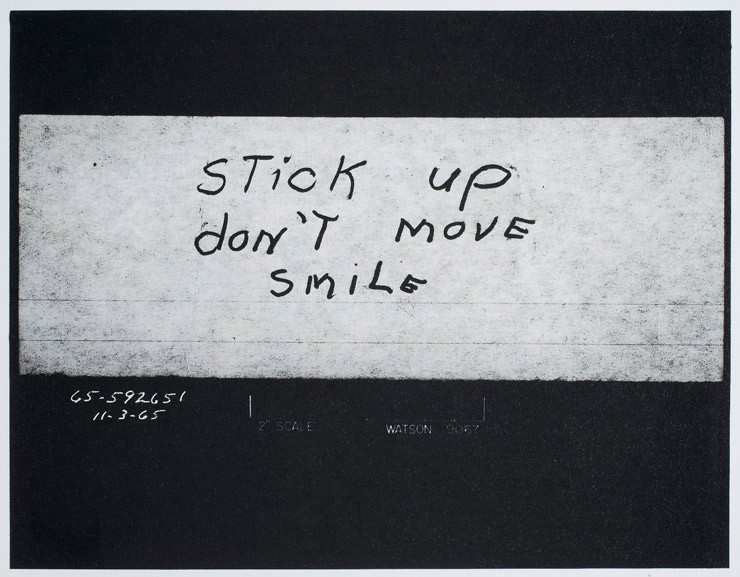

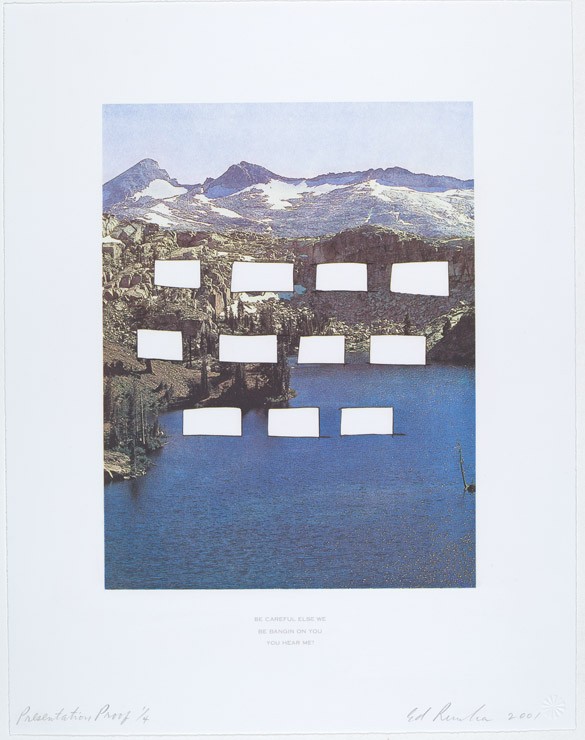

The sequence of blanks in each print in this series corresponds to a menacing message transcribed in the print’s lower margin. Most were invented by Ed Ruscha (American, born 1937), but at least one mimics a note used in a real bank robbery in Los Angeles. Ruscha has long mined the relationship between the meaning and the appearance of words. Or disappearance, in this case. Cityscapes calls to mind the cut-and-paste technique of ransom notes, the redaction of sensitive documents, or the appearance of abstract works of art. The implicit visual correspondence between censored blanks and transcribed words highlights the serial structure of language—meaning is generated through the sequential assemblage of interchangeable components. It also underscores importance of shared reference points for understanding. The word “smile” written on a stick-up note carries a radically different meaning from “smile” said by, say, a photographer. Out of context, Ruscha’s series suggests, language shoots blanks.

