Throughout his career Edward Hopper (1882–1967) explored the visual environments of hospitality services, producing paintings, drawings, and illustrations that are as culturally probing as they are formally beguiling. In the 1920s he designed covers for two widely read hotel trade magazines, and from the 1930s through the 1950s he produced several canonical paintings of hotels and related establishments such as motels and tourist homes. The body of hotel work has not attracted prolonged scholarly engagement, yet it merits our attention because it expands and challenges the modernist paradigm of alienation and fragmentation in which Hopper’s art is often situated. Hotels remain sites at once of decorum and detachment. My book in progress argues that Hopper’s paintings capture well these dual sensibilities with suggestions of stasis and flux, as well as of the artistic and the abject.

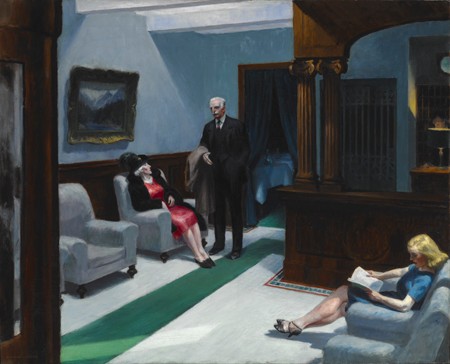

During my fellowship, I wrote a book chapter on Hopper’s painting Hotel Lobby. Examination of the mahogany ornament, floor treatment, desk clerk, and revolving door reveals a painting that, like the standing man who touches the foreshortened strip of carpet, has one foot in the stillness of the past and the other in the dynamism of the present and future. Hotel trade publications had long directed readers’ attention to the decorative potential of flooring, emphasizing carpet as a way to guide foot traffic and determine the placement of furniture. Suggesting a means by which to walk from door to desk, elevator, restaurant, and chairs, the green carpet in Hotel Lobby functions similarly, leading guests and providing part of a grid for optimal furniture placement and ornament. The tapering of the carpet suggests modernist

As much as the carpet and the figures adjacent to it register concerns proper to 1943, the woman and couple are flanked by brown wooden reminders of yesteryear. Buffers of darkness containing the bright colors, the wainscoting at left and the desk at right are like old-school architectural rejoinders to the emphatic present-ness of the lobby’s lighting, flooring, and human denizens. If the wainscoting evokes the rootedness of a loosely defined but still valued past, the framed oil painting on the wall at left ratifies that past-ness. With distance-obscured mountains crowning a gently rolling foreground, which in turn encompasses a watery expanse, the painting possesses the subject matter and maintains the compositional formula of the Hudson River School, especially works such as The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak (1863; Metropolitan Museum of Art), by Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902). The neoclassical detailing of the arch over the desk and its supporting columns designate the antiquated and outmoded. The revolving door cropped at left also contributes to the dialectic sensibility of Hotel Lobby. In the painting and several study drawings, the door is a compositionally stabilizing framing device. Given the intimation of a random but steady stream of anonymous individuals rushing in, however, the image recalls the chaos of a quickly gyrating amusement park turnstile. Part of what makes the position of Hopper’s imagined beholder in Hotel Lobby so unique within the corpus of revolving-door imagery is that he or she is neither facing a swing door nor within the momentarily formed chamber. The revolving door facilitates entrance and exit but could easily trap and cause serious bodily harm—recalling the use of the motif in examples of twentieth-century American film and literature.

Art historians’ characterizations of the clerk range from shadowy to

bordering on sinister. Symbolically caged behind the front desk, most of his body obscured or invisible, the figure might reasonably suggest interpretations of menacing detachment and off-putting disassociation. In the context of urban America circa 1943, the clerk’s inattention to and physical removal from the guests is out of step with well-documented hotel employee etiquette. Lobby denizens might treat the site as either “a haven from the street” or a space in which to “remain anonymous.” Hotel protocol held that, whatever the guest’s behavior in this regard, the clerk should be a model of affability and accessibility. In Hotel Lobby the character’s presence in the murky margins only slightly veils a deft balance between wayward, rebellious absence and helpful, professional presence.