Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World

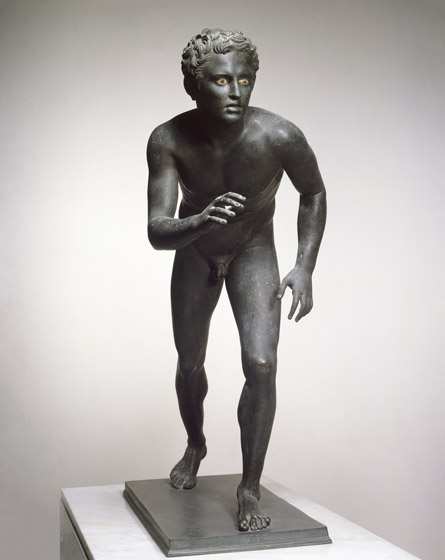

Victorious Athlete ("The Getty Bronze") 300 - 100 BC; bronze and copper. Lent by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu.

Italian fisherman recovered this statue from the Adriatic Sea in the 1960s. Commemorating a successful athlete, the figure stands in the conventional pose of a victor: he is about to remove his victory wreath of laurel or olive leaves and dedicate it to the gods in gratitude. His eyes were originally inset and his nipples are inlaid in copper, which would have appeared red in contrast to the once golden brown color of his bronze flesh.

Alexander on Horseback, 100 - 1 BC; bronze, copper, and silver. Lent by the The National Archaeological Museum, Naples (MANN).

The Macedonian king wears a royal diadem in his wavy hair, and a short cloak (chlamys), cuirass, and laced military sandals. He once brandished a sword in one hand, while the other grasped the reins of his rearing horse, presumably his favorite, Bucephalus (Bull Head). Found in 1761 in Herculaneum in Italy, the statuette is thought to be a small-scale replica of a lost monumental sculpture that Lysippos created in celebration of Alexander's victory over the Persians in 334 BC.

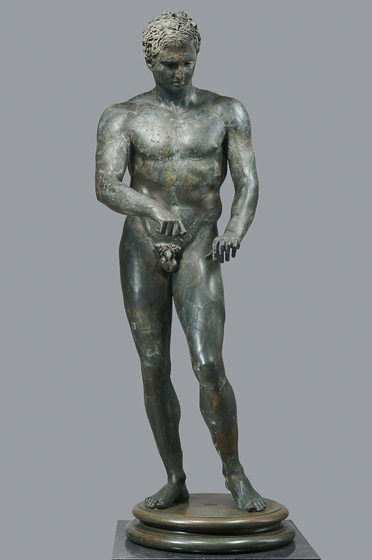

Youth ("Idolino), c. 30 BC; bronze, copper, and lead. Lent by Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Firenze).

Portrait of Aule Meteli ("The Orator"), 125 - 100 BC; bronze and copper. Lent by Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Firenze).

The gesture of Aule Meteli's upraised hand, interpreted as a request for silence before starting a public speech, demonstrated the ability of bronze -- stronger and lighter than marble -- to render dynamic poses without support. The figure wears a Roman toga, with a red copper stripe on his tunic, but the inscription that names him on the border of his garment is written in the language of the Etruscans. An ancient people in the region of present-day Tuscany and Umbria, the Etruscans had close ties to Greece and Greek colonies in southern Italy and were eventually assimilated into the Roman Republic.

Portrait of a North African Man, c. 300 - 150 BC; bronze, copper, enamel, and bone. Lent by the Trustees of the British Museum, London.

Excavated in 1861 near the Temple of Apollo at Cyrene along with fragments of a gilt-bronze horse, this head represents an indigenous Libyan or Berber. High cheekbones, crow's-feet at the eyes, and a short beard contribute to the portrait's realism and indicate the interest of Hellenistic sculptors in accurately portraying foreign peoples. The lips, inset with copper (now tarnished), are parted slightly to reveal bone teeth; the inlaid eyes, outlined with copper lashes, preserve traces of white enamel.

Portrait of Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus Pontifex, 15 BC - AD 15; bronze. Lent by the National Archeological Museum, Naples (MANN).

