Industrial Revolution

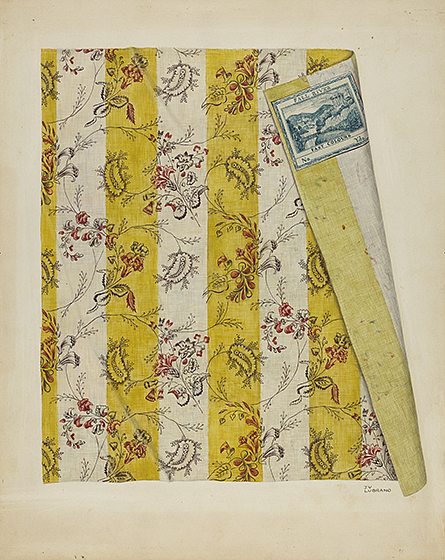

Cotton played a key role in the United States’ Industrial Revolution. By the mid-19th century, the United States supplied 61 percent of the world’s raw cotton, all of it grown in southern states. Textile mills in New England used raw cotton from the South to spin, dye, and eventually weave and print cotton fabric.

This textile sample—rendered in watercolor by an artist hired in the 1930s—was produced by the Robeson Company in Fall River, Massachusetts, between 1834 and 1848. The illustration is part of the Index of American Design, a collection of 18,257 watercolor renderings of American folk and decorative arts objects from the colonial period through 1900. Illustrators were hired by the federal government as part of a Depression-era work-relief program to document the “usable past” and preserve a national aesthetic.

What piece of design or material culture from today would you preserve for future generations?

Joseph Lubrano, Printed Textile, c. 1941, watercolor on paperboard, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Index of American Design, 1943.8.950

By the 1840s, when this portrait was made, textile mills had spread throughout New England. This merchant’s portrait is evidence of that growing industry. The sitter was affluent enough to commission his portrait and is shown in front of what made him wealthy. Rather than selling bulk textiles, however, this man probably supplied dry goods or manufactured dresses. Behind him are blue boxes that would have likely contained hats; bolts of calico, a printed cotton fabric, sit on shelves. Multiple groups benefited from calico printing at this time, including factory owners, textile merchants, and those who created goods using the fabric.

What markers of wealth and status do you see in your community today?

American 19th Century, Textile Merchant, c. 1840, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 1953.5.81

Crops of all kinds flourished in the Southern United States due to its warm climate, moderate rainfall, and rich soil. However, cotton was a commodity in high demand in the 19th century, and its growth and processing were made easier by the invention of the cotton gin in 1793 and the discovery of a new cotton species. These factors encouraged Southern planters to focus their growing efforts on the crop, and slaveholders increased their output by relying more heavily on enslaved human capital.

The House that Jeff Built is an abolitionist political cartoon made in 1863 during the Civil War. David Claypoole Johnston borrowed the structure of the British nursery rhyme “This Is the House That Jack Built” to illustrate how slavery and the cotton economy, led by Confederate President Jefferson Davis, were interdependent and dehumanizing.

According to this cartoon, what is the downfall of the Confederacy?

David Claypoole Johnston, The House that Jeff Built, 1863, etching in black on wove paper, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection, 2015.19.2810

The Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad, based in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, hired George Inness to depict and celebrate the railroad shortly after its 1851 incorporation. Inness’s painting features a train moving through a field of tree stumps, a sight increasingly common across the country as railroads were rapidly constructed in the second half of the 19th century. A roundhouse, depicted in the background, was not yet finished when Inness made the painting, but his patron requested it be included in the work.

Some scholars interpret this painting as an enthusiastic affirmation of industrial technology. Others understand it to be a lament for a rapidly vanishing wilderness. Given what you see in the painting, what do you think this artwork’s message is?

George Inness, The Lackawanna Valley, c. 1856, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mrs. Huttleston Rogers, 1945.4.1

In 1863 Thomas H. Johnson opened a photographic studio in Scranton, Pennsylvania, where he had easy access to clients in the coal and railroad industries. The Delaware and Hudson Canal Company (who later built the Delaware and Hudson Railway) hired Johnson to create a series of photographs depicting mining towns along railroad routes. Delaware and Hudson played a major role in developing and operating coal mines in northeast Pennsylvania. In this photograph, Johnson focused his camera on Waymart, a town that had sprung up along the railroad.

