John Ruskin, 1819–1900Modern PaintersLondon, 1846–1860

National Gallery of Art Library, Gift of Paul Mellon

This set of John Ruskin's Modern Painters, which belonged to the author himself, comprises volumes from various editions. Ruskin made notes throughout in preparation for a new edition, with several significant changes of both content and structure. Most compelling are his additions regarding the Pre-Raphaelites (a group of artists that included William Holman Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and John Everett Millais), who had not yet formed their famous brotherhood when the first volume of Ruskin's work appeared in 1846. Nonetheless, this work did influence them, and Ruskin became one of their most important supporters, devoting more and more space to promoting their ideals in subsequent editions.

John Rewald, 1912–1994Cézanne et ZolaParis, 1936

National Gallery of Art Library, David K. E. Bruce Fund

The John Rewald collection is a veritable treasure trove for bibliophiles interested in marginalia. Rewald’s significant holdings came to the Library after his death. The art historian annotated many of the books in his collection quite heavily, and none more than his own. This is a personal copy of his doctoral dissertation, completed at the Sorbonne, which he had bound with extra pages for notes and correspondence. Rewald continued to work on the project throughout his life, never considering it complete; much of the extra material was never published.