Picasso: The Early Years, 1892-1906

Early Youth

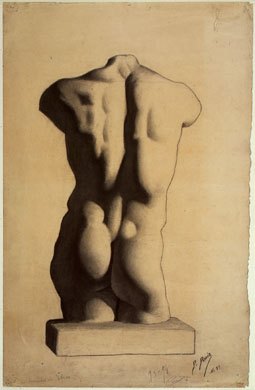

Pablo Ruiz Picasso was born on October 25, 1881, in the Spanish coastal town of Málaga, where his father, José Ruiz Blasco, was an art instructor at a provincial school. Picasso began to draw under his father's tutelage and studied in various art schools between 1892 and 1897, including academies in Barcelona and Madrid. Working from live models as well as plaster casts of Greek and Roman sculpture, the young artist displayed a precocious command of academic draftsmanship (Study of a Torso) that would be evident throughout his career, later serving as the vehicle for some of his most original work.

This drawing by Picasso was in fact based upon a drawing of a plaster cast by Charles Bargue (c. 1826–April 6, 1883). Bargue was a French artist, lithographer, and painter, and most widely remembered for his Cours de dessin, conceived in collaboration with Jean-Léon Gérôme.

Gerald M. Ackerman, Charles Bargue | Drawing Course with the collaboration of Jean-Léon Gérôme (Paris: ACR Edition Internationale, 2003), 83.

Study of a Torso, After a Plaster Cast, 1893/1894, Musée Picasso, Paris © 1997 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In addition to academic classicism, Picasso's student work manifested a less idealized manner of representation in genre subjects and portraiture. The artist executed many family portraits at this time and depictions of local figures such as an old sailor named Salmerón (The Old Fisherman), who was hired as a model by Picasso's wealthy uncle in Málaga. In Madrid Picasso's art was also shaped by visits to the Prado, where he studied works by Spanish old masters Velázquez and Ribera, as well as by El Greco (the latter's stylized mannerisms would soon play an important role in Picasso's work). During this period Picasso produced several large-scale pictures on religious and allegorical themes, which appeared in official exhibitions. At the same time, he displayed an irreverent playfulness in works such as the Self-Portrait in a Wig, in which the artist masquerades as an eighteenth-century Spanish noble.

The Old Fisherman (Salmerón), 1895, Museu de Montserrat, Barcelona © 1997 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Modernism in Barcelona and Paris

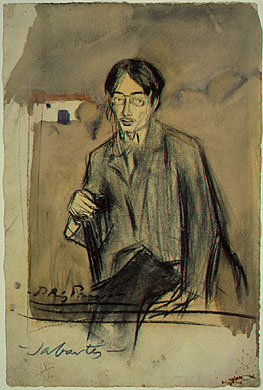

In Barcelona in 1899 Picasso rejected academic study and changed artistic direction by joining the circle of young avant-garde artists and writers who gathered at a local tavern, Els Quatre Gats. Known as modernistes or decadentes, this community assimilated contemporary international trends such as symbolism, which emphasized the evocation of atmosphere and mood over literal description. In illustration, poster design, and other graphic arts, they turned to French art nouveau, which was distinguished by sinuous contour lines, simplified shapes, and artificial colors. Influences included Théophile Steinlen and Toulouse-Lautrec, whose impact can be seen in Picasso's work. Adapting this style, the artist produced numerous portraits of friends and acquaintances from Els Quatre Gats, among them Carles Casagemas and Jaime Sabartès (Sabartès Seated). Picasso included many of these in his first solo exhibition, which opened at the tavern in February 1900. In their art and writing young modernistes also devoted themselves to political anarchy and related social causes, including sympathy for the plight of the urban poor. Indeed, subjects from the streets of both Barcelona and Paris would soon occupy Picasso's work.

Sabartès Seated, 1900, Museu Picasso, Barcelona © 1997 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Picasso traveled to Paris several times beginning in 1900 before settling there permanently in 1904. Many aspiring avant-garde artists at the turn of the century moved to the French capital, where the work of post-impressionist painters Van Gogh, Cézanne, Seurat, Gauguin, and their disciples could be seen at the galleries and Salons. With vigorous comprehension, Picasso rapidly assimilated many of these influences. Between 1900 and 1901 his work reflects a variety of new styles and techniques, such as the introduction of bright, unmixed colors. Subjects included typical scenes of Parisian nightlife, such as his depiction of the dance hall Le Moulin de la Galette, as well as portraits, such as the bold, posterlike image of Pere Mañach, an art dealer who promoted Picasso's work at the time.

