Expressing the Individual

Examine Charles Bird King’s Poor Artist’s Cupboard closely and the story of an artist will begin to emerge. “C. Palette” is his or her name, and things don’t seem to be going very well for him or her. Clues appear in book titles like Miseries of Life and Advantages of Poverty, as well as in the meager meal of bread and notice of a sheriff’s sale.

King lived in Philadelphia for four years and only sold two paintings during that time. He was independently wealthy, so scholars believe this painting is meant as a commentary on the lack of support for artists in Philadelphia generally. At times, though, King posed as if he were poor—sleeping on the floor instead of a bed or eating sparse meals.

Why do you think King might have pretended to be poor? What other details can you find that tell us more about the “poor artist” of this painting? How are artists and the arts in general supported today in your school, community, and country?

Charles Bird King, Poor Artist's Cupboard, c. 1815, oil on wood, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, Gallery Fund and exchange), 2014.79.24

Berlin Abstraction is one in a series of paintings Marsden Hartley called the War Motifs. They contain heavily coded expressions of Hartley’s life in Berlin’s vibrant LGBTQ community, the role of the German military in that culture, and an outpouring of the artist’s thoughts about war.

Hartley created the paintings after his close friend (and likely lover) Lieutenant Karl von Freyburg died in World War I. In a way, this painting is a portrait of Freyburg and Hartley’s relationship. Multiple details allude to Freyburg:

· the number 4 in the painting references the Fourth Regiment, in which Freyburg fought;

· the red-and-white checkerboard references Freyburg’s love of chess; and

· the black cross encircled by red and white is an abstracted version of the Iron Cross, a military honor posthumously awarded to Freyburg.

Other colors and symbols refer to aspects of German culture and military pageantry.

How would you visually represent the loss of a loved one? What references to them and their community might you include?

Marsden Hartley, Berlin Abstraction, 1914/1915, oil on canvas, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, Gallery Fund), 2014.79.21

Awa Tsireh (San Ildefonso Pueblo) is one of many Pueblo artists whose works were popular in the early 20th century. Tsireh typically painted figures related to Pueblo traditions and ceremonies, such as these kossa—sacred clowns associated with Tewa-speaking Pueblos. Sacred clowns entertain Pueblo ceremonial participants and they are also, as one scholar writes, “key to cosmic regeneration, they promote healing and fertility, they encourage harmony, and they enforce social control.”

Tsireh painted sacred clowns, distinguished from other figures by black and white stripes on their bodies and clothing, more frequently than other Pueblo artists at the time. It may have been his way of resisting efforts by the Office of Indian Affairs in the 1920s to ban dances and dismantle Native cultures in general. Tsireh helped preserve Pueblo culture and knowledge by omitting or altering details in his paintings for non-Pueblos, never revealing too much to those outside the community.

Some scholars see works by Tsireh and other Pueblo artists as examples of “survivance,” referring to American Indian acts of survival, resistance, and endurance. Why do you think this term might have come into use? What wonderings do you have about Awa Tsireh?

Learn more about Pueblo cultures:

Youth and Teacher Resources, Hopi Cultural Preservation Office

“Reporter's Notebook: Hopi Sacred Objects Returned Home,” NPR News

Awa Tsireh, Two Kossa, c. 1925, brush and black ink with watercolor over graphite on wove paper, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Amelia E. White), 2015.19.381

James Castle created art from the time he was a child growing up in a small town in Idaho. He used found and homemade materials for his works, including cardboard, paper, and soot mixed with saliva to make an inklike solution.

Castle was born profoundly deaf. He attended and lived at the Gooding School for the Deaf and Blind from 1910 to 1915, but he lost most of his practical ability to communicate after he left school. It’s unknown to what extent he could read or write, but he made art for much of his life.

Castle often drew from memory or observed what was around him. What do you notice about the work he created here? What does his life story make you think about?

James Castle, Untitled (Figures Lined Against a Wall), n.d., color wash and soot on found paper, Gift of James Castle Collection and Archive, and Acquisition with Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund, 2013.33.33

Walker Evans captured these women on film while on assignment for Fortune magazine in 1941. He completed the assignment by spending a single hour in downtown Bridgeport, Connecticut, photographing passersby on a June day. In a prior series of photographs the artist hid his camera as he documented New York City subway passengers. In the Bridgeport series, many pedestrians stared at Evans, who hoped his camera, visible to all, could serve as an objective recording device.