Compare this photograph to George Inness’s painting, The Lackawanna Valley. What similarities and differences do you see?

Thomas H. Johnson, Waymart, c. 1863–1865, albumen print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon, 2006.131.5

As part of a series documenting coal mines for the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company, Thomas H. Johnson set his camera upon this imposing structure set atop a mine opening in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Consider how Johnson shows the structure in comparison to the town and landscape. What do you think this photograph says about the coal industry?

There are more photographs of 19th-century railroads and industrial scenes than paintings. This is due in large part to the recent invention of photography in 1839. Photographers aligned themselves to modern industry and railroads preferred using the latest art form to promote their enterprise.

Thomas H. Johnson, Von Storch Shaft, Del. & Hudson Canal Co., c. 1863–1865, albumen print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund, 2016.152.1

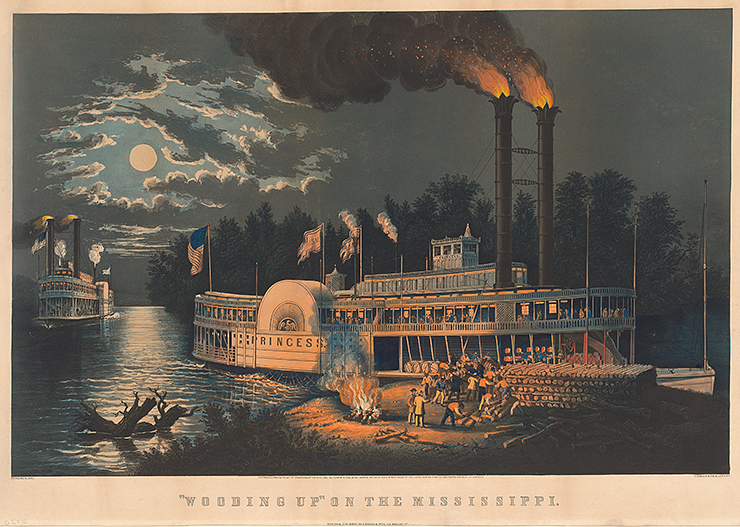

Steamboats dramatically altered transportation in the United States in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Powered by lumber or coal, steamboats replaced one-way flatboats, enabling faster two-way travel via canals and rivers. They also held greater capacity for carrying goods. Steamboats hastened the spread of settlers into what is now the middle of the United States, especially along the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers.

“Wooding Up” on the Mississippi from 1863 shows the showboat Princess stopping for fuel, perhaps in a race with Diana behind it. African Americans, likely enslaved, load lumber onto the boat, while white patrons, some of them slaveholders, populate the upper deck. In this work, Frances Flora Bond Palmer may have been hinting at the dangers of steamboat travel: moonlight shines on a snag (or tree) in the river, and the glowing fires would have reminded viewers of the all-too-common event of ship explosions. Palmer likely knew about the 1859 explosion of the showboat Princess in New Orleans, when dozens died because of faulty boilers.

Think about the details and themes presented in this work of art. If this image appeared in a newspaper, what do you think the adjacent headline might read?

Frances Flora Bond Palmer, “Wooding Up” on the Mississippi, 1863, color lithograph with hand-coloring on wove paper, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Donald and Nancy deLaski Fund, 2011.30.1