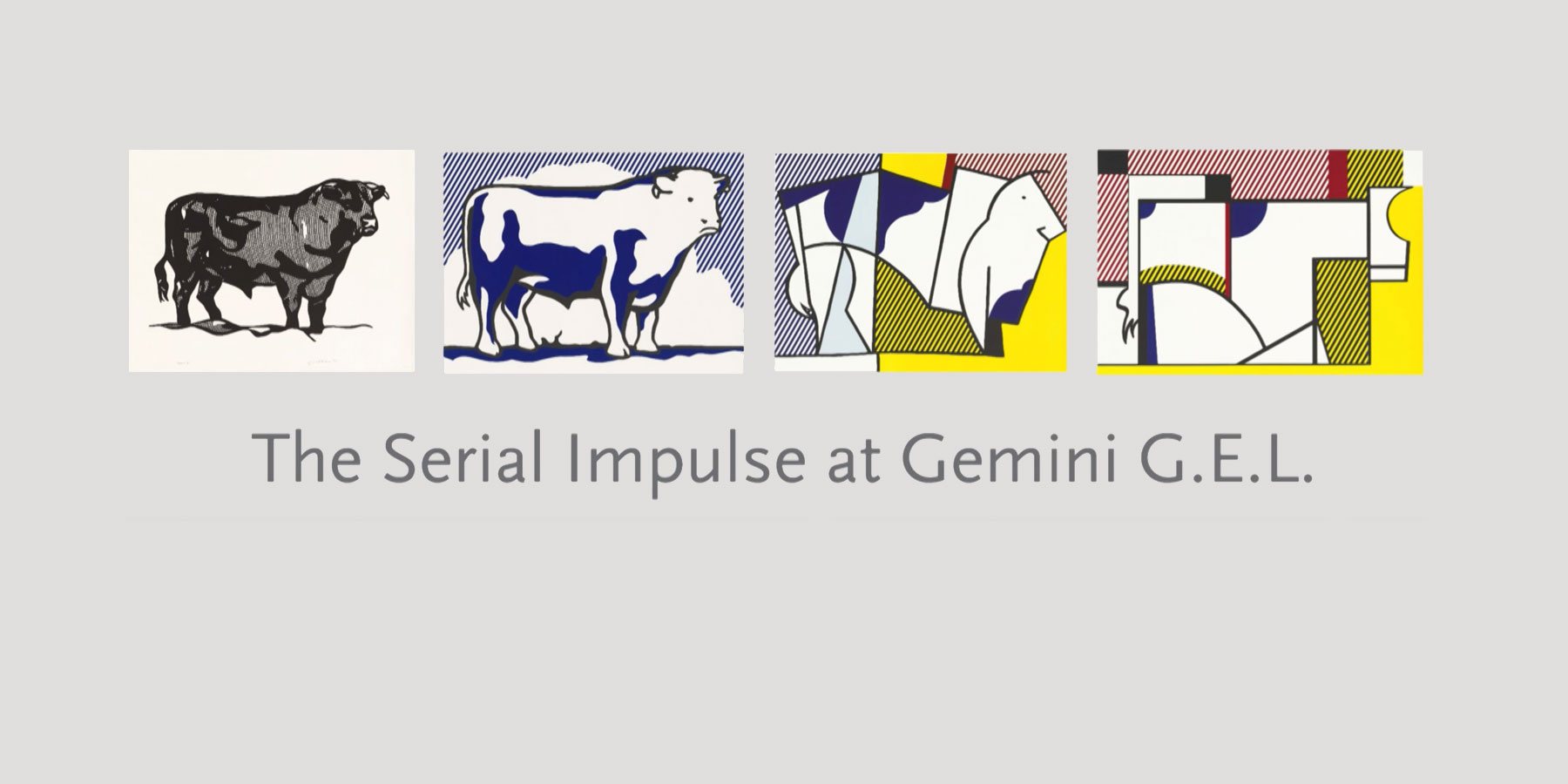

Ed Ruscha, Cityscapes, 2007

Bank robbery note, 1965. Photograph by James Watson, Los Angeles Police Department

“I was very intrigued by [ransom notes’] visual quality, by the fact that they are made with different little cut-out letters. Somehow, these ransom notes, and my interest in ‘censor strips’ and ‘vacancies,’ began to merge into one pictorial element.”—Ruscha, 2012

Ed Ruscha, BE CAREFUL ELSE WE BE BANGIN’ ON YOU, YOU HEAR ME?, 2001 from Country Cityscapes series, photogravure, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Graphicstudio/University of South Florida, 2007

Some of the vernacular words and phrases that make up Ruscha’s visual language are borrowed from his surroundings, complete with idiomatic slang and even misspellings. While the threats spelled out in his titles appear intimidating, they are at times tinged with the unintended humor of idioms and clichés, as in BE CAREFUL ELSE WE BE BANGIN’ ON YOU, YOU HEAR ME? from the related series Country Cityscapes. This ambiguity between menace and humor points to the slippery meaning of words without context. Ruscha first used the title Cityscapes in a mid-1990s group of works in which he applied paint to canvas or bleach to rayon-covered board to suggest censor strips redacting or obscuring language. The use of bleach makes literal a form of linguistic sanitization, or erasure. For Ruscha, the term “cityscape” echoes “soundscape,” the sounds that make up an environment, and alludes to the colloquial use of language in urban contexts (the artist has wryly referred to himself as a landscape painter). His related Country Cityscapes adopt picturesque postcard scenes of the American West to illustrate a more blatant relationship to landscape, but the generic quality of the images is key. “Backgrounds are of no particular character,” Ruscha cautions, as they exist only as “anonymous backdrops for the drama of words.”