The Darker Side of Light: Arts of Privacy, 1850–1900

Introduction

For most, the art of the late nineteenth century means impressionism, an art of the open air and the café-concert, evoking the pleasures of the landscape and the radiance of Paris, city of light. But there is a less familiar side to the story—a realm of sober contemplation, of recherché, sometimes enigmatic and often melancholy subjects that explore an altogether different dimension of experience. Art of this kind was made for collectors who kept their prints and drawings stored away, compiled in albums and portfolios; who mounted bronze medals in cabinets, placed a statuette on a table in a corner or set it above the shelves in the stillness of the library. These works of art were not an evident part of one's day-to-day environment, like a picture on the parlor wall. Rather, they were subject to more purposeful study on chosen occasions, much like taking a book down from the shelf for quiet enjoyment.

Because prints in particular were handled more discreetly than most works of art, they encouraged the investigation of suggestive, sometimes disturbing subject matter, including complex states of mind and expressions of deep social tension: opium dreams, the obsessions of a lover, the abject despair of an impending suicide, meditations on violence, the fear of death. According to the poet and critic Charles Baudelaire, the technique of etching itself seemed to compel an artist to the most intimate degrees of self-revelation. Because of its association with interiority, the print medium drew the attention of many artistic camps—academic painters, realists, impressionists, and symbolists alike. The desire for private aesthetic experience and the art made to satisfy it constitute an important chapter in a long history of collecting as a secluded endeavor. This representation of prints, drawings, sculptures, and illustrated books seeks to re-create that sensibility.

Auguste Rodin, Figure of a Woman "The Sphinx", model early 1880s, carved 1909, marble, Gift of Eugene and Agnes E. Meyer, 1967.13.6

First published in 1842, the year following the author Bertrand's death, the text is a compilation of fanciful Gothic fables in a romantic mode that later inspired piano compositions by Maurice Ravel.

Félicien Rops, Gaspard de la Nuit, 1868, etching, Rosenwald Collection, 1946.11.189

Adolphe Appian, Pêcheur en Canot, au bord d'une Rivière (Fisherman in a Boat), 1887, etching with monotype on china paper, Gift of Jacob Kainen, 2002.98.371

An inscription added in the fifth state of this print reads:

Here, hanging pitifully you see

Rapacious and lustful birds...

To their kin it is a lesson

That to soar and to steal are not the same…

(Ici, tu vois tristement pendre

Oiseaux pillards et convoiteux...

A leurs pareils c'est pour apprendre

Que voler et voler sont deux...)

Félix Bracquemond, Birds Nailed to a Barn Door (Le haut d'un battant de porte), 1852, etching, State iii/iv, Rosenwald Collection, 1944.8.5

Max Klinger, Siesta I: pl.3, 1879, etching on laid paper, State iv/iv, Gift of the Epstein Family Collection, 2001.132.40

The inscription (trans. Adele M. Holcomb) reads:

Eternal Lust above the city broods,

Insatiable vampire, coveting its food

Charles Meryon, Le stryge (The Vampire), 1853, etching on green paper, State v/x, Gift of R. Horace Gallatin, 1949.1.27

A Walk in Bruges

Phantom city, mummified city, vaguely preserved. It smells of death, of the Middle Ages, Venice, in black, the customary ghosts and the graves...

(Charles Baudelaire, "Pauvre Belgique!" 1864/1866)

Fernand Khnopff, Memory of Flanders: A Canal, c. 1904, conté crayon over graphite, Hearn Family Trust

And when the evening mist clothes the riverside with poetry, as with a veil, and the poor buildings lose themselves in the dim sky, and the tall chimneys become campanili, and the warehouses are palaces in the night, and the whole city hangs in the heavens, and fairyland is before us.

(James McNeill Whistler, "The Ten O'Clock Lecture," London, February 20, 1885)

James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne, 1878, lithotint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.8664

In 1878, in Berlin, the twenty-one-year-old artist exhibited a series of drawings under the title "Fantasies regarding a discovered glove, dedicated to the woman who lost it." The drawings were preliminary studies for this series of etchings, Klinger's most beguiling pictorial essay, which envisions a lover's obsession with a fetish that undergoes a myriad of transformations over the course of ten images.

Klinger meditated for some time about the individual titles and the ordering of the compositions, and pencil annotations on the National Gallery's set of proof impressions record his evolving thoughts on the matter. They indicate, for example, a two-part prelude, followed by a dream sequence culminating with the loss of the glove and the lover's awakening. Although manifestly allegorical, the tragicomic tone of the cycle seems also to have had a basis in the artist's personal experience.

