Toulouse-Lautrec and Montmarte

Montmarte

The art of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901) is inseparable from Montmartre, the working-class district on the outskirts of Paris where the artist lived for most of his career. In the late nineteenth century, Montmartre became the heart of a daring, often racy, entertainment industry that lured thrill-seeking Parisians to its dance halls and cabarets, circuses and brothels. The district was electrified by the unusual mix of people drawn to the quarter: working-class laborers enticed by the inexpensive housing, performers seeking fame and fortune, adventurous Parisians who strayed from the more bourgeois city center, and curious tourists. Cheap rents, along with the licentious culture, also attracted young, avant-garde artists, who reveled in Montmartre’s pleasures. For these artists, the raucous spirit of Montmartre—its unbridled energy, tawdry behavior, garish colors, and provocative celebrities—was both a way to live and a subject to depict.

Set upon a butte, or hill, and removed from the city center, Montmartre had an identity distinct from central Paris. Its rural roots were evident at the end of the century, when working windmills still dotted the landscape. Narrow, winding, and haphazard streets also contrasted Montmartre with central Paris, where Baron Haussmann’s urban modernization plan had created a coherent design with broad avenues and uniform street lamps. Considered a semirural, working-class area, which was not incorporated into the city limits until 1860, Montmartre was unaffected by Haussmann’s urban renewal and consequently retained its character. Montmartre’s separation from central Paris—geographically, demographically, historically, and architecturally—set the stage for the decadent fringe culture that arose in the district on the butte.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Marcelle Lender Dancing the Bolero in "Chilpéric", 1895-1896, oil on canvas, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1990.127.1

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901), the quintessential chronicler of the Parisian district of Montmartre, created some of the most memorable images of the exciting new culture of late nineteenth-century France. After moving to Paris in 1872, Lautrec immersed himself in the culture of the district, painting and drawing by day and dwelling in the cafés and cabarets by night. Working in several ateliers, where he became friendly with other young artists enthralled by the district, Lautrec honed his artistic skills. He soon gained recognition in Montmartre, and when his first poster was pasted on walls all over Paris, he became nearly as famous as the advertised celebrity. Lautrec remained prolific, experimental, and original for the next decade, until his death in 1901 at age thirty-six.

1. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Photograph, National Gallery of Art, Gallery Archives, John Rewald Papers

2. Maurice Guibert, Toulouse-Lautrec Dressed in Japanese Costume, c. 1892, Photograph, National Gallery of Art, Gallery Archives, John Rewald Papers

3. Photograph of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Photograph, National Gallery of Art, Gallery Archives, John Rewald Papers

4. Photograph of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Photograph, National Gallery of Art, Gallery Archives, John Rewald Papers

5. Photograph of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Photograph, National Gallery of Art, Gallery Archives, John Rewald Papers

6. Paul Secau, Toulouse-Lautrec, c. 1892, Photograph, National Gallery of Art, Gallery Archives, John Rewald Papers

7. Anonymous, Toulouse-Lautrec in Jane Avril's Hat and Scarf, c. 1892, Photograph, National Gallery of Art, Gallery Archives, John Rewald Papers

Early Life and Work

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s privileged roots did not make him an obvious fit for the seedy district with which he became associated. The artist was born in the city of Albi, in southern France, into an aristocratic family with ties to the counts of Toulouse, who had once ruled over the Languedoc region of France. His parents were cousins, a common occurrence for wealthy families of the era who were anxious to preserve their lineage. Lautrec suffered the results of inbreeding: abnormally weak bones caused multiple breaks, which stunted his growth and caused him lifelong difficulty with his legs. Barred from many activities, Lautrec became a keen observer, and, with the encouragement of his mother, began drawing and painting in his teenage years.