What expressions do you detect on the faces of these women? Consider the choices Evans made as an artist. Do you think it’s possible that he was completely objective in photographing them?

Walker Evans, Bridgeport, Connecticut, 1941, gelatin silver print, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harry Lunn, Jr., in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1990.110.12

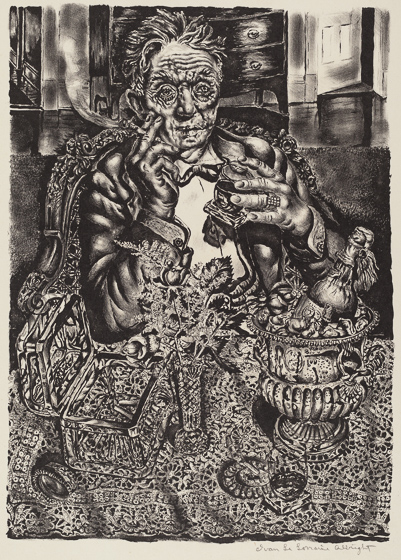

Ivan Albright’s most famous painting, now housed at the Art Institute of Chicago, is one he created for the 1943 film adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. In Wilde’s novel, Dorian Gray trades his soul to stay young and beautiful as he lives a self-indulgent life of vice. His crimes are seen only in a portrait of Gray, which grows more ugly and deformed as Gray’s corruption deepens.

The film’s director selected Albright to paint the film’s portrait of Dorian Gray because of the artist’s meticulous, obsessive technique and complex style, on view here in a self-portrait from 1947. Examine the textures and objects you see: what do you think this self-portrait says about how Albright saw himself?

See Albright’s Picture of Dorian Gray.

Ivan Albright, George C. Miller, Associated American Artists, Self Portrait at 55 East Division Street, 1947, lithograph in black on wove paper, Gift of John Nichols Estabrook and Dorothy Coogan Estabrook, 1987.41.1

After the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, US government officials became worried that Japanese Americans would commit acts of treason or sabotage. The US decided to imprison over 100,000 Japanese Americans—more than half of them US citizens—in internment camps in the western half of the country for the duration of World War II.

Ruth Asawa and her family were among these Japanese Americans. Asawa spent 18 months in the camps, until she received a Quaker scholarship to attend college in 1943 in Wisconsin to become an art teacher. However, because she was prohibited from teaching as a Japanese American, she did not complete her degree. She moved to North Carolina to study art at Black Mountain College and then pursued a career in art and education in California.

Asawa made this printed portrait of her father, Umakichi, in 1965. Umakichi was arrested by the FBI in 1942, when Asawa was in high school. At the time he was a 60-year-old farmer who had been a US resident for 40 years. Asawa did not see her father again until 1948. How does Asawa depict her father here? Why do you think she might have chosen to show his face in the way she does?

Ruth Asawa, Umakichi, 1965, lithograph (stone) in black on white Arches paper, Gift of Dorothy J. and Benjamin B. Smith, 1983.18.190

Diane Arbus’s photographs have long been a source of controversy and criticism. Some critics assert she exploited her subjects, many of whom were outsiders to mainstream society, like this man partially dressed in drag. Others see her works as brave and innovative. When this photograph was first exhibited in the 1960s at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, museum staff wiped spit off its glass surface many times.

Look closely at the photograph. How has the man altered his appearance and features to appear more stereotypically feminine? Given what you see, how do you think he felt being photographed by Arbus? (Arbus always asked for permission to photograph and reproduce images of her subjects.)

Diane Arbus, A Young Man in Curlers at Home on West 20th Street, N.Y.C., 1966, gelatin silver print, Gift of the Collectors Committee, 1994.78.1

Examine this man’s pose, posture, and clothing. How would you describe his personality based upon what you see?

Barkley Hendricks made African American and Latino people the subjects of his portraits beginning in the 1960s. He painted himself, friends, family members, colleagues, and others from his neighborhood—anyone with “distinctive style, personality, and attitude that caught his attention and inspired a creative response.” Hendricks painted portraits even as they had fallen out of favor in the mainstream art world. His works celebrated black and brown bodies and directly addressed the absence of positive portrayals of black people in art history.

The man shown here, Sir Charles, was a “small-time New Haven drug dealer” Hendricks encountered while living in New Haven, Connecticut. Why do you think portraits like this might have been seen as political during the 1970s? Why might Hendricks have chosen to show Sir Charles from three different perspectives?

