Histories of the Cold War in Africa typically position the continent as a site of proxy conflict between superpowers, East and West. They are tales of guns and tanks, not paint, pencils, and photographs; they are rarely tales of African agency. Yet in 1974 the revolution that put Ethiopia firmly on the global map of the Cold War was enacted by domestic agents and driven by images. On September 11 Ethiopian television screens showed a doctored documentary about the unfolding famine in Wollo, north of Addis Ababa. The original film, shot by journalist Jonathan Dimbleby for UK audiences, had been reedited in Addis to include footage of Emperor Haile Selassie’s perceived excesses, from vast state banquets to grossly pampered pets. Watched by thousands throughout the Ethiopian capital, the screening put suffering into jarring juxtaposition with excess as the ultimate indictment of imperial negligence. As journalist Colin Legum reported, that night all were “invited to watch [a] TV spectacle in which the bones of feudal rule were . . . exposed with ruthless professionalism.” The following morning a military delegation arrested the emperor at his palace; his rule had lost all legitimacy.

Accounts of the Ethiopian revolution typically make only brief mention of the screening, characterizing it as a simple final gesture at a point when regime change already appeared inevitable. If histories of the Ethiopian revolution have been written without images, histories of Ethiopian art have similarly neglected the revolutionary period,

I position the documentary screening as the culmination of prolonged pressure from Ethiopia’s students to make “feudalism” visible. At the revolution’s heart was a push to reveal, to lay bare, to demystify. A

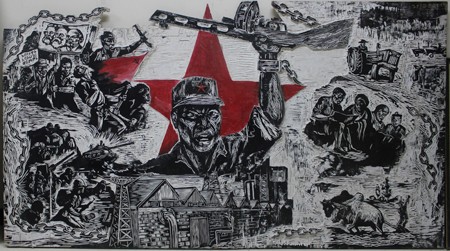

At Addis Ababa’s School of Fine Arts, several months before the screening and coup, student Eshetu Tiruneh painted a mural based on sketches of those amassed on the capital’s outskirts. Entitled Victims of the Famine, it was a defiant gesture, depicting the starving as if they were marching into the school. Although the most explicit, Eshetu’s was not the only such action. Many young artists were engaged in using paint and printmaking to question authority and to make visible that which the emperor appeared to conceal. As my research shows, artists were bound to the movement for change and subsequently became invaluable to the military leaders, who demanded that they visually translate the new official ideology, Marxism- Leninism, for a largely illiterate population.

Across four chapters I examine the fates of photography and film, graphic art, painting, and cultural heritage through the revolutionary years of 1974–1991. Emphasis falls particularly on the first

Seemingly clear, didactic posters, for example, reveal ideological inconsistencies dogging the regime and its detractors, slippages in translation from the greater Communist world, and conspicuous mobilizations of local iconographies. Soviet-trained Ethiopian artist and critic Seyoum Wolde, who had insisted in 1980 that all professional Ethiopian painters should pursue socialist realism, admitted in a 1991 university report that his efforts had failed. More than half of