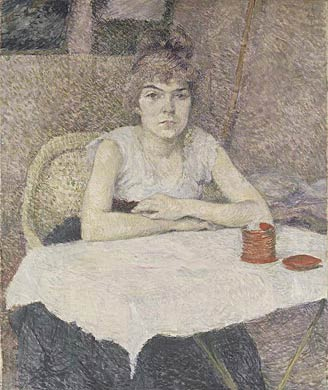

In 1872, Lautrec and his mother moved to Paris, where, a decade later, he began to study art formally. It was at that time, in the early 1880s, that he began to frequent Montmartre, where he painted its denizens, many of whom were his acquaintances or intimates. In Young Woman at a Table, Lautrec depicted the artist, circus performer, and artists’ model Suzanne Valadon, who posed numerous times for him, as well as for his artistic hero, Edgar Degas, and other Montmartre artists. This genre painting of a lower-class woman alone at a café table—a subject popular with Montmartre artists—illustrates Lautrec’s early experimental work; rapid brushstrokes demonstrate a preference for a new freedom of handling, as did the work of Vincent van Gogh, who was then living in Montmartre and whose brother Theo, an art dealer in Paris, purchased this painting.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Young Woman at a Table, “Poudre de riz,” (“Rice Powder”), 1887, oil on canvas, 56 x 46 cm (22 1/16 x 18 1/8 in.), Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

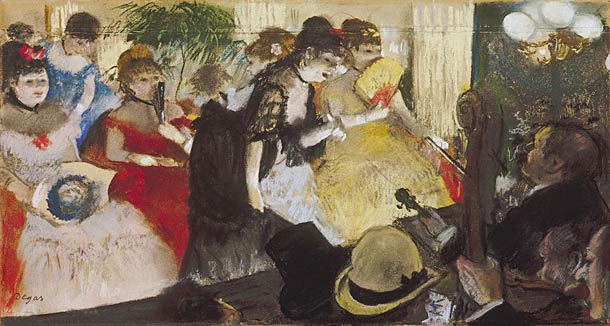

Degas for Dessert

Impressionist painter Edgar Degas’ subject matter, as well as his innovative framing, lighting, and perspectives, greatly influenced Lautrec, although the older artist did not reciprocate the admiration. So taken was Lautrec by Degas’ work that one evening after hosting a lavish dinner party, Lautrec invited his guests out for dessert. Rather than treating them to sweet pastries, he escorted them to a neighbor’s apartment for a private viewing of Degas’ work—a feast for the eyes!

Edgar Degas, Café-Concert, 1876/1877, pastel over monotype on paper and board, 23.5 x 43.2 cm (9 1/4 x 17 in.), Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., William A. Clark Collection

Cafés, Cabarets, and Dance Halls

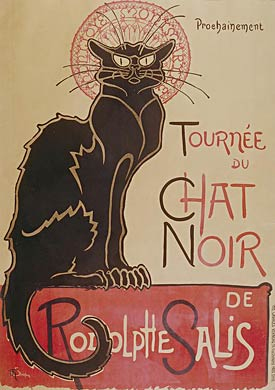

When the artist-cum-entrepreneur Rodolphe Salis died in 1897, the inscription on his tombstone read: “God created the world, Napoleon the Legion of Honor, and I, Montmartre.” While Salis, the owner of the celebrated Chat Noir (Black Cat) cabaret, exaggerated his importance, his epitaph correctly suggests the fundamental role played by the Chat Noir in the development of Montmartre. Salis’ “cabaret-artistique” opened its doors in 1881, and almost immediately became a gathering spot for avant-garde artists, poets, musicians, and writers, who used the cabaret as a sort of artistic laboratory to recite poems, sing chansons, and exhibit paintings. The cabaret’s name, chosen for its multiple associations with sources as diverse as Edgar Allan Poe and French folktales, itself became a leitmotif for the district. Artists regularly used images of the black cat, as in Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen’s poster Tournée du Chat Noir. Steinlen’s poster, with the black cat sitting upright and a halo surrounding its head with the inscription “Montjoye Montmartre,” advertises the Chat Noir cabaret, while conjuring the sensual, mysterious, independent, and nocturnal culture of Montmartre.

Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, Tournée du Chat Noir, 1896, color lithograph, 135.9 x 95.9 cm (53 1/2 x 37 3/4 in.), The Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Gift of Susan Schimmel Goldstein

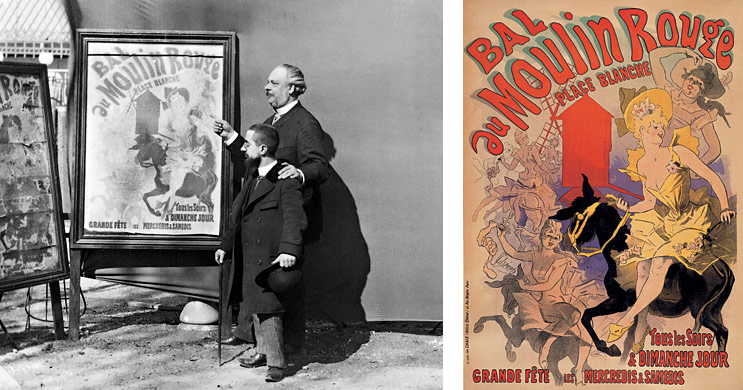

Publicity posters, made possible by the lithographic technique, were an important innovation of the artists of Montmartre. Jules Chéret, considered the father of the modern poster, was a generation older than Lautrec. His posters, with coquettish, beautiful women known as chérettes, conceived of the text as an integral visual component of the overall design and elevated posters to an art form. His 1889 poster Bal du Moulin Rouge depicted voluptuous women who flirted with viewers and beckoned them to the Moulin Rouge dance hall, denoted by the central red windmill.

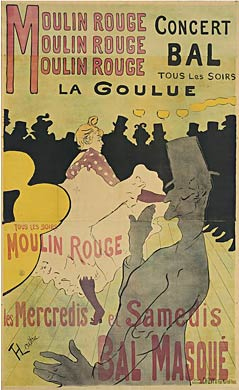

Just two years later, Lautrec was commissioned to create his own poster advertising the Moulin Rouge. The artist’s first foray into the art of lithography was a resounding success: one evening in December 1891, three thousand copies of Lautrec’s Moulin Rouge: La Goulue were pasted on the walls around Paris, prompting an outpouring of popular and critical acclaim and turning the young artist into an overnight sensation. Lautrec’s Moulin Rouge poster was far more daring than the comparatively subdued poster by Chéret. The dance hall’s name is repeated three times in an eye-catching design that then draws the viewer’s eye down to the central motif: La Goulue. Born Louise Weber (1870–1929), La Goulue (the greedy one) was a young dancer who turned the cancan into a risqué dance with high kicks and loud shrieks. Seen here with her dance partner Valentin le Désossé (Valentin the Boneless), the provocative La Goulue attracts a sizable audience, rendered by Lautrec in silhouette form. The unusual use of silhouette was influenced by the flat designs of Japanese art then popular among the avant-garde and also by the Chat Noir’s shadow theater productions, in which zinc cutouts were back-lit and their shadows then projected upon a puppet-theaterlike stage. Innovative designs based on silhouettes were perfectly suited for the bold, graphic style of posters and other works of the era.

Jules Chéret, Bal du Moulin Rouge, 1889, color lithograph, 124.1 x 88 cm (48 7/8 x 34 5/8 in.), Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Kurt J. Wagner, M.D., and C. Kathleen Wagner Collection

One evening in December 1891, about three thousand copies of this poster—Lautrec’s initial foray into lithography—were pasted on walls across Paris. Critics and the general public alike were struck by the poster’s modern sensibility; it includes bold colors, a variety of lettering styles, and innovative use of silhouettes. The poster advertises the Moulin Rouge dance hall and its featured performer La Goulue (the Greedy One or the Glutton), so named for her voracious appetite for all things sensual. By advertising a specific celebrity rather than anonymous beauties, Lautrec infused his poster with star power. The poster created a sensation, and fueled the popularity of both La Goulue and Lautrec.

