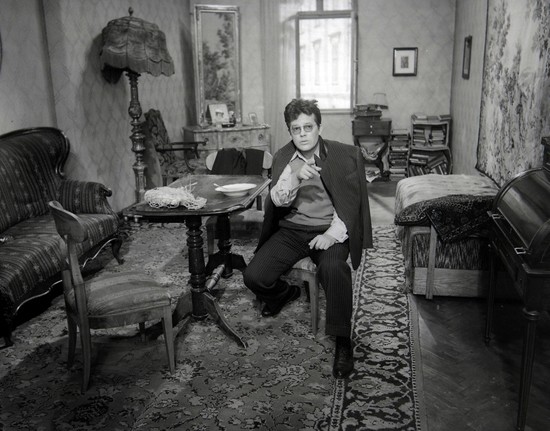

still from How to Be Loved, courtesy Filmoteka Narodowa, Warsaw

Monolithic Diversity: Films by Wojciech Jerzy Has

Three films by the late Polish director Wojciech Jerzy Has (1925-2000)—How to Be Loved, The Saragossa Manuscript, and The Hourglass Sanatorium—appear unrelated in terms of their genre, setting, and character. Yet, the cinematic realities created in those films reveal broad underpinning qualities common to the three works.

Has’s path to feature filmmaking was long and complex. The future director of The Saragossa Manuscript was born in 1925 in Kraków. His youth was marked both by the hardship of World War II and a keen interest in painting. Has attended an underground art course during the German occupation and studied at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts after the end of the war. The same period saw the beginning of his cinematic career, with participation in a film course that functioned as a quasi-film school given the absence of such institutions in the country (the film school in Łódź was not established until 1948) and employment at the Warsaw Documentary Film Studio (WFD). Despite very promising career prospects as a painter, Has chose to devote himself to filmmaking. Nearly a decade passed, however, before his feature debut was released in 1957.

It should be noted that Has’s early days in the film industry coincided with the implementation of Stalinist policies in Poland, a quasi-independent country left in the sphere of Soviet political influence following World War II. Like all other areas of economic, cultural, and social life, cinematography remained under the state’s strict control and supervision. Censorship was rife and the making and release of films that did not follow official propaganda could be thwarted or indefinitely postponed. The film industry was entirely state-owned, creating a highly institutionalized landscape in which the authorities had broad powers to determine the career paths of individual filmmakers, allowing or denying directors the right to choose their own projects.

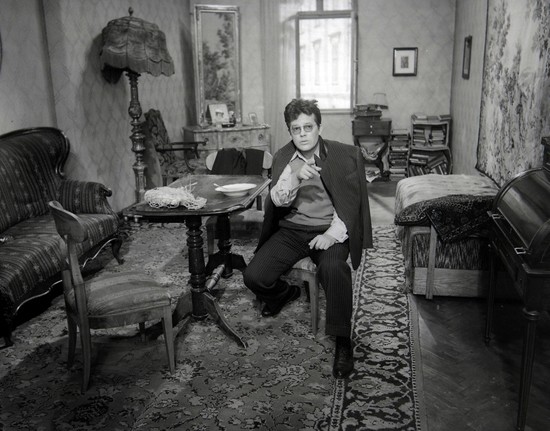

still from How to Be Loved, courtesy Filmoteka Narodowa, Warsaw

Has distanced himself from politics. His work did not stand in opposition to the dominant political regime, but he never made any aesthetic or political concessions either. As a director, he faced politically motivated constraints imposed by the authorities throughout his career under the communist regime. Still, Has refused to assume the role of politically repressed victim and pursued his cinematographic visions against all obstacles. His first film, Harmony (Harmonia), a midlength film from 1948, and his documentary Brzozowa Street (Ulica Brzozowa) from 1949 were banned from distribution. Has was transferred from his position at the WFD to the Educational Film Studio (WFO) in Łódź in reaction to his film My City (Moje miasto) from 1950.[1] Heavily immersed in politics, the institutional framework of filmmaking prevented him from debuting as a feature filmmaker before the political thaw that followed the death of Joseph Stalin, when the communist regime was relaxed in Poland. That long wait may have been one of the reasons why Loop (Pętla) from 1957 was universally recognized as a mature film debut, even though it received mixed critical reviews.

Despite the fact that Loop is relatively distinct in time and style from Has’s most renowned works from the following decades, it emanates a certain quality that seems common to perhaps all of his films. The film tells the story of a day in the life of Kuba, an alcoholic who seems determined to kick the habit. Unable to deal with the pressure, he kills himself the following morning. The film’s scenery does not function merely as a background, an artificial environment that seeks to appear natural through the camera lens. One of the most prominent biographers and critics of Has, Konrad Eberhardt, highlights the director's pursuit to connect the setting with the experiences and mental states of the characters, and thus link it to the human psyche. The critic describes the scenery of Loop as a nightmarish environment that corresponds to the nightmarish experience of the protagonist. The cluttered space of Kuba’s apartment, the grim city that he roams, the bar where he drinks—everything appears to be in a state of osmosis with the main character's mental sphere.[2] The interiors portrayed in Loop are characterized by a wealth of objects and decorations, radiating perverse art deco lushness. Similar scenery will surround the protagonists of Has’s future films as the director develops his rich film setting style.

still from How to Be Loved, courtesy Filmoteka Narodowa, Warsaw

The scholar Marcin Maron is right to remark that such spaces, cluttered with objects from the past, convey a hidden presence of memory, thus establishing time as a significant factor that regulates the spatial dimension of Loop’s reality.[3] This can also be observed in How to Be Loved (Jak być kochaną) from 1962, where the effects of time on the setting manifests itself not only through the persistence of memory in spaces immersed in bygone days. This film builds an even stronger link between the temporal and spatial dimensions. The setting plays an important role in differentiating between the present and the past, as the plot of the film relies heavily on retrospection, specifically the memories of Felicja, an actress aboard a plane to Paris who reminisces about events that took place during World War II. It is in hindsight that the entire story of her dramatic love unfolds. Eberhardt contrasts Has’s signature cluttered spaces that provide the setting of scenes from the past with the sterile environment of the aircraft in the scenes from the present.[4]

Once again, the setting becomes subordinated to time, the fundamental force and theme of Has’s films, as many commentators of his works agree. In terms of the temporal order of the filmic reality, Maron points out that whereas the previous films focussed on an individual and subjective perception of time, How to Be Loved introduces a new level related to the historical period of the war and occupation, which determines the fate of the protagonists.[5] The film was Has’s first work to receive unanimous critical acclaim, and it consolidated his position as a filmmaker. Even so, his most renowned and ambitious cinematographic projects were still to come.

Next: A Film Found in Saragossa

[1] Anne Guérin-Castell, “Wojciech Has. Une vie pour le cinéma,” last modified August 30, 2005. (back to top)

[2] Konrad Eberhardt, Wojciech Has (Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe, 1967), 19. Eberhardt links this quality of the setting in Has’s films to expressionism in cinema, especially in Germany in the 1920s. (back to top)

[3] Marcin Maron, Dramat czasu i wyobraźni: filmy Wojciecha J. Hasa (Kraków: Universitas, 2010), 75. (back to top)

[4] Eberhardt, Wojciech Has, 53. (back to top)

[5] Maron, Dramat czasu I wyobraźni, 79. (back to top)