Barkley Leonnard Hendricks, Sir Charles, Alias Willie Harris, 1972, oil on canvas, William C. Whitney Foundation, 1973.19.1

Ana Mendieta and Christina Ramberg shared an interest in studying and depicting the female body. In Mendieta’s Silueta (silhouette) series, she created silhouettes from natural materials in the shape of her body and then photographed the work before it disappeared back into the earth. Mendieta fled Cuba as a 12-year-old with her sister; they lived in US refugee camps and foster homes for two years before they were reunited with family members. Her work makes sense of this traumatic experience as she reconnects with her Cuban heritage through physical and spiritual means.

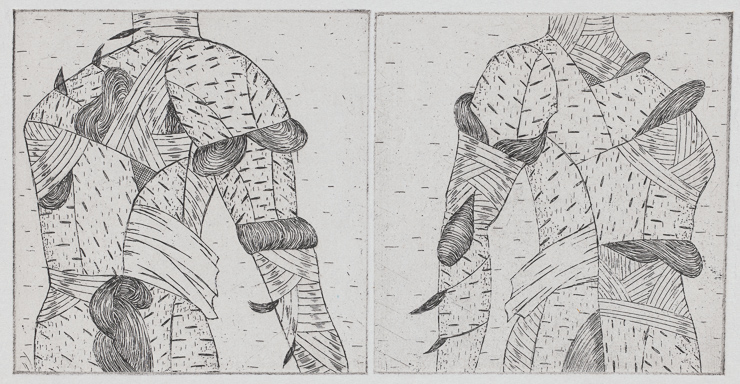

Christina Ramberg’s depictions of fragmented torsos and hips, often bound or corseted, recall the hourglass silhouettes of women in the 1940s and 1950s. Critics also see violent, playful, or sadomasochistic references in her work.

Compare this work with Christina Ramberg's representation of the female body: what’s similar and what’s different? What do you think these works say about women together? Look deeper into second wave feminism: would you consider these artists or their works feminist?

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Silueta series), 1977–1978, gelatin silver print, Gift of the Collectors Committee, 2007.2.2

Ana Mendieta and Christina Ramberg shared an interest in studying and depicting the female body. In Mendieta’s Silueta (silhouette) series, she created silhouettes from natural materials in the shape of her body and then photographed the work before it disappeared back into the earth. Mendieta fled Cuba as a 12-year-old with her sister; they lived in US refugee camps and foster homes for two years before they were reunited with family members. Her work makes sense of this traumatic experience as she reconnects with her Cuban heritage through physical and spiritual means.

Christina Ramberg’s depictions of fragmented torsos and hips, often bound or corseted, recall the hourglass silhouettes of women in the 1940s and 1950s. Critics also see violent, playful, or sadomasochistic references in her work.

Compare this work with Ana Mendieta's representation of the female body: what’s similar and what’s different? What do you think these works say about women together? Look deeper into second wave feminism: would you consider these artists or their works feminist?

Christina Ramberg, Back-to-Back, 1973, etching in black on wove paper, Gift of the Collectors Committee, 2015.158.2

In the 1970s Lee Krasner rediscovered some of her old charcoal drawings of figures. She decided to use them to create collages, once again changing her style of artmaking as she had done repeatedly throughout her career.

Krasner consistently fought for recognition in a male-dominated art world. She wanted to be seen simply as an artist, not a woman artist. Her work does not hint at or reveal her gender.

Examine the overall structure and patterns of Imperative. Where do you see traces of figures? What adjectives would you use to describe this work of art?

Lee Krasner, Imperative, 1976, oil, charcoal, and paper on canvas, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene Victor Thaw, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1991.59.1

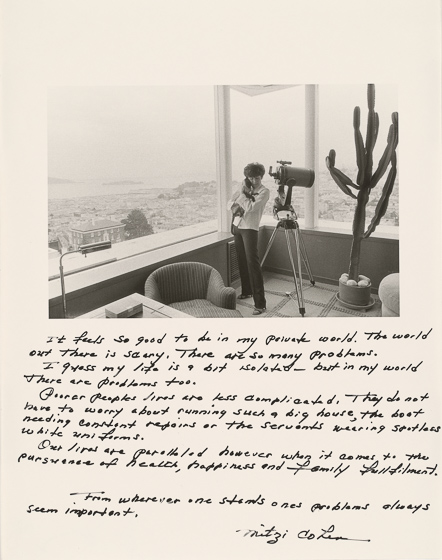

In the late 1970s and early 1980s Jim Goldberg photographed hundreds of rich and poor residents of San Francisco. He initially focused his efforts on residents who were living temporarily in hotels, but expanded his project to include members of his art school’s Board of Trustees.

