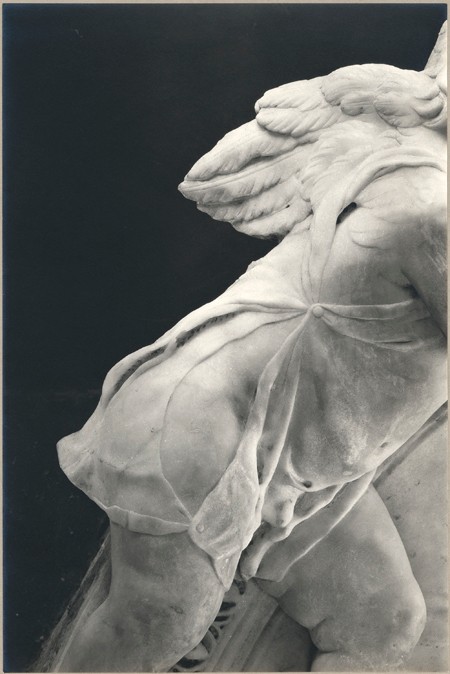

Clarence Kennedy (1892–1972), an art historian who taught at Smith College and a self-proclaimed “scholar-photographer,” revolutionized documentary art photography with his subtle and illuminating details of Italian Renaissance sculpture. The limited photographic resources available for teaching art history, especially sculpture, in the early 1920s led him to pick up the camera himself. After initiating photographic surveys to market to colleges and museums, Kennedy won the attention of the celebrated art dealer Joseph Duveen, leading to a partnership that resulted in projects with collectors such as Helen Frick, Henry Goldman, Clarence Mackay, and Joseph Widener. These associations, as well as his own art-historical studies, led to his most lauded achievement, the seven-volume Studies in the History and Criticism of Sculpture, containing more than three hundred photographs of ancient Greek and Italian Renaissance sculpture, with special attention to Desiderio da Settignano (c. 1429–1464) and the Florentine Quattrocento. His careful consideration of lighting and point of view as well as his inclusion of illuminating details ultimately changed the possibilities for what one could learn from a reproduction. Kennedy’s photos have been criticized for being more beautiful than the originals, but he continually maintained that his work involved “no witchery of the camera”; it only revealed what was already there, showing it unobscured by less than ideal conditions.

Kennedy’s fellow art historians praised his photographs as unprecedented aids for teaching and connoisseurship. In addition, their aesthetic value earned the admiration of respected photographers, especially Ansel Adams (1902–1984), who described Kennedy’s work as revealing “not only his perception of the varied

Kennedy has been the subject of at least forty-five solo exhibitions since 1922. Several were accompanied by brochures or small catalogs of varying levels of scholarship, none with more than five pages of text. They largely focused on his photographs, but how he came to make these iconic images is, along with his other varied pursuits, a largely untapped subject. Kennedy was not only a photographer and a scholar of art history but also a sought-after innovator in stereography, museum installation, typography, printing, and book design. A common theme of these diverse interests was his ambition to achieve the best possible reproduction—whether in flat photos, three-dimensional projected images for teaching, books

Kennedy’s wide-ranging achievements as a scholar, artist, technician, scientist, inventor, and teacher make him a rare and fascinating figure. He made significant contributions to the establishment of art history as a respected field of study in America through the influence not only of his photographs but also of his teaching, both at Smith College and abroad. He and his wife, fellow art historian Ruth Wedgwood Kennedy (1896–1968), cast a long shadow at Smith both as scholars and as the originators of an innovative art history program in Florence and Paris.

My CASVA fellowship has given me the means to examine carefully the two main primary sources for Kennedy’s life: his art-historical research files, in the Harvard Fine Arts Library, and the more personal materials among the Clarence and Ruth Wedgwood Kennedy Papers in the Smith College Archives. These, supplemented with substantial documents from the archives of the Carnegie Corporation and Duveen Brothers as well as the Ansel Adams Papers at the University of Arizona and Stanford University bring Kennedy’s career and personality into focus. With the aid of these