Despite the fame of this poster, its genesis remains unclear. The owner of the Moulin Rouge, Charles Zidler, may have approached Lautrec directly, or Lautrec may have won a competition. It is also uncertain who first introduced Lautrec to the medium of lithography, although the artist Pierre Bonnard is often mentioned as a possibility. It is known, however, that Lautrec was well aware of the lithograph that Jules Chéret had created as the first poster advertising the Moulin Rouge. Chéret, the so-called “father of the modern poster, depicted anonymous, flirtatious women — known as chérettes—Lautrec’s later, more modern one.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Moulin Rouge: La Goulue, 1891, color lithograph (poster), 191 x 117 cm (75 3/16 x 46 1/16 in.), The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection

In addition to providing the subject for Lautrec’s most famous poster, the Moulin Rouge provided the backdrop for some of Lautrec’s most highly regarded paintings, including At the Moulin Rouge. This dance hall, opened by Charles Zidler and his partner Joseph Oller in late 1889, had a carnival-like atmosphere, with not only dancers but performers of all types, including singers, puppeteers, acrobats, and animal acts. At the Moulin Rouge is an unsettling painting, with severe lighting, unconventional perspective, and an ambiguous narrative. To the right is a figure (thought by some to be the performer May Milton), whose tilting, subaqueous green face draws viewers’ attention. Behind this prominent figure La Goulue can be seen with her back to the viewer, pinning her hair before a mirror. Lautrec himself can be found in the rear of the room, his diminutive figure accompanied by his cousin. The lower left-hand quadrant is dominated by the sharp angle of a balustrade that at once brings the viewer into the dance hall while separating him or her from the café table, where a group of Lautrec’s male friends sit with the entertainers La Macarona and Jane Avril. With its skewed perspective, lurid colors, and perplexing social dynamic, At the Moulin Rouge is both alienating and arresting—an embodiment of the spirit of Montmartre.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge, 1892/1895, oil on canvas, 123 x 141 cm (48 7/16 x 55 1/2 in.), The Art Institute of Chicago, Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection

Stars of Montmarte

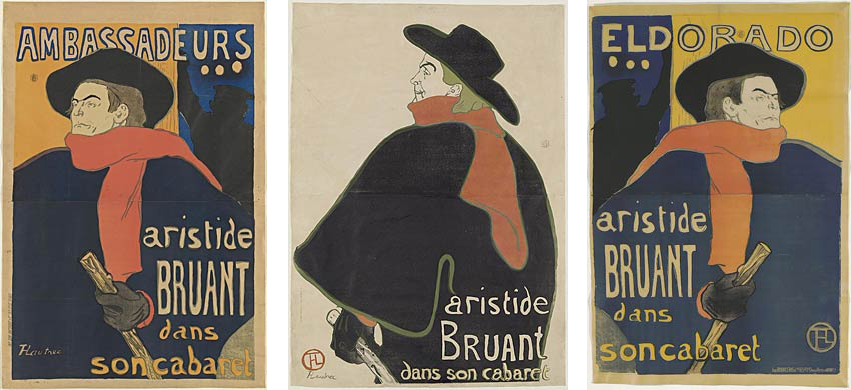

Montmartre in the late nineteenth century witnessed the rise of the modern celebrity. Fueled by the booming entertainment industry and aided by the development of the publicity poster, performers at dance halls, cafés, and cabarets became stars. Of all the performers of Montmartre, perhaps the most famous was Aristide Bruant. The gruff singer and songwriter performed at the Chat Noir, where he sang declamatory songs of working-class misfortunes and hurled insults at his increasingly bourgeois audience who relished his affronts, reveling in the “authentic” working-class experience. When the Chat Noir moved to larger quarters in 1885, Bruant took over the lease of the original location and renamed it the Mirliton (trashy verse). Eventually he became so popular that he was invited to perform at the Ambassadeurs, a café located in central Paris. Bruant commissioned Lautrec to create a poster advertising his appearance at the Ambassadeurs. The artist responded to the invitation with a monumental five-color lithograph printed on two sheets of paper. Designing a poster as bold as its subject, Lautrec distilled the figure of Bruant to his most recognizable features: his signature hat, red scarf, and black cloak, as well as his imposing posture and defiant gaze. Bruant was so taken by Lautrec’s design—“Am I that grand?” he is said to have remarked—that he went on to commission four additional posters from the young artist, all variations of the original.

