Art historians of different cultures have for the past century dealt with the issue of the relationship between art and reality. They have provided insights that go beyond cognitive and representational approaches to recognize the evocations, resonances, and empathies between artistic formulations and people’s real-life experiences, often proving the implied boundaries to be blurred or nonexistent. Taking on this perennially thorny problem to question what is “real” in art, my book tackles the notion of

Mid-Ming Suzhou artists’ quests to make the world comprehensible

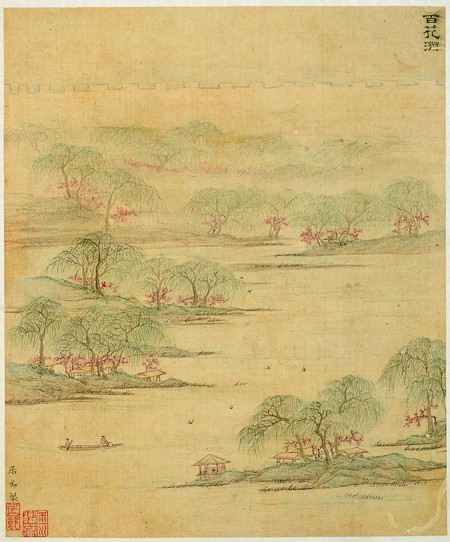

through art led them to seek inspiration from their own living environment. In Suzhou prefecture, in the lower Yangtze Delta, the land was crossed by numerous watercourses, and walkable spaces were connected by thousands of bridges. Thus navigating the physical environment necessitated pause and continuation, and people’s experiences of living in the place regularly involved contingencies and serendipities. As the land was parceled by water, division and connection were dialectical aesthetic measures in Suzhou artists’ pictorial compositions, which resulted in heterogeneous views of a collectively constructed Suzhou landscape. Therefore my book opens by considering the relationship between geo-aesthetics and painting practices and how people’s approach to living in and constructing the real world resonated with artists’ creation of their familiar and lived worlds in paintings. I argue that the artists’ attention to their living environment went beyond topographical representation to the level of

The next two chapters of the book deal respectively with two prominent motifs in mid-Ming Suzhou paintings—the tree and the path—and how they reflected ways of world-making in relation to the human body. Special trees in public sites were thought to bear witness to the histories of places, preserve memories of the past, shelter the community for people’s well-being, and project the prosperity of future descendants. Wen depicted trees as tectonic forms that sheltered human bodies and created treescapes to embody the presence of cosmic forces. In a way similar to trees, paths indicate the presence of the human body, but unlike trees, which connect the ground with the sky, paths delineate and contain spaces on the ground, rendering a sense of the groundedness and the spatiotemporal sustainability of places. I consider the path as both form and process. As a form, the winding path produces infinite expansion of the pictorial space that resonates with the experience of slow walking while being immersed in delightful distractions, an effect that also prolongs the viewer’s empathetic looking at the painting by scrutinizing the details. I argue that the path as a process undergirded the importance of a trajectory of “becoming” in artistic creation, which signaled the literati’s valorization of slowness in the face of an impending economy of speed and efficiency that was then advancing with the growth of commerce and urbanization.

The creation and use of “real scene” paintings for social and communal events (such as birthday celebrations and farewell parties) is the subject of the final chapter of the book. In those cases, artists’ depictions of the experienced (or projected) scenes of the lives of their recipients implied associations between persons and places and between individuals and communities. I conclude that the components of the “real scene” are both life in places and painting as a place for immortalizing life.