As part of the process, Goldberg interviewed his subjects, who then wrote their text in their own hands to accompany the finished prints. Goldberg helped shape the commentary, ultimately serving as both photographer and editor. Throughout the project he confronted his own stereotypes and perceptions, and he wrote in a 1985 publication about the empathy, frustration, hope, and powerlessness he felt during the course of the project. Since then many critics have pointed out that the same inequalities between the rich and poor remain today.

Why do you think Goldberg included text written by his subjects on the photographic prints? What impact would the works have without the text? What stories do Goldberg’s works tell, and what reactions do you have to the people he shows?

Jim Goldberg, Mary and Wayne, from Rich and Poor, 1979, gelatin silver print, Corcoran Collection (Gift of the Artist), 2015.19.4478

In the late 1970s and early 1980s Jim Goldberg photographed hundreds of rich and poor residents of San Francisco. He initially focused his efforts on residents who were living temporarily in hotels, but expanded his project to include members of his art school’s Board of Trustees.

As part of the process, Goldberg interviewed his subjects, who then wrote their text in their own hands to accompany the finished prints. Goldberg helped shape the commentary, ultimately serving as both photographer and editor. Throughout the project he confronted his own stereotypes and perceptions, and he wrote in a 1985 publication about the empathy, frustration, hope, and powerlessness he felt during the course of the project. Since then many critics have pointed out that the same inequalities between the rich and poor remain today.

Why do you think Goldberg included text written by his subjects on the photographic prints? What impact would the works have without the text? What stories do Goldberg’s works tell, and what reactions do you have to the people he shows?

Jim Goldberg, Mitzi Cohen, from Rich and Poor, 1981, gelatin silver print, Corcoran Collection (Gift of the Artist), 2015.19.4480

This self-portrait is from artist Saul Steinberg’s sketchbook. Best known for his insightful, inventive drawings and cartoons created for the New Yorker magazine, Steinberg worked in a variety of media and his work is now owned by galleries and museums around the world.

Steinberg referred to himself as a “writer who draws.” Look closely at this self-portrait. How does this sketch reflect ideas, or even a story, about Steinberg?

Dive deeper into self-portraiture by doing this activity inspired by Andy Warhol’s work.

Saul Steinberg, Self-Portrait, Drawing, c. 1986/1995, black felt-tip pen on wove paper in spiral-bound sketchbook, Gift of The Saul Steinberg Foundation, 2016.143.35.22

Like today’s personal social media accounts, family photo albums typically present positive, cheerful moments in the life of a family, obscuring or omitting any troubling or shameful events. Clarissa Sligh decided to mine her family photo album and reconsider events from her childhood in 1950s segregated Arlington, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, DC. She Sucked Her Thumb is from the resulting series of works called Reframing the Past.

What emotions and questions does this work of art raise for you? Consider the ways in which you present your life online or through other outlets.

Clarissa Sligh, She Sucked Her Thumb, 1989, cyanotype, Corcoran Collection (Gift of the Friends of the Corcoran Gallery of Art), 2015.19.4483

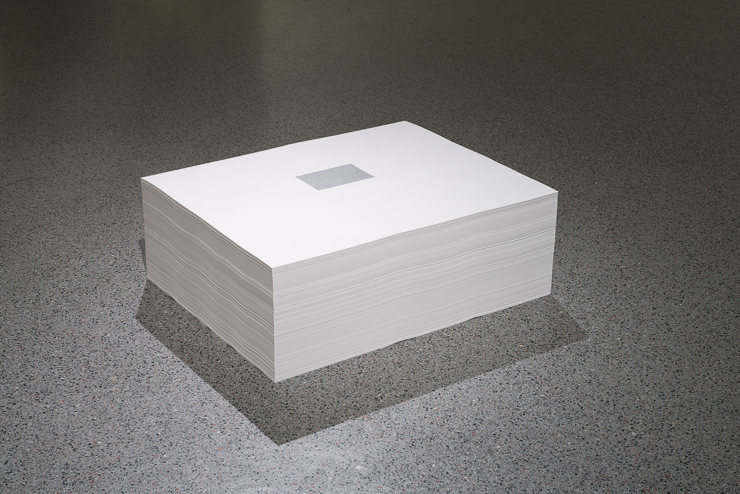

Have you ever lost someone close to you? How did you make sense of your grief and loss?