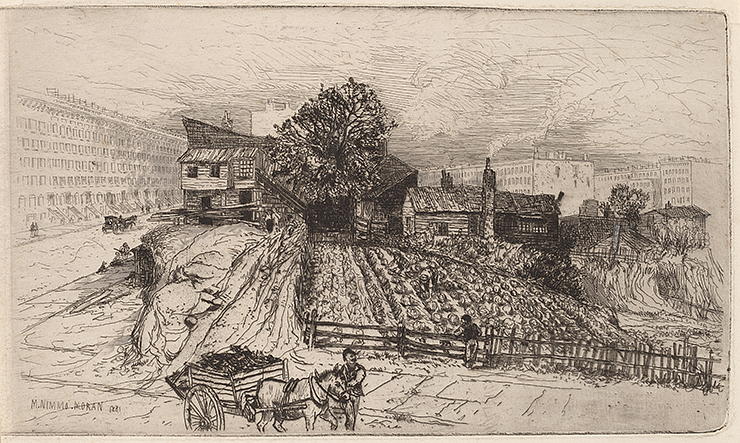

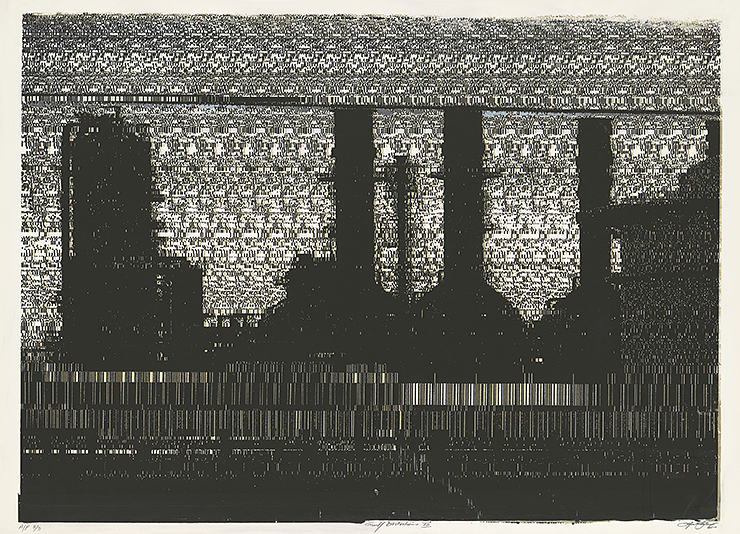

Mary Nimmo Moran was widely celebrated as an expert engraver in the 1880s and 1890s. Her depiction of industry surrounding a small vegetable farm bluntly illustrates the transition from agrarian to urban life that took place in the United States in the 19th century. In this etching, Nimmo Moran emphasized the farm’s stature by using heavier, darker lines in the printing process. She exposed that part of the copper plate to extra acid, which ate more deeply into the lines she had etched. As a result, these lines held more ink and appeared more saturated and bolder than the faint, soft outlines of the factories and high-rises.

Many US artists working at this time chose to flee from cities, especially New York, making intimate works depicting the landscape as a form of escape and relief from the stresses of modern life. These subjects appealed to many looking to purchase works of art.

Who do you imagine might have purchased a print like this? What kinds of contrasts do you see in the built environment where you live?

Mary Nimmo Moran, A City Farm—New York, 1881, etching in black, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.3579

Painter John George Brown kept a studio in New York a few blocks from the Hudson River. He often walked down to the docks, where he paid longshoremen more than their going rate to pose for sketches. The Longshoreman’s Noon illustrates a diversity of Irish and German workers, as well as a sole African American man, sitting on and in front of bales of cotton ready to ship.

Before the advent of the shipping container, longshoremen were essential to waterfront operations. They loaded and unloaded ships, moving hundreds of pounds of cargo that physically taxed their bodies. Work was often erratic, appearing and disappearing with the whims of shipping schedules, and steamships paid wages depending upon prevailing economic conditions. New York longshoremen went on strike multiple times in the late 1870s, while Brown worked on this painting. It is thought that the men at center are discussing news of their efforts published in the Sun newspaper.

Journalists criticized Brown for idealizing his subjects, including these longshoremen. He avoided showing the full realities and challenges of urban life, acknowledging that he made works of art for the public and collectors to enjoy. Knowing its background, what do you think about this painting?

John George Brown, The Longshoremen’s Noon, 1879, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, Gallery Fund), 2014.136.2

What do you picture when you think of cotton?

This photograph shows the interior of what was once the world’s largest cotton plantation. At left, African American men pack cotton into a large bale using a press; in the rear, cotton gins—machines that separate sticky seeds from plant fibers—are visible. Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin in 1793 accelerated cotton production in the United States, as well as the use of slave labor to harvest and process the crop. By 1899, when this photograph was made, slavery had been abolished for over 30 years, but cotton production was rebounding.

Dahomey Plantation was founded in 1833 by F. G. Ellis, who named the plantation after the Kingdom of Dahomey, the homeland of his enslaved workers in present-day Benin. Ellis was probably able to claim the land at this time because thousands of Native Americans had been forcibly removed under policies and orders enacted by President Andrew Jackson.

Imagine yourself in this scene: What do you think it would have felt like to work in this room? How does knowing the history of Dahomey Plantation and its land change your thinking about the photograph?