The brother-in-law of Julius Caesar, Piso Pontifex (48 BC - AD 32) was a highly cultured member of the Roman elite (the ancient poet Horace dedicated a treatise to him). He was also the son of the reputed owner of the luxurious Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum, destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 but famous for its collection of bronze and marble sculptures excavated in the 1750s. This likeness harks back to portraiture of the Roman Republic that embodied the virtues of severitas (strictness) and gravitas (dignity), but its expressive power is distinctive of Hellenistic sculpture.

Portrait of a Man, c. 100 BC; bronze, copper, glass, and stone. Lent by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, Education, and Religious Affairs, The National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

This highly individualized likeness epitomizes the realism that Greek artists achieved in the Hellenistic period. Once part of a full-length statue, the head turns slightly to one side, enhancing the pathos of the man's concerned expression. Both inserted eyes are preserved, giving a vivid impression of the original appearance of portraits that have lost them. The man's identity is unknown, but such details as the soft, rolling flesh, furrowed brow, and crow's-feet leave no doubt that this sculpture represents a specific individual. The original statue was likely an honorific portrait of a citizen displayed in the palaistra, a training ground for athletes, where this head was found on the Greek island of Delos in 1912.

Portrait of a Boy, 100 - 50 BC; bronze and copper. Lent by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, Education, and Religious Affairs, The Archaeological Museum of Herakleion.

Wearing a long cloak that envelops both arms and hands, and elaborate sandals, this figure was discovered in 1958 along the beach of Hierapetra on the Greek island of Crete. The boy's sober, almost melancholy expression, corresponds with his solemn, dignified pose. Executed fully in the round, the stuatue may come from a funerary monument.

Portrait of a Poet ("Arundel Head"), c. 200 - 1 BC; bronze and copper. Lent by the Trustees of the British Museum, London.

Discovered in the 1620s at Smyrna (Now Izmir, Turkey), this arresting portrait of an elderly man embodies Hellenistic style in the realism of the wrinkled face, the interest in characterizing old age, and the heightened emotional expression perhaps signifying mental concentration. The missing but original downcast eyes could suggest that he was reading a book. The profession of the sitter is indicated by the long hair, full beard, and round fillet on the head--alll attributes of Greek poets, philosophers, and other intellectuals.

Athlete ("Ephesian Apoxyomenos"), 1 - 90 AD; bronze and copper. Lent by the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Antikensammlung.

Boy Runner. 100 BC - AD 79; bronze, bone, and stone. Lent by The National Archeological Museum, Naples (MANN).

The Runner comes from the Villa dei Papiri, the largest and most lavish of the seaside villas built around the Bay of Naples for wealthy Romans. Buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79, the villa was partially excavated in the 1750s when this sculpture, one of a pair, was found near a 218-foot swimming pool in a colonnaded garden. Poised for action, the runner is about to launch into a foot-race or stadion, from which the word "stadium" derives. The stadion was the oldest of the Olympic games, which celebrated individual prowess rather than team sports. The figure dramatically illustrates the dynamic poses made possible by the tensile strength of bronze.

Weary Herakles, AD 1 - 100; bronze, copper, and silver. Lent by the Museo Archeologico Nazionale dell' Abruzzo, Villa Frigerj, Chieti.

Based on a famous lost statue by Lysippos, this extremely fine statuette portrays Herakles weary after completing one of his final labors. He originally held behind his back the golden apples of the Hesperides, which gaurunteed his immortality. The inscription around the base states that the sculpture was dedicated to Herakles by a merchant engaged in trade in the eastern Mediterranean. The sculpture was excavated in 1959 at a shrine devoted to the god at Sulmona, Italy.

Athena ("Minerva of Arezzo"), 300 - 270 BC; bronze and copper. Lent by the Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Firenze).

The goddess of war and wisdom wears a protective garment (aegis) with the head of a Gorgon, a mythical female monster whose powerful gaze was fatal to any onlooker. Athena's lips are plated with copper and her eyes were originally inlaid to give a lifelike appearance. She probably once held a spear in her right hand. The sculpture was discovered in fragments in the remains of an ancient house at Arezzo in 1541. The gray epoxy-resin fills were added in a recent conservation treatment.

Medallion with Athena and Medusa, 200 - 150 BC; bronze and glass. Lent by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, Education, and Religious Affairs, The Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki.