(left) Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Ambassadeurs: Aristide Bruant, 1892, color lithograph (poster), 139 x 95.2 cm (54 3/4 x 37 1/2 in.), The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection

(middle) Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Aristide Bruant in His Cabaret, 1893, color lithograph, image: 127.3 x 94 cm (50 1/8 x 37 in.), The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection

(right) Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Eldorado: Aristide Bruant, 1892, color lithograph (poster), image: 137.5 x 96.4 cm (54 1/8 x 37 15/16 in.), The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection

In addition to Bruant and La Goulue, performers such as Marcelle Lender, Jane Avril, Yvette Guilbert, Loïe Fuller, May Milton, and May Belfort were popular subjects for Lautrec and his contemporaries. Lautrec periodically developed intense fixations with a single celebrity, whom he would watch obsessively for a period ranging from a single season to several years. The dancer Marcelle Lender first captivated the artist’s attention in 1893, when he began to attend theater regularly, and again two years later, when she appeared in the farcical operetta “Chilpéric.” Lautrec attended her “Chilpéric” performances some twenty times, creating numerous drawings and lithographs. In his painting Marcelle Lender Dancing the Bolero in “Chilpéric” (1895–1896), recognized as one of the most significant of his career for its handling of color and conveyance of energy, the artist depicts Lender center stage dancing the bolero. She thrusts her dark-stockinged leg forward and reveals the bright pink layers of her dress, echoing the black-and pink flowers of her headdress.

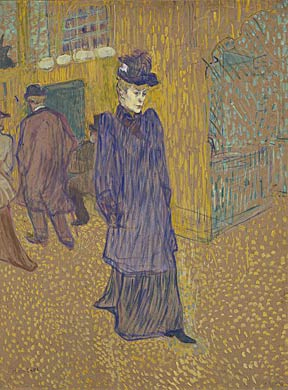

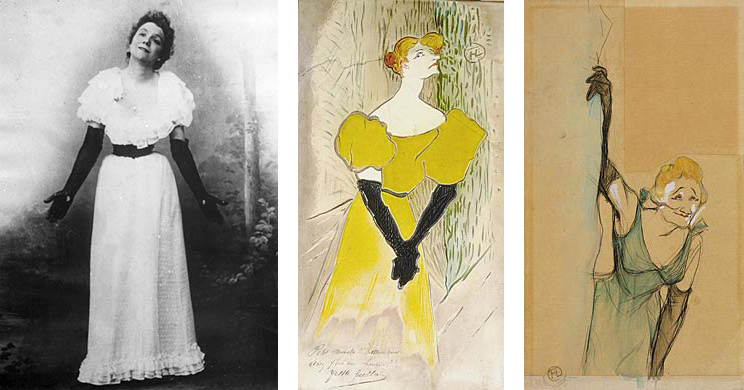

While Lautrec never developed a close relationship with Lender (who remarked, “The frightful man! . . . he indeed loves me. . . . But the painting, you can have it.”), he became close friends with many other performers. Lautrec worked collaboratively with the cabaret singer Yvette Guilbert, producing numerous works in which he caricatured her by exaggerating her lanky figure and facial features, and elongating her trademark black gloves. Of all his celebrity subjects, Lautrec was perhaps closest with Jane Avril, whom he depicted in her public persona as a daring and provocative dancer and as a private, introverted woman.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Leaving the Moulin Rouge, 1892, essence on board, 84.3 x 63.4 cm (33 3/16 x 24 15/16 in.) framed: 105.5 x 83.4 x 10 cm (41 9/16 x 32 13/16 x 3 15/16 in.), Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, Bequest of George A. Gay

