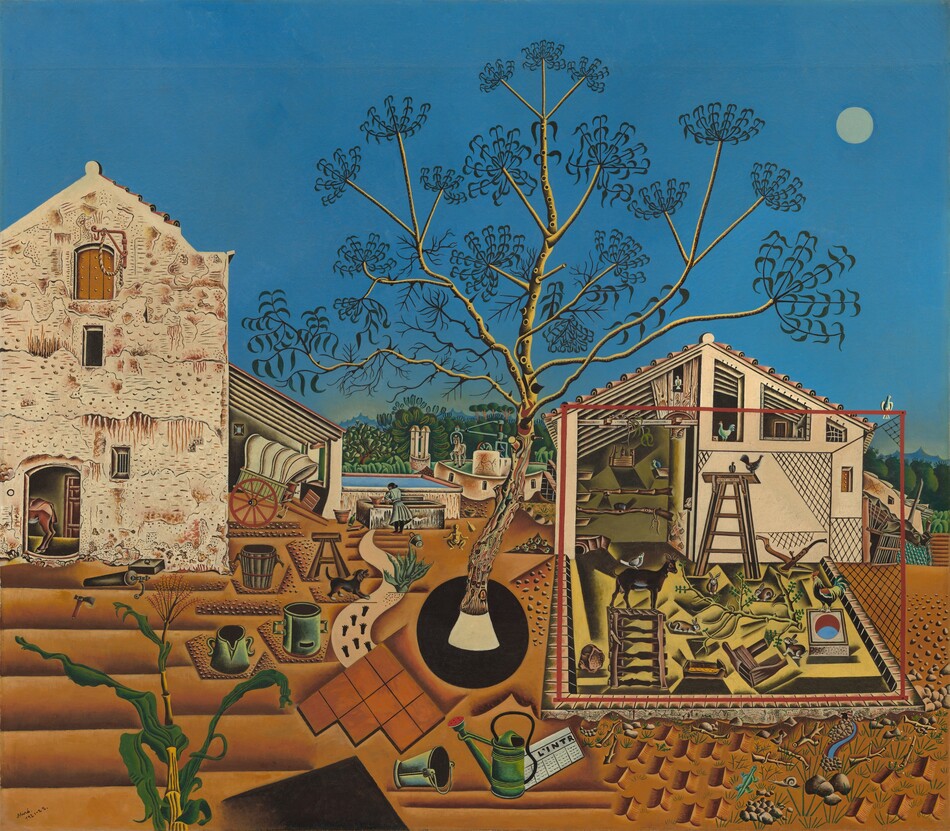

Art Comes to Life in Joan Miró’s "The Farm"

Joan Miró’s complex and captivating painting is full of life and mystery.