This work’s title refers to Ross Laycock, the partner of artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Laycock died from an AIDS-related illness in 1991, as did Gonzalez-Torres five years later.

Like much of Gonzalez-Torres’s work, “Untitled” (Ross in L.A.) is minimal, conceptual, political, and participatory. Visitors are invited to take a piece of paper from the stack, slowly diminishing the pile of paper. Both the artist and the museum relinquish control of the work as sheets upon sheets are dispersed to individuals. There’s no way to predict how quickly the stack will change, what will happen to the sheets of paper after they’re taken, or how people will think of them. Eventually, the museum replenishes the stack and the work begins anew.

Consider the stack of paper as a stand-in for Ross’s life or Gonzalez-Torres’s relationship with him. How might this work of art be an allegory of love and loss?

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, "Untitled" (Ross in L.A.), 1991, print on paper, endless supply, Gift of the Collectors Committee and Emily and Mitchell Rales, 2017.51.1

Each panel in Synecdoche represents the skin tone of an individual: sometimes one of artist Byron Kim’s friends, family members, colleagues, or neighbors, and sometimes a stranger. The work functions both as a group portrait and as a collection of simply painted panels in a minimal range of colors. Kim first began the work in 1991 and still adds panels from time to time. The word “synecdoche” is defined as a figure of speech in which a part of something stands in for the whole, or vice versa.

Many viewers understand this work of art to be a political statement on race and the construct of race in the United States. What do you think this work might say about race and identity? What can you learn about the individual sitters in this work of art? How is it similar to or different from a traditional portrait?

Byron Kim, Synecdoche, 1991–present, oil and wax on lauan plywood, birch plywood, and plywood, Richard S. Zeisler Fund, 2009.39.1.1-560

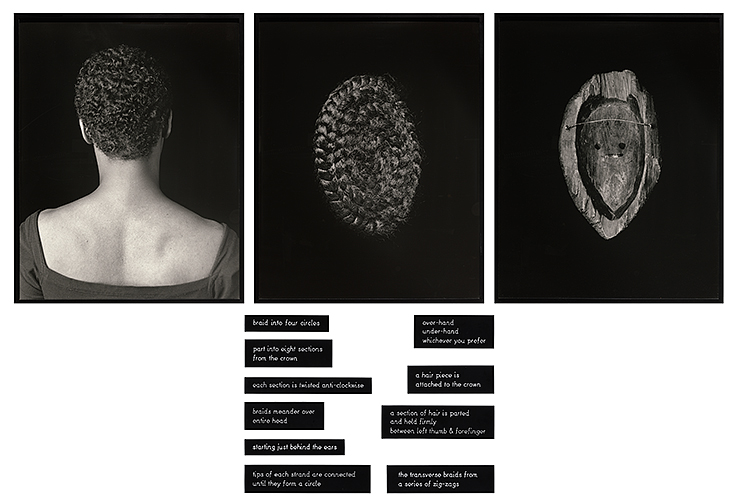

How you style your hair hints at how you see yourself and your identity. For African American women, hair care is a weighty subject that relates to notions of beauty, politics, culture, and history.

Lorna Simpson’s Coiffure touches upon these themes. From left to right the images depict a woman whose hair is cut short, to a circle of braided hair, to the back of an African mask. Simpson links African American hair to African rituals by depicting an actual connection link between the two images in the form of a braid. The text below provides instructions for braiding hair.

Simpson photographed both the woman and the mask from behind, concealing their faces. Why do you think she might have done that?

What is your hair care ritual? How is it tied to your culture or identity?

Lorna Simpson, Coiffure, 1991, 3 gelatin silver prints and 10 engraved plastic plaques, Corcoran Collection (Gift of the Women's Committee of the Corcoran Gallery of Art), 2015.19.4459

How much of your personal life do you reveal to others? How do you choose to share it?

Nan Goldin has unapologetically photographed herself and those around her since she was a teenager in Boston. Relationships, drug use, addiction, violence, loss, and love all feature in her incredibly personal work. In Relapse/Detox Grid Goldin documents her relapse into heroin use and subsequent detox at a location in Connecticut. A boyfriend identified as David H. is seen in the photographs, and Goldin appears in the upper and lower left.

What strikes you about these photographs? What kinds of ethical dilemmas do these photographs raise for you?

