I have finished drafting the new chapters. The subject of the last chapter, the reception of gardens in poetry and painting, was discussed in part in an essay I published in 2012, but it needs further development. The essay presents the poems of Abdi Bayk Navidi (1515 – 1580) on the garden city created by Shah Tahmasb (1524 – 1576) in Qazvin. The Safavid kings are likened in these poems to the mythical Persian kings Jamshid, Feraydun, and Iskandar. Their tribute to ancient Sasanian rulers is reflected in their Sufism, indebted to the Zoroastrian gestalt absorbed into the Shiite version of Islam, as discussed in the works of Henry Corbin. The king is the shadow of God and the Prophet’s light.

These Sufi ideas were manifested not only in Navidi’s poetry but also in the paintings created in the royal workshops. Navidi praised Shah Tahmasb’s painter Ali Mirak, comparing him to the great Zoroastrian painter Mani. Navidi saw the arts as issuing from the Prime Intelligence: God, the First Painter, has created with his pen the post of light that holds up the tent of the sky.

Navidi explained how Ali Mirak, the court painter, through “licit” magic, reflected the picture of the created world in his heart, as in a mirror, engaging with each created being and presenting a like one. He then recounted a competition, prompted by Alexander the Great, between European and Chinese painters. The latter polished the walls of the loggia of a house for forty days, to the point where it was as reflective as a mirror. Thus when Alexander and his men stepped into the building, they saw not only the image of people of great beauty and magnificence but also the motion of whoever entered. Chinese art was thereby deemed superior since it produced a reflection rather than an imitation of nature.

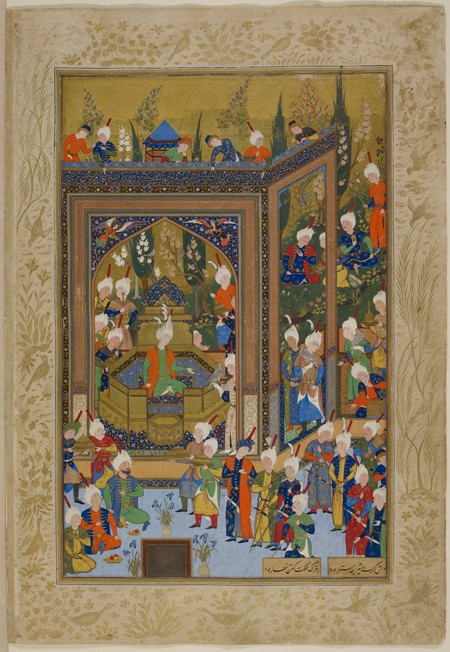

Navidi used this story to point to the mirror as a means of perceiving true reality. To be licit, an image should reach beyond the appearance of things, and the viewer should see beyond the image to what it does not show. The garden of the king contained licit paintings that reflected what is beyond the images; that is, creation itself. Thus we can see in a miniature from Shah Tahmasb’s workshop, The Enthronement of Khusraw, that the royal loggia is depicted as a gilded book of poetry open to the garden. As the king was regarded as the shadow of God on earth, so too was the royal garden seen as a manifestation of the entire created world.

Members' Research Report Archive

Safavid Gardens from a Persian Perspective

Mahvash Alemi, Rome

Ailsa Mellon Bruce Senior Fellow, fall 2013

My research at CASVA focused on Safavid gardens in Iran, which will form part of a book I am writing that is based on the study of examples in different cities. My previous work was devoted mainly to reconstructing the physical features of Safavid garden cities, a necessary task as there were no maps of Persian cities from the Safavid period. By sifting through information from Safavid chronicles and the accounts and drawings of European and Ottoman travelers, I was able to reconstruct a number of Safavid plans of cities relevant to my inquiry. Drawings by Pietro della Valle (1586 – 1652), in the Vatican Library, and by Engelbert Kaempfer (1651 – 1716), in the British Library, together with painted maps by the sixteenth-century Ottoman polymath Nasuh Matrakçi, were the principal visual documents I used to re-create the plans of Safavid capitals (Tabriz, Qazvin, and Isfahan); Caspian shore hunting resorts (Ashraf, Farahabad, and Sari); and smaller towns such as Khuy, Qom, Shiraz, Kirman, and Kashan.

During my fellowship I also finished a reconstructed city plan of Ardabil, the Safavids’ power base, and I identified Persian miniatures to be discussed in the book. The preparation and presentation of my colloquium prompted me to revise the structure of my account and make significant additions. The book, initially designed to present each major city and its gardens in turn, is now reorganized thematically. The first four chapters, which cover, respectively, the history of the Safavids and their gardens, sources of garden diversity, structuring the city, and stimulating pilgrimage, will be followed by chapters on the major garden types (dawlatkhāna and chahārbāgh), as well as other types; elements of garden composition; garden rituals and ritualized practices; and Safavid reception of gardens in poems and paintings.

Artist in the workshop of Shah Tahmasb, Qazvin, The Enthronement of Khusraw, fol. 60v from Nizamī Ganjavi, Khamsa. The British Library, Or. 2265:60v. © British Library Board