Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain

Painted by Alonso Berruguete’s talented father, Pedro, this exquisite scene of the Virgin and Child shows the enduring influence of Flemish painting on the arts of Castile. Berruguete must have started his career in command of a similar style of painting — now called the Hispano-Flemish style.

Pedro Berruguete, The Virgin and Child Enthroned, c. 1500, oil on panel, Ayuntamiento de Madrid, Museo de San Isidro, Los Orígenes de Madrid. Image: © Photographic Archive, Museo Nacional del Prado

This is one of only a handful of paintings that survive from Berruguete’s time in Italy. It depicts Salome, who ordered Saint John the Baptist’s beheading. Here she holds his head on a silver platter. Her long fingers, elegant pose, demure gaze, and idealized features are consistent with mannerism, a style of art that was becoming fashionable in Florence during the 1510s. Berruguete was in the vanguard of the movement. Like other mannerist artists, he favored exaggerated forms and complicated poses over the restrained beauty of earlier Renaissance art.

Alonso Berruguete, Salome, c. 1514–1517, oil on panel, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence. Image: Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence

Alonso Berruguete, Saint Matthew Writing the Gospel, from the retablo mayor (high altarpiece) of San Benito el Real, 1526/1533, oil on panel, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Vallodolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain); photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor; CE0271/003

Alonso Berruguete, Relief with Putti, from the retablo mayor (high altarpiece) of San Benito el Real, 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain); photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor; CE0271/072

This is one of four reliefs from the retablo mayor of San Benito depicting scenes from the life of Saint Benedict. Here Benedict is shown converting a heretic who had been trying to rob a poor farmer. The man falls, terrified, from his horse as he watches Benedict perform a miracle.

Alonso Berruguete, Saint Benedict Converting the Goth Zalla, from the retablo mayor (high altarpiece) of San Benito el Real, 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain); photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor; CE0271/005

Doubtless seen by Berruguete during one of his visits to northern Castile, this exquisite statuette of Saint James the Greater originally decorated Gil de Siloe’s masterwork in alabaster, the tomb of King John II of Castile and Queen Isabella of Portugal in the Carthusian monastery of Miraflores, near Burgos. The complex pattern of angular drapery folds, attention to minute details, and elongated bodily features are characteristic of the late Gothic style brought to Castile during the fifteenth century by northern artists like Gil.

Gil de Siloe, Saint James the Greater, 1489/1493, alabaster with paint and gilding, Lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection, 1969, 69.88

Painted wood sculpture was the norm in Castile long before Berruguete’s time, as seen in this group executed in a traditional style that reflects the influence of sculpture from northern Europe.

Spanish (Castile), The Miracle of the Palm Tree on the Flight to Egypt, c. 1490–1510, painted walnut with gilding, Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1938, 38.184

This moving relief was likely carved in Barcelona around 1519, the year Berruguete visited the city. Executed by Bartolomé Ordóñez, a sculptor who, like Berruguete, was from Castile and had worked in Italy, it reflects the shallow carving style of Donatello, the great Florentine master of the fifteenth century. The relief is a reminder that Berruguete was not the only Spanish artist introducing the lessons of the Italian Renaissance to Spain. Ordóñez’s influence was limited, however, as he died the following year.

Bartolomé Ordóñez, The Lamentation of Christ, c. 1518–1519, walnut, private collection

This is Berruguete’s earliest surviving sculpture, which comes from a monastic church near Valladolid, the town in central Castile where the artist moved in 1522. Depicting the bound and tortured Christ as he is presented to jeering crowds on the way to his crucifixion, the figure is likely to have stood on an altar, perhaps as the central figure in a retablo (altarpiece). Berruguete’s treatment of the subject was unconventional in Castile. Instead of following tradition and covering Christ’s body with scourge marks and blood, Berruguete elicits sympathy from the viewer through other means. The cross-legged pose, slender limbs, and unsupported arms create a sense of unbalance that conveys Christ’s helplessness. The solution reflects works of art that Berruguete would have studied in Italy.

Alonso Berruguete, Ecce Homo, c. 1524, painted wood with gilding and silvering, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain); photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor; CE0728

Alonso Berruguete, Saint Christopher, from the retablo mayor (high altarpiece) of San Benito el Real, 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain); photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor; CE0271/015

One of Berruguete’s most celebrated sculptures, this group depicts the moment when Abraham is about to sacrifice his son Isaac on God’s orders. As the anguished Abraham looks heavenward in disbelief, his terrified son kneels and awaits his fate. Before Abraham could carry out the act, however, God appeared and offered him a ram to sacrifice instead.

Alonso Berruguete, The Sacrifice of Isaac, from the retablo mayor (high altarpiece) of San Benito el Real, 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain); photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor; CE0271/013

Alonso Berruguete, Saint John the Evangelist (Calvary group), from the retablo mayor (high altarpiece) of San Benito el Real, 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain); photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor; CE0271/051

Alonso Berruguete, The Virgin Mary (Calvary group), from the retablo mayor (high altarpiece) of San Benito el Real, 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain); photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor; CE0271/050

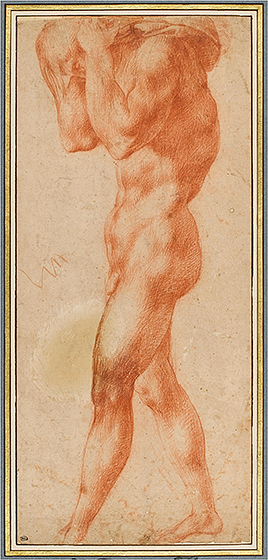

Alonso Berruguete, Man Carrying a Sack, c. 1508–1510, red chalk, Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts graphiques, Paris, Inv. 2706. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

In Rome, Berruguete was granted permission to study Michelangelo’s recently completed ceiling in the Sistine Chapel, as evidenced by this study of the prophet Daniel. It is among the earliest drawings of a single figure from the ceiling. A later inscription on a strip added to the top of the sheet records Berruguete’s name, profession, fame, and visit to Rome.

Alonso Berruguete, The Prophet Daniel (after Michelangelo), c. 1512–1517, red chalk, Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia, Colección Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Carlos, 2453

Alonso Berruguete, Job or Levi, after c. 1525, pen and brown ink, The Art Institute of Chicago, The Leonora Hall Gurley Memorial Collection, 1922.50

Alonso Berruguete, Seven Figures and a Design for Architecture, c. 1540–1555, pen and brown ink and wash with white highlights over black chalk, Beaux-Arts de Paris, EBA 473. © Beaux-Arts de Paris, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Photo by Legs Armand-Valton