Aristide Bruant

The singer and songwriter Aristide Bruant (1851–1925), who performed first at the Chat Noir, and later at his own cabaret Le Mirliton, was the quintessential Montmartre artist. Bruant grew up comfortably in a small village not far from Paris, but when his family fell on difficult times, he was forced to move to Paris to seek employment. Working as a railroad clerk by day, Bruant spent his evenings immersed in the unruly atmosphere of Montmartre, studying the rough vernacular and attitudes of the lower classes. His verses, written in the language of the street, recounted the struggles of those down on their luck. Frequently, Bruant rained insults on his increasingly bourgeois audience, who ironically seemed to revel in the “authentic” working-class experience of Montmartre that Bruant provided.

(left) Aristide Bruant, Photograph, National Gallery of Art, Gallery Archives, John Rewald Papers

(middle) Gravelle, "Tous les Clients sont des Cochons!" ("All the Clients are Pigs!"), cover for Le Mirliton, June 1903, color photorelief, 29.2 x 20 x 4.2 cm (11 1/2 x 7 7/8 x 1 5/8 in.), The Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Herbert D. and Rush Schimmel Museum Library Fund

(right) Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Bruant at the Mirliton, 1893, color lithograph, image: 82.1 x 58.7 cm (32 5/16 x 23 1/8 in.), The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection

Yvette Guilbert

Yvette Guilbert (1867–1944) debuted on stage in 1887 as an actress in a traditional theater in Paris, but she soon moved to Montmartre's more avant-garde performance venues. With her unconventional singing voice, and an unfashionably tall and thin figure, Guilbert was an unlikely star of Montmartre's cafés-concerts. However, her success largely came from her ability to turn these unexceptional qualities into attributes. Rather than singing in a straighforward manner, Guilbert would half-sing, half-speak her ditties, earning her the title of the "diseuse fin de siècle" (end-of-the-century teller). Similarly, rather than concealing her lanky figure, Guilbert wore long black gloves and simple dresses with plunging necklines to exaggerate it, establishing herself as a stand-out from the more buxom performers.

By 1890, Guilbert was appearing regularly at the Moulin Rouge, where she perfected her personal style. Her distinctive performances earned Guilbert great fame and a cult status. She became a favorite subject for artists, including Lautrec, Jules Chéret, Ferdinand Bac, and Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, who captured the singer's sinuous lines in endless media. After making her mark at the Moulin Rouge, Guilbert went on to appear at other Montmartre establishments, including the Divan Japonais and the Ambassadeurs.

(left) Yvette Guilbert, Photograph, National Gallery of Art, Gallery Archives, John Rewald Papers

(middle) Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Yvette Guilbert, 1895, ceramic plaque, 52.07 x 28.26 cm (20 1/2 x 11 1/8 in.), San Diego Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Robert Smart

(right) Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Yvette Guilbert Taking a Bow, 1894, black crayon, watercolor, and oil with white heightening on tracing paper, mounted on cardboard, sheet: 41.75 x 24.13 cm (16 7/16 x 9 1/2 in.), Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Gift of Mrs. Murray S. Danforth

I was looking for an impression of extreme simplicity, which allied itself harmoniously with the lines of my slim body and my small head...I wanted above all to appear highly distinguished, so that I could risk anything, in a repertoire that I had decided would be a ribald one.... To assemble an exhibition of humorous sketches in song, depicting all the indecencies, all the excesses, all the vices of my “contemporaries,” and to enable them to laugh at themselves...that was to be my innovation, my big idea.

