Traces of History

Chuck Close, American, born 1940, Kara, 2007, daguerreotype, 21.59 × 16.51 cm (8 ½ × 6 ½ in.), © Chuck Close, courtesy Pace Gallery, 2011.110.1

Introduced in 1839, daguerreotypes are one of the earliest photographic processes. Sometimes referred to as a “mirror with a memory,” they are made on highly polished, silver-coated copper plates. Intrigued by their clarity, detail, and luminosity, Close began making daguerreotypes in 1997. Rather than merely reviving an outmoded process, Close strove “to banish the nostalgia from something old to make it about our time.’’ In Kara he merges this 19th-century technique with contemporary questions of race and identity by using strong backlighting to evoke artist Kara Walker’s own distinctive, cut-paper silhouettes. For Walker, the simplicity of silhouettes often reduces humans to caricatures, mirroring the way racial stereotypes operate: “The silhouette says a lot with very little information, but that’s also what the stereotype does.”

Carrie Mae Weems, American, born 1953, After Manet, 2002, chromogenic print, 2015, 78.74 × 78.74 cm (31 × 31 in.), © Carrie Mae Weems, courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

This photograph and the one in the following slide, part of a larger project titled May Days Long Forgotten, weave together diverse May Day associations, including the revolutionary zeal of International Workers Day and the promise of spring’s renewal. Weems also pays homage to the traditions of art history: the round format suggests circular tondi popular in the Renaissance, the convex glazing mimics antique mirrors, and the sepia tone evokes 19th-century photographs. The pastoral setting echoes one of Édouard Manet’s most radical paintings, Le déjeuner sur l’herbe. Like the woman in the foreground of Manet’s masterpiece, some of the girls in Weems’ photographs directly engage the viewer. But Weems’ African American girls introduce a subject seldom seen in the history of art. “I’m very aware,” the artist has noted, “of linking my figures to a historical narrative or tradition and reexamining that tradition by putting in someone who was never there.”

Carrie Mae Weems, American, born 1953, May Flowers, 2002, chromogenic print, 2013, 78.74 × 78.74 cm (31 × 31 in.), © Carrie Mae Weems, courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, 2014.3.1

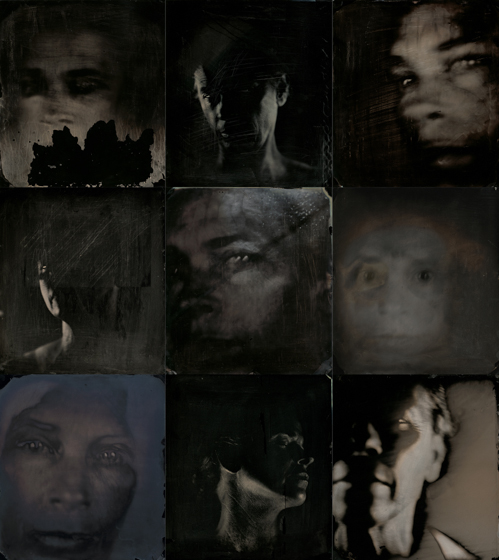

Sally Mann, American, born 1951, Untitled (Self-Portraits), 2006–2012, nine ambrotypes, each: 38.1 × 34.29 cm (15 × 13 ½ in.), © Sally Mann, courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery, 2013.83.1.1-9

Best known for photographs of her family, Mann began to make self-portraits after a severe horseback-riding accident in 2006. Determined to work but unable to lift her heavy camera, she set it up in one position and photographed herself repeatedly using the 19th-century ambrotype process. Ambrotypes are collodion negatives that are made either on clear glass placed against a dark background to make the image appear positive, or, as Mann has done, on black glass. While earlier photographers prized the fine detail of collodion negatives and worked diligently to pour the sticky substance on the glass smoothly without bubbles, streaks, or drips, Mann exploits these blemishes. Allowing the physical surface of the glass plates to convey a sense of disintegration and loss, Mann seems to confront her own physical dissolution in this work.

Sally Mann, American, born 1951, Untitled (Self-Portraits), 2006–2012, nine ambrotypes, each: 38.1 × 34.29 cm (15 × 13 ½ in.), © Sally Mann, courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery, 2013.83.1.1-9

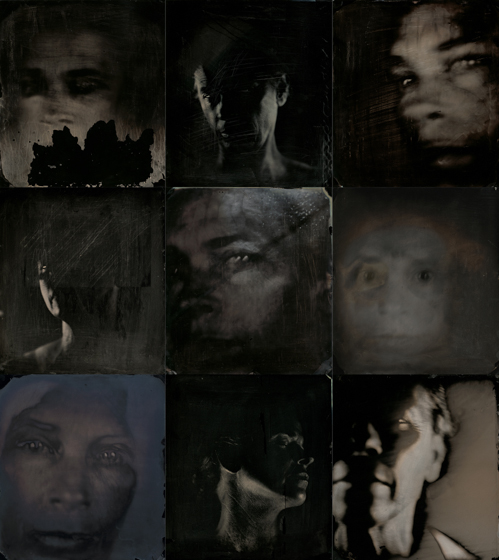

Myra Greene, American, born 1975, Untitled [Ref. #77] from Character Recognition, 2007, ambrotype, 9.9 × 7.5 cm (3 7/8 × 2 15/16 in.), © Myra Greene, 2012.23.7

From its inception, photography has been used as a tool for ethnography, often in support of pseudoscientific theories of racial classification. Greene, using the 19th-century ambrotype process, alludes to photography's historical role in teaching people to see African Americans not as individuals but as racial types. "Do we recognize character just by looking at the shape of a nose or the color of skin?" she asks. In each of these works, Greene presents a fragment of her own face and manipulates the tone of the photographs to explore the metaphorical significance of blackness. While some of the images are reminiscent of conventional ethnographic documentation, others present such extreme close-ups that they render the subject nearly abstract; still more capture expressive, individualistic gestures that defy generalization.

