My book explores the foundational moment of pictorial articulation of, and critical thinking about, this important cultural concept. The mid-Ming period (c. 1450–1550) of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) heralded the “silver century” (1550–1650) of a monetary economy in

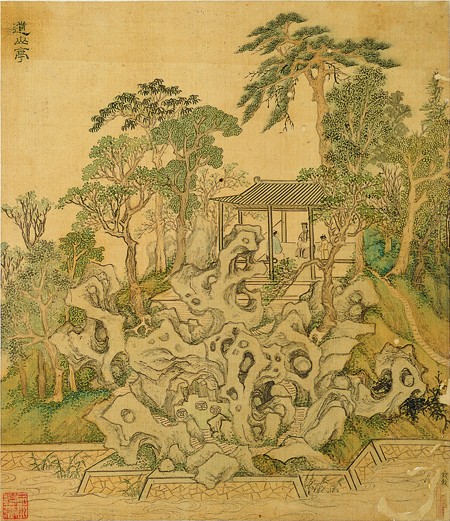

Designers and builders of the mid-Ming period created courtyards, gardens, and public sites by seeing or constructing place through pictorial conceits, and, through a concern for a sense of place, painters ardently correlated their pictorial themes with specific places in their actual surroundings. I argue that these intertwined processes of place-making and picture-making aligned the concept of “real scene” with an ecological aesthetic that acknowledged the visual and material clues and active forces of objects in spaces and afforded bodily and experiential engagement with the environment.

The reassessment of “real scene” practices forces a revision of the conventional view that Chinese ink painting was nonrealist and spontaneous. I argue instead that mid-Ming literati artists showed a determined pursuit of technical mastery and engagement in a prolonged process of skillful labor at their works. The sense of the “real” that their paintings evoke is the result of thoughtful composition and meticulous depiction of details, which create an effect of vividness and veracity. One of the innovators of “real scene” painting was Suzhou painter and scholar Wen Zhengming (1470–1559), a key figure in the book. Wen valued the process of arrangement and ordering (

The approach my book develops deals with form in both abstract and concrete terms. The formal structures of paths and trees constitute pictorial spaces; arrangement and ordering of forms generate compositions. But these concrete pictorial forms also afford substantive hints as to how people organized real-life space, time, and community. I argue that artists’ emphasis on specific forms and details, their thoughtful compositions, and their extended painting process reflected their awareness of, and resistance to, the pace of daily life. I also argue that their paintings of familiar places were prompted by the impending transformation of their surroundings, as the Suzhou area was increasingly urbanized and becoming a commercial metropolis. The book looks at how the practice of painting defined place and self in a community within a changing social and physical environment.