— Yvette Guilbert

(left) Leonetto Cappiello, Yvette Guilbert, 1899, polychrome plaster, 34 x 23.5 x 17.4 cm (13 3/8 x 9 1/4 x 6 7/8 in.), The Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Carleton A. Holstrom and Mary Beth Kineke Purchase Fund

(right) Leonetto Cappiello, Yvette Guilbert, 1899, oil on canvas, 116 x 90 cm (45 11/16 x 35 7/16 in.), Musée d'Orsay, Paris; Gift of Mme Monique Cappiello, granddaughter of the artist, 1979

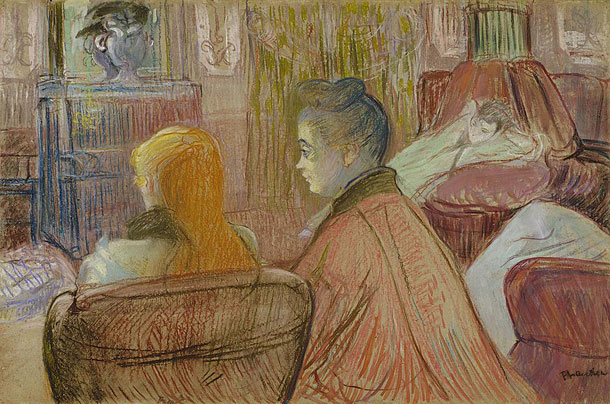

Maisons Closes

While Lautrec’s celebrity images highlight the flamboyant beauty and sexuality of Montmartre, his pictures of the maisons closes—the late nineteenth-century French euphemism for brothels—observe the seamy world of prostitution. The subjects of these works are not famous stars, but rather nameless women whom Lautrec depicts without glamour or sensationalism. In the Salon: The Sofa illustrates a group of prostitutes in a maison close (closed house) seated upon a red divan, awaiting their clients. With resigned faces and tired eyes, modestly cut frocks, and reserved body language, these women engage with neither the viewer nor one another, embodying a world of alienation. Such alienation, a recurring theme in Lautrec’s work, is frequently regarded as a classic symptom of modernity, and more specifically, of Montmartre.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, In the Salon: The Sofa, c. 1892–1893, oil on cardboard, 60 x 80 cm (23 5/8 x 31 1/2 in.), MASP. Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand, São Paulo, Brazil

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, In the Salon, c. 1893, pastel, gouache, oil, pencil, and watercolor on cardboard, 53 x 79.7 cm (20 7/8 x 31 3/8 in.), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection, Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser, 1978

Circuses and Late Work

The circus appealed to Montmartre artists for both its perpetual activity and its outlandish spectacle. The butte's Cirque Fernando, which captured much of the flamboyant energy of the hill, was a popular subject for Lautrec and other artists, including Louis Anquetin, Pierre Bonnard, Henri-Gabriel Ibels, and Théophile Pierre Wagner.

Lautrec's interest in the circus was a logical extension of his childhood paintings and drawings of equestrian scenes. One of his earliest mature works, Equestrienne (At the Circus Fernando), 1887–1888, features the trained horses that were a major circus attraction of the period. The painting, admired for its youthful confidence and brazen sexual overtones, was purchased by the Moulin Rouge's owner to hang in the famous dance hall.

While Lautrec never fully abandoned the subject of the circus in the 1890s, it was not until his 1899 institutionalization that he returned to the subject with full force. Early that year, when the artist's alcoholism had become life threatening, Lautrec was confined against his wishes to a clinic in suburban Paris. Determined to win his release, Lautrec made a series of crayon circus drawings from memory to convince his doctors of the soundness of his mind. Recalling subject matter from his earliest days in Montmartre, the ailing Lautrec's late circus drawings are poignant images that secured his release from the clinic. In the following years, Lautrec's health deteriorated as his alcoholism progressed; he died in the arms of his mother on September 9, 1901, at the age of thirty-six, leaving behind a vivid legacy expressing the spirit of Montmartre.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Equestrienne (At the Circus Fernando), 1887–1888, oil on canvas, 100.3 x 161.3 cm (39 1/2 x 63 1/2 in.), The Art Institute of Chicago, Joseph Winterbotham Collection