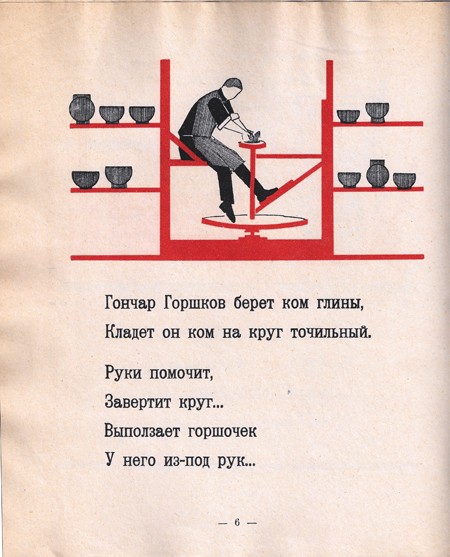

The Soviet regime’s concern with children’s literature gave rise to serious discussion of one of the oldest and most beloved literary genres: the fairy tale. During the 1920s the fairy tale and its place in Soviet children’s literature were among the most highly contested cultural issues of the day. Since many fairy tales were seen as filled with religious superstition and promoting monarchism, many educators and critics felt that it was essentially “criminal” to introduce proletarian children to old morals relevant only to a capitalist society. New Soviet children’s literature, by contrast, was thoroughly rooted in contemporary Soviet reality. Popular themes included industrial and agricultural topics, the class struggle in capitalist countries, the international Communist movement, and the heroic lives of the Communist Party leaders. Aimed at the nation’s youngest readers and essentially constituting the antithesis of the fairy tale, the new genre of the “production book” promoted Soviet social and economic ideals by exploring various professions and trades.

Starting in the late 1920s, the Soviet government’s initial encouragement of artistic experimentation was replaced by the imposition of much stricter control over the arts. In 1935 the Communist Party issued a decree placing all publishing houses under the supervision of the Komsomol (Young Communist League), which established a system of strict censorship over children’s publications and initiated an intense state crackdown on avant- garde experimentation. The government now set new priorities on the rendering of illustrations in a clearly accessible, realistic manner.

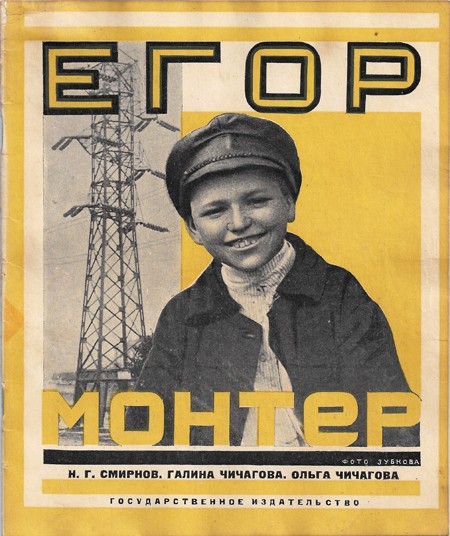

The bulk of my research for “Images for the New Generation” derives from a careful examination of hundreds of Russian illustrated children’s books of the 1920s–1930s. These books are now rare, with only a limited number of copies in existence worldwide. Before my fellowship at CASVA, in conducting my research and locating examples of rare books and mock-ups, I visited many archives and libraries in Russia, Europe, and the United States. During my two-month residency at CASVA, I completed my research in the National Gallery of Art Library and the Library of Congress, where I consulted many publications concerned with pedagogical and sociological issues relevant to children’s literature in Russia. I also revised several chapters of my book. The first chapter, “Does the Proletarian Child Need Fairy Tales? Debates about Children’s Literature in the 1920s–1930s,” demonstrates how children’s literature was subordinated to the educational goals of the new political system. The second chapter, “Molding the ‘New Man’: Educational Experimentalism, Soviet Ideology, and Children’s Literature, 1918–1936,” is devoted to exploring the connection between the new Soviet children’s literature and contemporary developments in Russian and American education and pedagogical theory. Included in this discussion are the writings of John Dewey (1859–1952), which were widely available in Russian translation and influential in Soviet education. “Photography as a Sign of Modernity in Soviet Illustrated Children’s Books,” the third chapter, shows how photo-illustrated books exemplified Russian avant-garde artists’ shift from abstract compositions to works that incorporated documentary elements capable of satisfying the government’s mandate to reach the masses.