Myra Greene, American, born 1975, Untitled [Ref. #60] from Character Recognition, 2006, ambrotype, 9.9 × 7.5 cm (3 7/8 × 2 15/16 in.), © Myra Greene, 2012.23.3

Myra Greene, American, born 1975, Untitled [Ref. #56] from Character Recognition, 2006, ambrotype, 10.2 × 7.7 cm (4 × 3 1/16 in.), © Myra Greene, 2012.23.2

Myra Greene, American, born 1975, Untitled [Ref. #72] from Character Recognition, 2007, ambrotype, 10 × 7.5 cm (3 15/16 × 2 15/16 in.), © Myra Greene, 2012.23.5

Myra Greene, American, born 1975, Untitled [Ref. #63] from Character Recognition, 2006, ambrotype, 10.1 × 7.4 cm (4 × 2 15/16 in.), © Myra Greene, 2012.23.4

Myra Greene, American, born 1975, Untitled [Ref. #20] from Character Recognition, 2006, ambrotype, 7.4 × 10.1 cm (2 15/16 × 4 in.), © Myra Greene, 2012.23.1

Myra Greene, American, born 1975, Untitled [Ref. #75] from Character Recognition, 2007, ambrotype, 10.5 × 7.5 cm (4 1/8 × 2 15/16 in.), © Myra Greene, 2012.23.6

David Maisel, American, born 1961, History’s Shadow GM12, 2010, inkjet print, 100.33 × 75.57 cm (39 ½ × 29 ¾ in.), 2012.43.2

In the haunting series History’s Shadow, Maisel photographed x-rays of sculptures in the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. He placed each x-ray on a light box and photographed it using a long exposure. He then scanned the new negative to make a digital file, which he further manipulated to create pictures that appear at turns both ghostly and alive. Revealing “the shape-shifting nature of time itself,” as Maisel says, his photographs capture both the internal structure and the external details of the original sculptures, showing their past history and present state.

David Maisel, American, born 1961, History’s Shadow GM16, 2010, inkjet print, 74.93 × 100.97 cm (29 ½ × 39 ¾ in.), 2012.43.3

Adam Fuss, British, born 1961, For Allegra, from the series "My Ghost," 2012, daguerreotype, 59.69 × 96.52 cm (23 ½ × 38 in.), 2013.112.1

Fuss' daguerreotypes, some of the largest ever made, underscore how objects evoke memories and signal the passage of time. He created For Allegra by scanning and then digitally manipulating three 1864 negatives by John Murray of the Taj Mahal, the 17th-century memorial in Agra, India, built by Mughal emperor Shah Jahan in honor of his wife. In the 19th century, a daguerreotypist would have considered the work's blue color—the result of overexposure—a defect; Fuss sees it as emblematic of sadness and a sense of loss.

Binh Danh, American, born Vietnam, 1977, Sugar Pine Tree, Yosemite, CA, April 2, 2012, 2012, daguerreotype, 21.59 × 16.51 cm (8 ½ × 6 ½ in.), 2013.54.1

After fleeing Vietnam with his family at age two, Danh settled in California, but never visited Yosemite National Park as a child. His family’s escape through Southeast Asian jungles and experiences in refugee camps ruled out vacations to the wilderness. As a result, Danh’s initial connection to Yosemite was through the celebrated photographs of Ansel Adams (1902–1984) and Carleton Watkins (1829–1916). In 2011, Danh visited the park and made a series of daguerreotypes that brings a reflectivity to the scene, both literally and metaphorically. Stepping before the mirrorlike photographs, viewers may glimpse their own image in the midst of one of America’s national treasures, allowing anyone to see him- or herself within this iconic landscape.

Binh Danh, American, born Vietnam, 1977, Lower Yosemite Falls, Yosemite, CA, October 13, 2011, 2011, daguerreotype, 21.59 × 16.51 cm (8 ½ × 6 ½ in.), 2013.69.1

Matthew Brandt, American, born 1982, Salton Sea C1, 2007, salted paper print, 75.57 × 96.52 cm (29 ¾ × 38 in.), 2014.31.1

Brandt explores the early history of photography by making salted paper prints, a process popular in the 1840s and 1850s that produces photographs with a matte surface and diffuse details. To create this print, he soaked drawing paper in water collected from California’s Salton Sea, allowing the impurities in the water to affect the tonality and texture of the piece. Incorporating physical elements of what he photographs directly into his prints, Brandt remarked that “it was a way to literally . . . use the thing to represent the thing,” blurring the line between the photograph and its subject.