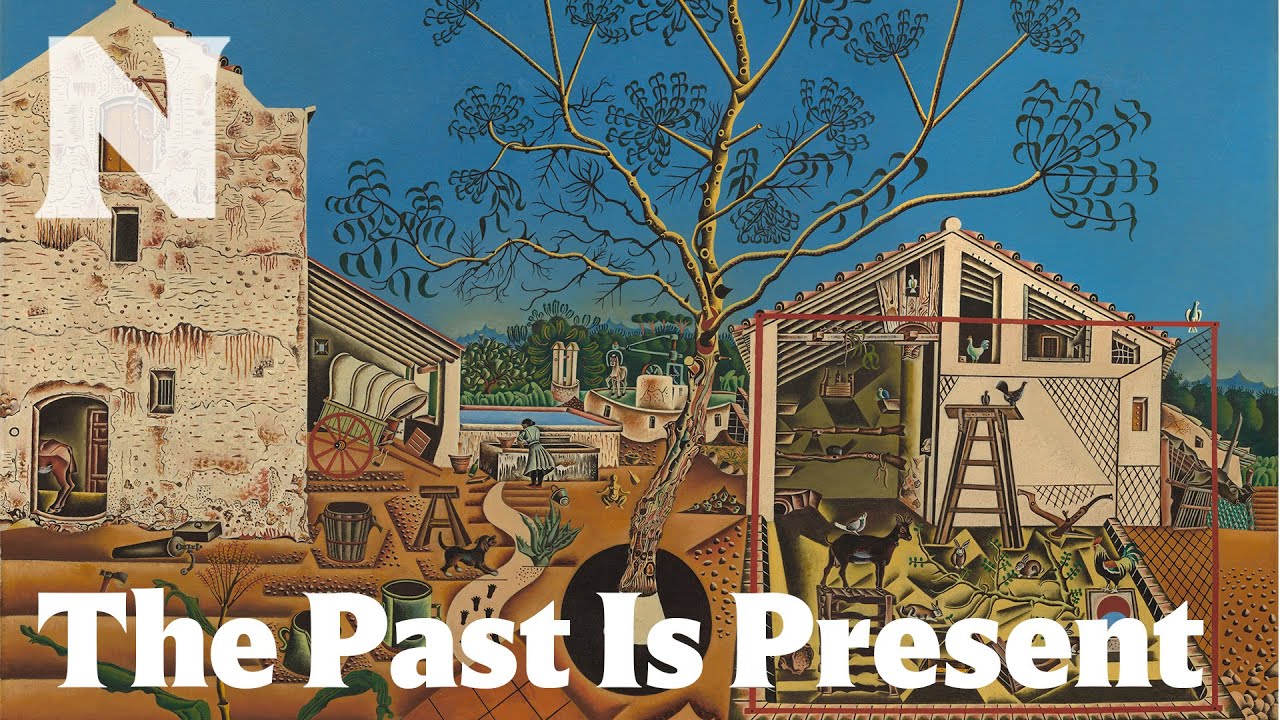

Catalan artist Joan Miró created The Farm over the course of nine months. The painting was so deeply personal to him that he compared this period to a pregnancy. And with its rich world of details and lack of clear meaning, the work does echo the complexity of a human life. It is a dreamlike vehicle for nostalgia and memory, at once universal and highly specific.

Learn more about The Farm, its mysterious details, and how it came into the hands of one of the greatest American writers of the 20th century.

A Fantastical Painting of Mont-roig

In 1920, Miró left his hometown of Barcelona for Paris, where he hoped to advance his career as an artist. Though he spent much of his time in the French capital, Miró returned to Spain each summer to stay at his family’s farm in the small town of Mont-roig del Camp.

Drawing inspiration from the striking Catalan countryside, Miró created this sprawling depiction of the farm between summer 1921 and winter 1922.

One of the most intriguing mysteries behind this work is its arresting visual style. Like Miró himself, the painting resists categorization.