Picasso's most important early exhibition took place in 1901 at the gallery of Ambroise Vollard (who represented the post-impressionists and younger members of the French avant-garde). Consisting largely of paintings and drawings in a variety of styles created during a brief period of intense activity, the exhibition was a financial success for Picasso and brought him commissions for posters and magazine illustrations. It was reviewed by one critic, Félicien Fagus, as the debut of a "brilliant newcomer." Fagus also wrote that "Picasso's passionate surge forwards has not yet left him the leisure to forge a personal style."

Le Moulin de la Galette, 1900, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection, Gift Justin K. Thannhauser, 1978 © 1997 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Blue Period

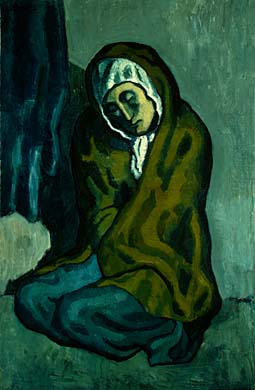

In late 1901 Picasso's work took a dramatic turn. Beginning with several paintings that commemorated the recent suicide of his friend Casagemas, the artist's themes grew solemn and dark, and he adopted a palette devoted almost exclusively to shades of blue. The monochromatic use of blue was not uncommon in symbolist painting in Spain or France, where it was associated with representations of melancholy or despair. Such associations were well suited to Picasso's subject matter, which focused on denizens of the underclass. Along with the many indigents and misérables he portrayed in dark corners of unnamed streets and cafés (Crouching Woman), Picasso depicted prostitutes and their children at the women's prison of Saint-Lazare in Paris. Rather than show the specific circumstances of their misfortune, however, he idealized his figures. Using elongated proportions derived from El Greco, Picasso metaphorically allows his subjects to escape their worldly fate and occupy a utopian state of grace. Some are afflicted with blindness, a physical condition that symbolically suggests the presence of spiritual inner vision.

Crouching Woman, 1902, Collection Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Anonymous Gift, 1963 © 1997 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

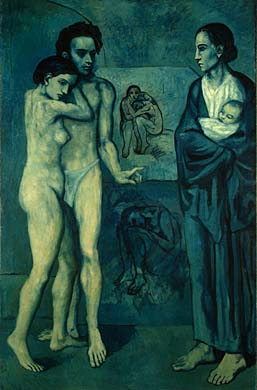

Throughout the Blue period Picasso also created intimate portraits of his bohemian comrades and acquaintances in Paris and Barcelona, who sought to identify themselves with society's dispossessed. Their relative poverty lends Blue period subjects a certain self-pitying air. Indeed, in his masterpiece La Vie Picasso originally planned to depict himself as the protagonist, although he ultimately substituted a portrait of Casagemas. Historians interpret this somewhat mysterious work as an allegory of birth, death, and redemption. Picasso's biographer John Richardson has further observed the appearance of gestures borrowed from Tarot cards and other arcane elements of mysticism. In this context the figures may refer to the theme of sacred and profane love, although precise meanings remain unclear.

La Vie, 1903, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of the Hanna Fund © 2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In the spring of 1904 Picasso finally settled in Paris, moving into a tumbledown residence in Montmartre known as the Bateau Lavoir, named for its resemblance to a laundry barge. The Parisian cabaret Le Lapin Agile replaced Els Quatre Gats as a gathering place for his circle of friends, sometimes known as la bande à Picasso ("the Picasso gang"). Refining the exaggerated, now almost skeletal proportions of his figures, Picasso produced his most important early print, The Frugal Repast, which depicts a destitute couple sharing a paltry meal of bread and wine. In addition to poverty and dolor, Picasso's late Blue period work expresses a wider range of emotion. Intimacy, affection, and tender eroticism are seen in portraits of two mistresses, Fernande Olivier and a model now known only as Madeleine, the subject of Woman in a Chemise, one of the artist's most delicate and sympathetic images. Perhaps unexpectedly, Picasso produced scurrilous caricatures and other satiric images at this time, indulging what became a lifelong taste for parody.

