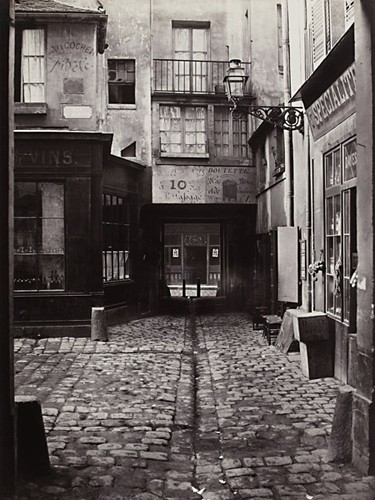

During the political regime known as the Second Empire (1852–1870), Paris underwent a radical transformation from a fetid, congested city with a labyrinthine layout to the most functional, elegant, and alluring capital of Europe. Under the direction of Emperor Napoleon III, urban planner Baron Haussmann launched a massive campaign to restore many of the city’s monuments, to build broad new streets, city squares, and parks, and to install public works and amenities throughout the city. In 1860 the city annexed surrounding areas, expanding from twelve to twenty administrative districts, or arrondissements. The most dramatic expressions of this process, often called Haussmannization, were the percements, or “piercings”: a two-step process that entailed clearing out older, congested (often working-class) quarters and “piercing” them with broad, straight arteries designed to promote the circulation of people, goods, traffic, air, water, and sunlight. Wider streets also made it more difficult to build street barricades—a common resistance tactic used by rioters in the revolutions of 1830 and 1848. As Haussmann recalled in his memoirs, “We ripped open the belly of old Paris, the neighborhood of revolt and barricades, and cut a large opening through the almost impenetrable maze of alleys, piece by piece . . . .”

Many lamented the disembowelment of Old Paris, a beloved place that was celebrated in the art and literature of the time. Even the emperor was cognizant of this loss and in 1860 laid the foundations for a municipal agency devoted to preserving the city’s history. Marville was tasked with documenting the streets of Paris that were slated for demolition. Working methodically, he made more than 425 photographs of the threatened streets and buildings. Although some of the streets Marville photographed still exist (not all the planned demolitions were executed), in other cases these photographs remain the only records of the appearance of streets that had been part of the city for centuries. The power of the Old Paris album, as this group of photographs has come to be known, lies both in its historical significance and in the extraordinary compositions and dazzling detail of the prints themselves.