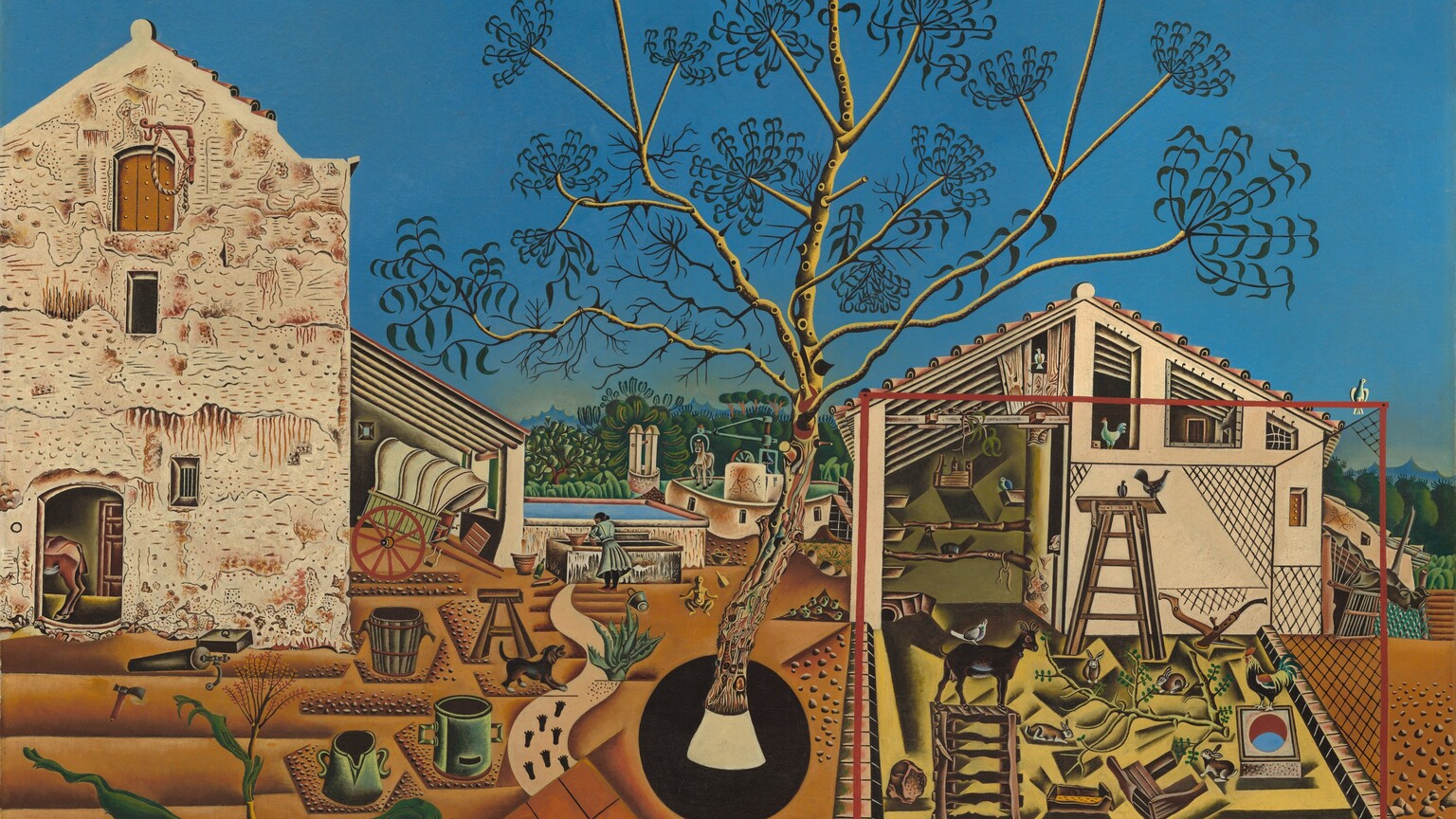

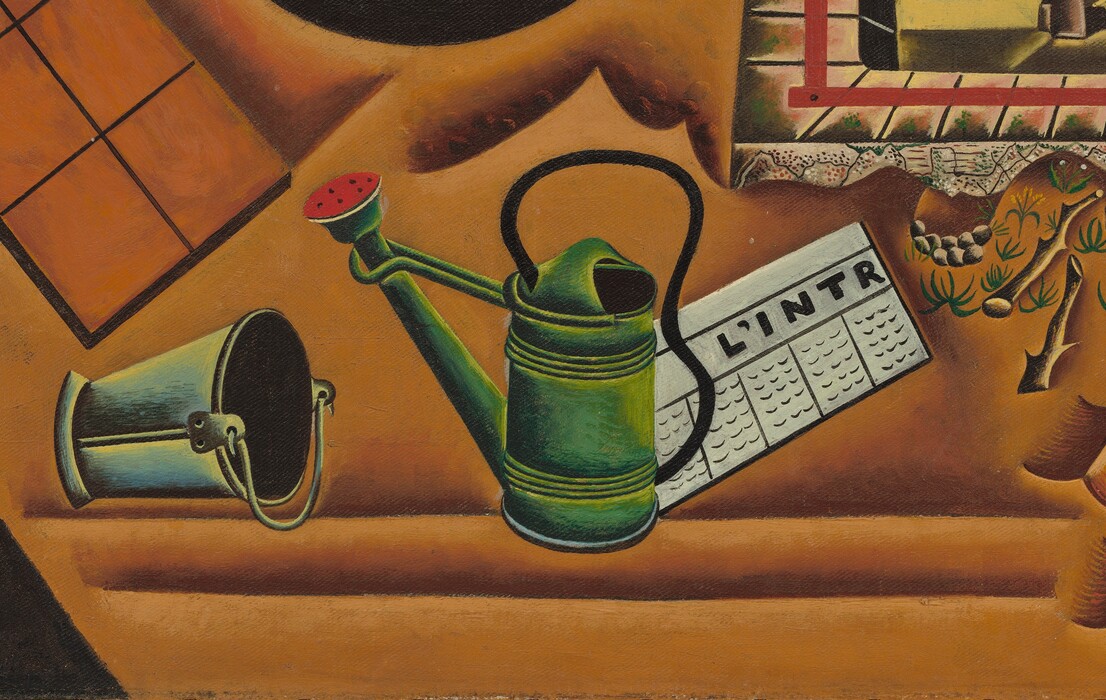

The Farm combines elements of cubism and realism. Objects appear from varying points of view, a technique common in cubism. But they are rendered with great detail, which is characteristic of realism.

The result is a highly detailed work full of precisely painted items that also feels like something out of a fantasy. Miró created a bustling scene of daily life in Mont-roig, but threw in quite a few mysterious elements.

Look Closely, Search for Meaning

What’s happening in this work?