With holes for attachment, this bronze disk probably adorned an elaborate chariot. The goddess Athena raises her right arm to throw a spear, the sense of her movement conveyed by feathers that seem to ruffle in the breeze and curling locks whipped by wind. Her helmet is composed of the head of the Gorgon Medusa, whose glance turned one to stone. The monsters placid face, with eyes closed in death, contrasts with the alert expression of the goddess. The medallion was found in 1990 among the ruins of an ancient building in Thessalonik, perhaps a Macedonian royal palace.

Sleeping Eros, 300 - 100 BC; bronze (with a modern marble base). Lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund.

Before the Hellinistic period, children were typically portrayed as miniature adults. Here Eros, god of love and son of Aphrodite, is depicted in the form of a sleeping baby. Draped limply over a rock, the infant Eros provided the perfect subject for the artistic exploration of a child's body at rest. His bow (cast separately and now missing) has just fallen from his right hand, which hangs down across his chest, fingers relaxed in slumber. The original base was most likely of stone, adding to the sculpture's realistic impression.

Dancing Faun (Pan), c. 125 - 100 BC; bronze and silver. Lent by The National Archeological Museum, Naples (MANN).

This exuberant dancer once adorned the atrium of the House of the Faun, which was named for this sculpture and was so large that it filled an entire city block in Pompeii. The statuette's aging face, lascivious grin, and goat's horns suggest that it represents not just any faun (or satyr), but the rustic god Pan himself. A lustful musician and deity of shepherds, Pan also caused inexplicable fear, or panic, in animals and humans. Graceful and unkempt, elegant and grotesque, the figure embodies the Hellenistic aesthetic in its dynamic pose and wild expression.

Apollo ("Pompeii Apollo"), 100 BC - AD 79; bronze, copper, bone, stone, and glass. Lent by the Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni archeologici di Pompeii, Ercolano, e Stabia.

Excavated in a house in Pompeii in 1977, this bronze shares its pose and features with the following slide's Archaic-style statue of Apollo. The two sculptures hark back to the same prototype, but this figure had a different function. While the Piombino Apollo served as a votive offering in a religious sanctuary and probably once held a bow and libation bowl for pouring wine, the Apollo from Pompeii was a lamp-bearer that decorated an elite dining room. It once carried two tendrils to support a tray. Thus the statue not only satisfied the patron's antiquarian interests but also had a useful purpose.

Apollo ("Piombino Apollo"), c. 120 - 100 BC; bronze, copper, and silver. Lent by the Museé du Louvre, Départment des antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaine, Paris.

This statue imitates the schematic hairstyle and rigid stance of Greek sculptures of the sixth century BC, although the limbs are more slender and the hands and feet more naturalistically rendered than is found in genuine Archaic Greek art. The inscription to Athena on the figure's left foot and fragments of a lead tablet found inside the statue suggest that the sculpture was an offering to the goddess at a sanctuary on the Greek island of Rhodes. Later the statue was brought to Italy, where it was recovered from the harbor of Piombino in 1832.

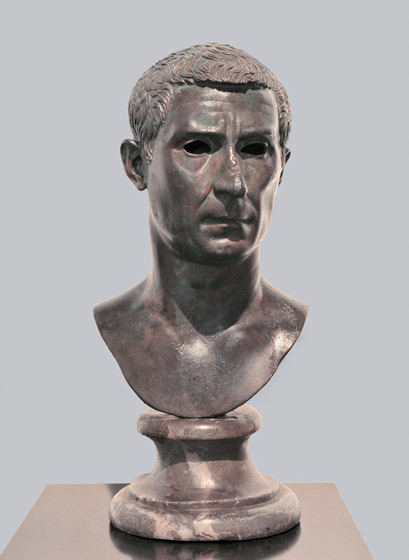

Herm Bust of the Doryphoros, 50 - 1 BC; bronze. Lent by the National Archeological Museum, Naples (MANN).

Inscribed in Greek: "Apollonios, son of Archias, of Athens, made [this]"

The Doryphoros was a famous full-length statue of a heroic spear-bearer created by the fifth-century BC Greek sculptor Polykleitos. This herm bust, which excerpts just the head and chest of that figure, is considered one of the finest surviving replicas, capturing the finely incised hair and idealized facial features of the now-lost original; its eyes are eighteenth-century restorations. The bust was found in 1753 amid the extensive collection of sculpture that decorated the Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum. The artist Apollonios of Athens added his signature in Greek along the front, advertising both his Greek pedigree and his ability to make fine replicas of Classical works.