Woman in a Chemise, 1904, Tate Gallery, London, Bequeathed by C. Frank Stoop, 1933 © 1997 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Saltimbanque

In 1905 Picasso abandoned the palette and subject matter of the Blue period, turning to images of fairground and circus performers, whom he depicted in a range of chalky red hues. Accordingly, this phase of his work has come to be known as the Rose period. Picasso observed these figures firsthand at the Cirque Medrano, as well as in the streets and outskirts of the city, where a migrant community of acrobats, musicians, and clowns-- saltimbanques--entertained passing spectators. Such figures commonly occur in romantic and symbolist art and verse (from Daumier and Seurat to Baudelaire and Rimbaud), where the saltimbanque exists in a perpetual state of melancholy and social alienation. In the poems of Guillaume Apollinaire, one of several poets who were among the artist's closest friends at this time, the acrobat acquires an air of mystery and enchantment that clearly corresponds to Picasso's tone. Through paintings, watercolors, gouaches, drawings, and prints, Picasso tends to show his fairground performers at rest, often in domestic settings that are genial and warm. Yet in keeping with their relatively impoverished circumstances and the saltimbanque's traditional role as a symbol of the neglected artist, a pervasive ennui suffuses Rose period pictures.

The paramount work in this series is the large Family of Saltimbanques. Several preliminary studies for this composition exist, and x-radiography shows that Picasso attempted previous versions on the large canvas itself before arriving at the final image. Family of Saltimbanques is a summation of the fairground theme. Set within a desolate landscape, the vagabond troupe embodies a condition of collective alienation, as the figures gather yet fail to interact. The acrobat at the far left, bearing the artist's features, is dressed as Harlequin, a wily character from eighteenth-century popular theater (commedia dell'arte) who would often serve as Picasso's alter ego. An elegiac air also characterizes important paintings from this period that depart from the saltimbanque theme, such as Woman with a Fan and Boy with a Pipe, which reveal a burgeoning classicism in his work.

Family of Saltimbanques, 1905, oil on canvas, Chester Dale Collection © 2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. 1963.10.190

Gósol and After

Picasso was now attracting the attention of new collectors and patrons, including the Americans Gertrude and Leo Stein, who were living in Paris at the time. The first work by Picasso the Steins acquired was Harlequin's Family with an Ape. It was at their apartment that the artist probably met Henri Matisse, whose work they had also begun to collect.

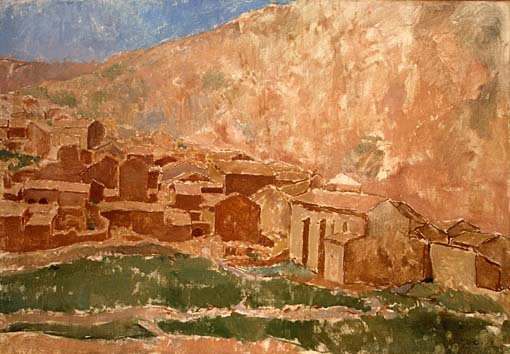

In April 1906 Picasso's fortunes greatly improved when Ambroise Vollard purchased most of his recent work. With finances secure, Picasso was able to travel, and in May he and Fernande left Paris for Spain, where they spent most of the summer in Gósol, a remote mountain village in the Pyrenees. In this rugged yet idyllic setting the artist returned to his Mediterranean roots, producing arcadian depictions of the male and female nude in addition to portraits and views of the sun-drenched hillside village (Gósol Landscape). For his portraits the artist used two somewhat divergent styles: an idealizing manner for weighty but refined images of Fernande; and a grittier, more realistic mode for depictions of Josep Fontdevila, an aging innkeeper with a criminal past who fascinated the artist.

Gósol Landscape, 1906, Private Collection © 1997 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Following his return to the Bateau Lavoir, Picasso continued to explore the new direction his work had taken. In pictures such as Two Nudes he showed female figures of monumental girth standing in an abstract interior space. In addition to ancient Iberian sculpture and Spanish romanesque art, the bathers of Cézanne provided an prominent model for Picasso. The artist now relied on drawing to distill the formal and expressive properties of this new style. Experiments with bronze and ceramic sculpture also played a significant role. While Picasso largely avoided anecdote, his imagery loosely relates to the traditional theme of vanity; common subjects include a woman (usually Fernande) arranging her hair. About this time Picasso also created his most confident and imposing self-portrait to date, portraying himself as something of a latter-day Cézanne.

Two Nudes, 1906, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of G. David Thompson in honor of Alfred H. Barr Jr. © 1997 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Picasso's early career represents less a prologue to the later work than a restless and complex period of experimentation, struggle, and discovery. In this regard, the monumentality of the figures from late 1906 brings the artist's formative years to a conclusion. At the same time, the artist's new treatment of the figure and its ambiguous relationship to pictorial space heralded the emergence of cubism, a movement that would transform the history of twentieth-century art.

Self-Portrait with Palette, 1906, Philadelphia Museum of Art, A. E. Gallatin Collection © 1997 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York