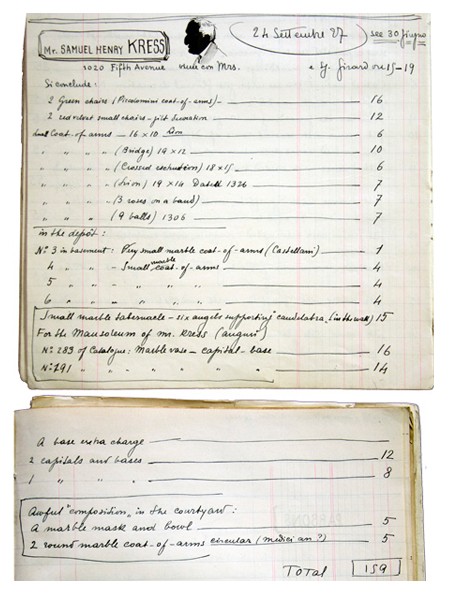

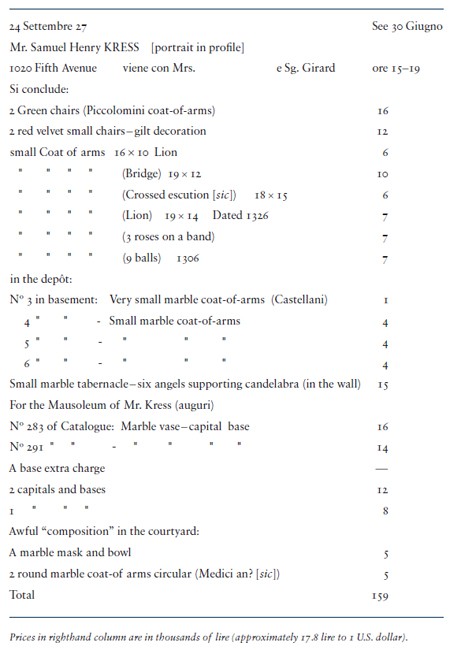

Henry Kress, with his “Mrs” [sic] and a certain “Sig.

Stefano Bardini’s sizable fortune meant that Ugo had spent his youth in good schools, training as an artist and earnestly investing in his equestrian skills. When Kress visited, Ugo was thirty-five years old and still relatively new to the actual transactional aspects of art dealing, since he had probably just begun to learn the business when his father died. Until his own death in 1965, Ugo kept diaries recording the visits of scores of foreigners and Italians who came to shop for art and decorative arts, either for their own collections or for resale. To prepare for return visits, Ugo wrote detailed remarks about each shopper’s taste, noting who accompanied the visitor (either in the role of advisor or as someone acting on commission to bring clients in to visit). Ugo animated his entries by sketching little portrait caricatures of his (largely male) buyers, his pen expressing their faces as well as details of their hats, cravats, eyeglasses, cigars, and other accessories.