But some elements of The Farm have clear—or at least clearer—meanings.

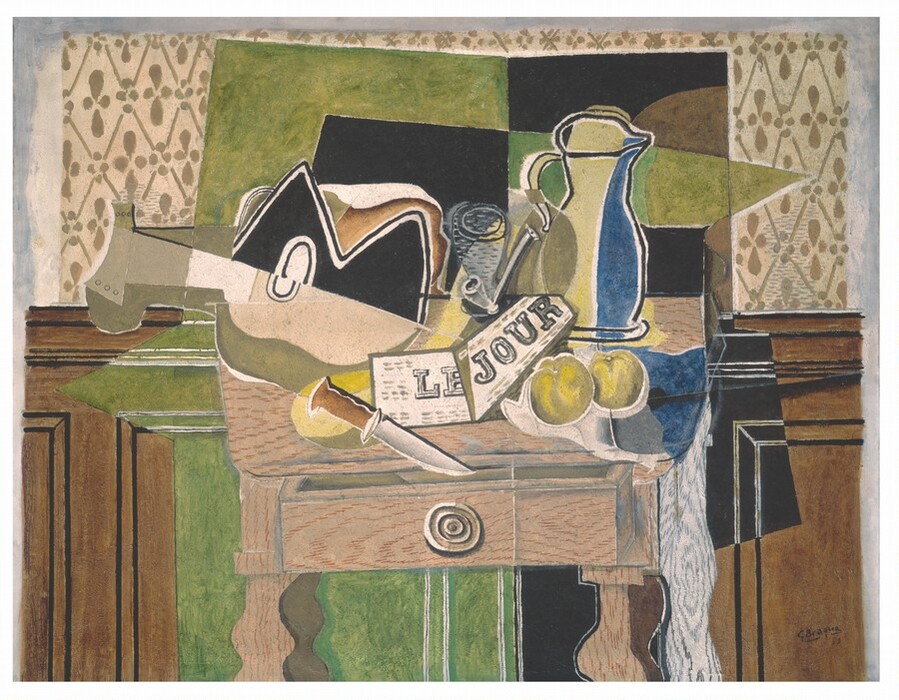

Note the newspaper near the bottom of the painting, sitting in a dusty field. While this might be a strange spot to leave a paper, its presence may reference Miró’s connections to the cubist movement. Artists like Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Juan Gris often painted or collaged newspapers into their cubist works.

Miró also used this painting to communicate a vision of humble rural life—even if it didn’t quite match reality. The painter chose not to include his family’s grand country house in the scene.

And notice the cracked, crumbling wall of the barn. Miró probably took artistic liberties here—the structure was likely not in such a dilapidated state.

Compare the painting with this photograph of the home, now the Fundación Mas Miro.

Ernest Hemingway and The Farm

At first, Miró struggled to sell the painting. He later said that no art dealer in Paris “even wanted to look at it.” Eventually, Paul Rosenberg—a gallerist who represented Miró’s friend Pablo Picasso—agreed to display The Farm on consignment. When it failed to sell, Rosenberg suggested cutting the painting into eight pieces and selling them individually to better fit in small Parisian apartments.

Miró was distraught. He considered this one of his greatest works, writing that it “was the summary of [his] whole life (spiritual and poetic) in the countryside.”

Luckily, this masterpiece would soon become the singular obsession of another notable Paris resident.

During his time in Paris, Miró befriended American writer Ernest Hemingway. By 1925, Hemingway had become enthralled with The Farm and planned to buy it. His friend poet Evan Shipman also wanted the painting. According to Hemingway, the two writers shot dice for it, and he won. To pay for it, Hemingway collected money from patrons in restaurants and cafés throughout Paris.

The painting became one of Hemingway’s prized possessions. He wrote that it “has in it all that you feel about Spain when you are there and all that you feel when you are away and cannot go there.”

But he may have said it best in an article for the French literary and artistic journal Cahiers d’Art in 1937. After explaining the story behind buying the painting and extolling its virtues, he concluded, “This is too long now and the thing to do is look at the picture: not write about it.” The fascinating work that captured this great writer’s imagination still resonates today.

You may also like

Interactive Article: Layers of Power in "The Feast of the Gods"

At first glance, this painting looks like a great party. But it’s more complicated than that.

Interactive Article: Art up Close: Judith Leyster, the Leading Star of Her Time

Her paintings were passed off as the works of her male contemporaries. Get to know 17th century painter Judith Leyster through the hidden details of her lively self-portrait.