Gruen is now well documented as a pioneer in the design of shopping malls, that achievement having constituted the center of interest of most publications on him until recently. During my residence at CASVA I chose instead to investigate Gruen’s architectural thought in relation to the evolution of the American city and to relate it to contemporary debates. The visiting fellowship constituted an essential step in my research, most importantly by providing the opportunity for me to consult the Victor Gruen papers in the Library of Congress.

Many times during his career Gruen exhorted planning authorities to “give the city back to the people.” In that interest he designed prototypes for the inhabitants of a better city to come. All of these projects questioned the radical changes experienced in the United States during the postwar period and attempted solutions at all architectural scales. New typologies and urban forms had to be invented to answer the new needs of a population using all the latest technologies, and the architect had a fundamental role: to reaffirm the mission of architecture, and of the architect, as opposed to the imperatives of omnipotent engineers. Consequently, what is often considered a paradox of Gruen’s career—that he worked simultaneously on the design of regional shopping centers and on revitalization projects for downtowns—was not paradoxical at all. As he explained in the mid-1950s, many American cities had already begun a process of transformation into “doughnuts”: depopulated cores ringed by suburbs. So the fight against chaotic suburban sprawl and the death of downtowns urgently called for comprehensive planning at the metropolitan scale as the only means of preventing simultaneous expansion of the “dough” and irremediable ruin of the “hole.”

Gruen, who was born in Vienna, never forgot his European background and always kept in mind an idealized image of the European city. Sharing neither Frank Lloyd Wright’s idea of Broadacre City, first proposed in the 1930s, nor the underlying concept of Jean Gottmann’s Megalopolis (1961), he had more in common with Jaqueline Tyrwhitt, José Luis Sert, and Ernesto Nathan Rogers presenting the findings of the Eighth International Congress for Modern Architecture (CIAM) in The Heart of the City: Towards the Humanization of Urban Life (1952), or with Jane Jacobs opposing Robert Moses and defending her ideas in The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961).

Gruen liked presenting himself as an architect working with hard reality, as opposed to the dreamers of idealized cities. An opponent of the segregation imposed by urban planners, he believed in an approach that mixed uses and functions, that is, three-dimensional planning. Gruen defended his ideas in numerous lectures, articles, and books that had a fundamental influence on contemporary debate well beyond the American coasts. During the 1960s and 1970s he found a favorable audience in most European countries, where his commissions included, besides projects for shopping centers, consulting for numerous master plans for new towns and for revitalization of old town centers. His papers at the Library of Congress testify to the important projects he undertook in Europe from the 1960s until his death. This European chapter of his career still has to be written, and I will dedicate a large part of my future research to it.

The last chapter of Gruen’s life is also the one in which, disenchanted, he realized that he had probably been a dreamer himself. During the 1970s, working on a new autobiographical work, he admitted: “What I feel I am today: A person, who—because he has learned the hard way what the realities are—is believing more than ever in the importance of ‘ideas,’ a person who hopes that, as a ‘dreaming realist’ or a ‘realistic dreamer,’ he can make a modest contribution to the progress of humanity, towards becoming more human.”

Members' Research Report Archive

Victor Gruen: A New Architecture for Our Urban Environment

Catherine Maumi, École nationale supérieure d’architecture de Grenoble

Paul Mellon Visiting Senior Fellow, June 15–August 15, 2012

In a lecture titled “Cityscape and Landscape,” given in Aspen, Colorado,

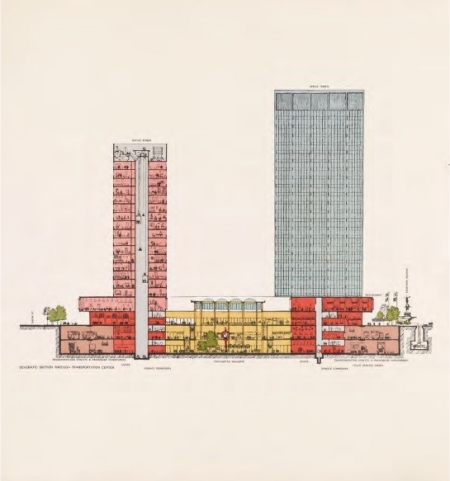

Schematic Section through Transportation Center, from “Revitalization Plan for the City Core of Cincinnati,” 1962, 17. Victor Gruen Papers, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division