Max Klinger, Abduction (Entführung), 1878/1880, etching and aquatint in black on chine collé, State i/v (proof), Anonymous Gift, 1995.82.9

Edgar Degas, Woman by a Fireplace, 1880/1890, monotype on heavy laid paper, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1985.64.168

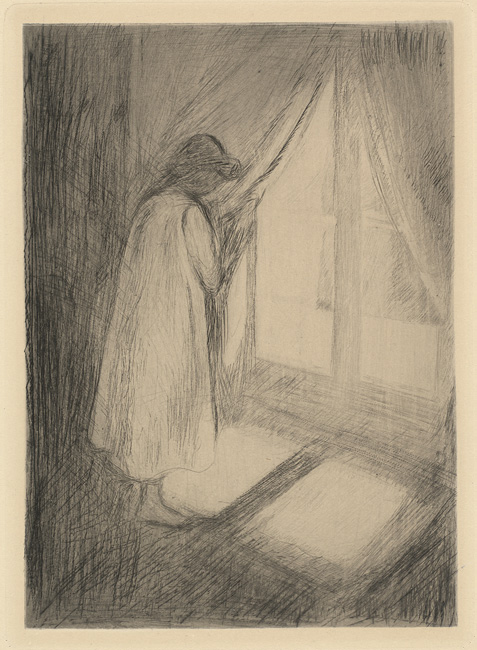

Edvard Munch, Girl at Window (Madchen im Hemd am Fenster), 1894, etching, State v/vi, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.9022

Albert Besnard, Morphine Addicts (Morphinomanes), 1887, etching, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.1480

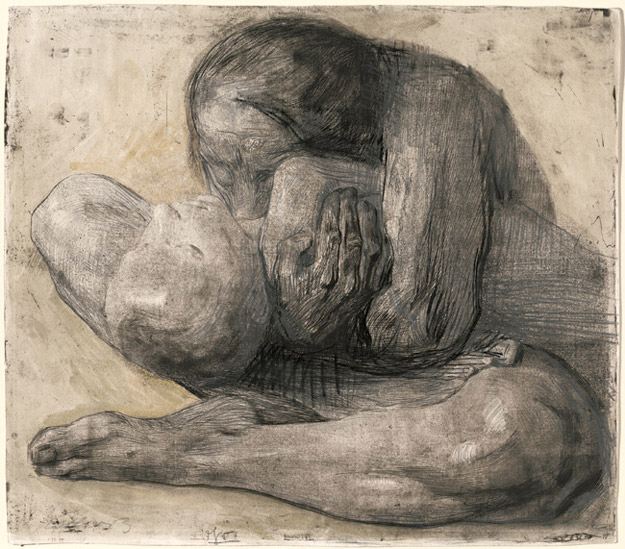

Käthe Kollwitz, Woman with Dead Child (Frau mit totem Kind), 1903, engraving and softground etching retouched with black chalk, graphite, and metallic gold paint on heavy wove paper, State iv/x (trial proof), Gift of Philip and Lynn Straus, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1988.67.1

Also known as La Châtelaine, or the Lady of the Manor, this poster was commissioned as a newspaper advertisement for Jules de Gastyne's novel Le Tocsin (The Alarm or The Omen).

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, The Manor Lady or the Omen (La chatelaine ou le tocsin), 1895, lithograph in turquoise and light blue [poster], State A, Rosenwald Collection, 1952.8.455

Odilon Redon, Cain and Abel, 1886, etching on wove paper, Gift of Ruth Cole Kainen, 2006.57.27

But Catherine had seen: and in spite of herself she screamed, from the heart, surprising even herself as though she had just admitted a preference she didn't even know she had.

"Watch out! He's got a knife!"

(Emile Zola, Germinal, 1885, trans. Roger Pearson)

Käthe Kollwitz, Scene from Germinal (Szene aus Germinal), 1893, etching, State iii/iv, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.5258

This print commemorates the victims of the Paris Commune of 1871, a popular uprising against the provisional French government immediately following the disastrous Franco-Prussian War. The composition suggests that Manet's sympathies lay with the brutally suppressed Communards. Although Manet must have made his sketch for it in 1871, no doubt because of its political sensitivity the lithograph was not published until three years later.

Edouard Manet, Civil War (Guerre civile), 1871, lithograph, State 2nd tirage, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.5758