Detroit Photographic Company, Mississippi Cotton Gin at Dahomey, published 1899, photo-chromolithograph, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon and Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 2006.133.130

Addie Card was one of thousands of child workers whom Lewis Hine documented for the National Child Labor Committee from 1908 to 1924. The organization hired him to investigate and photograph child labor practices across the United States.

Child labor increased in the 19th century as factories and industries grew, and it was especially common in textile mills. Families relied on their children for income and employers took advantage of their small bodies and fingers to fix machines and fit into small spaces.

Lewis Hine’s photographs drew attention to unfair and unsafe child labor practices. But it was not until 1938 that the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed, regulating child labor—though agricultural labor was and still is excluded. Imagine yourself in Addie Card’s place. What do you think a typical day in her life would have been like?

Lewis Hine, Addie Card, 12 years old. Spinner in cotton mill, North Pownal, Vermont, 1910, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund, 2014.164.1

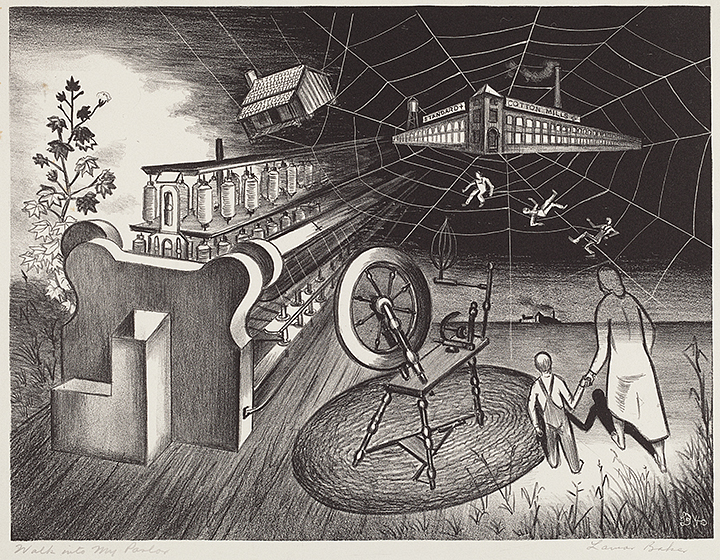

This print shows a montage of images related to the cotton industry in the South. In the foreground, a mother and child walk away from a spinning wheel toward a cotton mill, which has caught other workers in its web. A tall cotton plant on the left is juxtaposed with factory machinery.

By the 1930s, many southerners were trapped in the cotton industry’s cycle, growing the crop for cash and working the mills even as the market plummeted. The region’s longtime reliance on cotton and its lack of industry diversification and job opportunities led to widespread poverty.

Lamar Baker, an artist born and raised in Atlanta, said his objective was to make “social and moral comments by way of the lithographer’s art.” What social or moral commentary do you see in this work?

Lamar Baker, Walk Into My Parlor, 1940, lithograph, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.731

Hugo Gellert made Primary Accumulation 3 for an illustrated volume of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital. Das Kapital was written in the mid-19th century as the Industrial Revolution fundamentally altered work and life. Marx studied the English factory system and theorized that capitalism, with its incessant drive for profits and power, exploited workers and would eventually collapse.

Gellert selected what he called “essential parts” of Das Kapital and created corresponding prints. With this work, Gellert illustrated an aspect of primary (or primitive) accumulation, a concept which Marx described as a precapitalist phase wherein owners claim capital, often seizing it from others, in order to begin the capitalist cycle. Gellert shows the owners of production as more powerful and distinct from the working class. How does Gellert demonstrate the factory owner’s power?

Hugo Gellert, Primary Accumulation 3, 1933, lithograph, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.2026

Soledad Salamé traveled to Louisiana to document the aftereffects of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. The well, operated by BP, spilled 4.9 million barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico over the course of at least five months, making it the largest marine oil spill in history. This industrial disaster continues to negatively impact sea life and people living along the coast.

To create her Gulf Distortion series, Salamé faxed the photographs to herself, deliberately distorting the images. She printed them on plastic film using an ink that produces a shimmery appearance. Why do you think she may have distorted the original photographs in this way?

The Deepwater Horizon disaster raised questions about the petroleum industry, its environmental impacts, and how it is regulated. Compare this photograph to

Soledad Salamé, Gulf Distortion XII, 2011, color screenprint with interference pigments on plastic film, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Bob Stana and Tom Judy, 2016.148.46