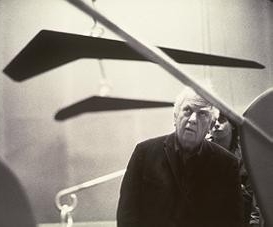

With scrap metal scarce in the midst of World War II, Alexander Calder turned to hand carving small pieces of wood into mostly abstract shapes and attaching these—some painted, some unpainted—to a network of rigid wires. After consulting his friends Marcel Duchamp and curator James Johnson Sweeney, Calder decided to call the roughly 29 stationary works “Constellations.” These delicate tabletop constructions—Vertical Constellation with Bomb among the most complex—constituted what Calder called “a new form of art.” The Constellations afforded the artist another sculptural means, beyond his well-known mobiles, to investigate the organization of forms into open, abstract compositions.

Vertical Constellation with Bomb includes 10 wooden pieces, mostly geometric or biomorphic, connected by thin steel wires painted red. Five of the shapes are unpainted, and four are painted a deep blue. The falling “bomb” is a combination: the nose is unpainted, the body is blue and white, and the attention-grabbing fins are decorated with a pattern of brightly colored triangles—red, orange, blue, black, white, and yellow.

Astronomy interested Calder from an early age, and often he related his work to cosmic space. The Constellations derived from the artist’s early 1930s series of standing sculptures, “Universes,” that resembled orreries (astronomical devices that demonstrate the orbit of planets in the solar system); in relation to the Universes series, Calder described the universe itself, with its “detached bodies floating in space,” as “an ideal source of form.” Vertical Constellation evokes this idea of the cosmos through its broad disposition of variably sized wooden pieces, which define an expansive three-dimensional space. Likewise, the repetition of shapes—such as the two pieces projecting from the top of the sculpture, echoing larger versions below—suggests movement into distant horizons.

Calder’s Constellations share affinities with surrealist works by Jean Arp, Joan Miró, and Yves Tanguy, all of whom explored situating points or forms in loose configurations through space or across a painted field. Arp and Miró even called some of their works Constellations, highlighting the privileged place that cosmological metaphors held in the development of abstraction in the 1930s and 1940s.

Vertical Constellation’s direct treatment of a contemporary war subject is an anomaly in Calder’s work. The falling bomb doubtless appealed to him formally, but it is also conceivable that the artist sought to comment ironically on the violence at hand by transforming a deadly weapon into a colorful, toylike object.