Nan Goldin, Relapse/Detox Grid, 1998–2000, 9 silver dye bleach prints, printed 2000, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase with funds donated by the FRIENDS of the Corcoran Gallery of Art), 2015.19.4709

On the right, a yellowed image shows a young man standing in a field, hat in hand, next to a bag containing a recent harvest. On the left a list of handwritten words and acronyms inscribed on the back of the image provides clues and context for the image. The text reads:

92

Angola, Louisiana

L.S.P. [Louisiana State Penitentiary]

Troy West

d.o.c.# [Department of Corrections number] 311719

d.o.b. [date of birth] 5.16.72

p.o.b. [place of birth] New Orleans

entered L.S.P. 1995

Camp C

work line 1

photo 6.11.99

Artist Deborah Luster photographed inmate Troy West at Louisiana State Penitentiary, commonly called Angola, on June 11, 1999. West was one of over 1,000 inmates Luster photographed at three different prisons in Louisiana as part of the series One Big Self. Luster encouraged her subjects to pose as they wished, incorporating objects or a background of their own choosing. Subjects received small wallet-sized reproductions they could share with friends or family members.

Examine the photograph of Troy West. What do you think this photograph says about him? What do you wonder about West?

In an essay she wrote about the project Luster notes that the US incarcerates more of its population than any other country in the free world, and that at the time of her essay “eighty-eight percent of the men who are incarcerated at Angola will die there.”

What does this information make you think about? Why do you think Luster might have titled this project One Big Self?

Hear Luster speak about the beginning of the project and about a few of the individuals she photographed.

Deborah Luster, Troy West, Angola, Louisiana, June 11, 1999, gelatin silver print on aluminum, Gift of Julia J. Norrell, in Honor of Claude Simard and the 25th Anniversary of Photography at the National Gallery of Art, 2014.177.3

May Flowers is part of a larger project by Carrie Mae Weems called May Days Long Forgotten. May Day has a dual meaning here: it is the traditional celebration of spring in some cultures of the northern hemisphere, when children would dance around a maypole, as well as the celebration of International Workers’ Day, instituted in honor of the Haymarket affair of 1886 in Chicago.

Weems has given a nod to the spring celebration by photographing girls dressed in flowers posing outside. She has also used a circular frame to hearken back to the Renaissance, when this format was utilized for images of the Christian Madonna and child. However, instead of showing a mother and child, Weems chose to depict African American girls, one of whom stares out at the viewer.

Weems consistently investigates issues related to gender, race, power, and history in her works. What artistic choices did she make here? Why do you think she featured African American girls in this photo?

Carrie Mae Weems, May Flowers, 2002, chromogenic print, printed 2013, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund, 2014.3.1, © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

John Willis first visited Pine Ridge Reservation, home to Oglala Lakota American Indians, in 1992. He returned regularly for years to visit friends, but has shared his hesitations about documenting residents as a non-Native photographer:

“Knowing the critical debates, which arise with photographers entering the lives of indigenous people living under less fortunate circumstances, has made it difficult to allow myself to exhibit the images I make on the Rez. . . . Among all the poverty and hardship I am drawn by the humble nature and sincere kindness of these proud people. I find visiting them valuable and rejuvenating, for me it is rejuvenating as a reminder of what is really important in life.”

Willis began to publicly exhibit the works after a Native friend suggested he use the photographs to help family and people at Pine Ridge.

How do you relate to the people shown here? How do you think Willis’s photographs might be helping Oglala Lakota?

John Willis, Pine Ridge, 2004, gelatin silver print, Gift of Jeanne and Richard S. Press, 2015.130.4

Rozeal created this painting after learning about the 1990s trend of ganguro, in which young Japanese women began wearing long nails, dying their hair blonde, and applying makeup to darken their skin tone. The artist recalled, “I said, what? Why? I read further, and they were enamored with hip hop. So I said, oh! Hip hop made it to Japan (This is 1997). That’s amazing! Wait. They’re darkening their skin? That sucks. That’s terrible. Why are they doing that? Don’t they know how hard it is to be dark on this planet?”

In response Rozeal made a work that raises questions about cultural appropriation, code switching, agency, and beauty. afro.died, T. is a mash-up of hip hop, classical Japanese Kabuki theater, and Japanese ukiyo-e imagery. Rozeal’s mom took her to a Japanese Kabuki performance when she was a child, and the imagery created by all-male casts stuck with the artist. “Back and forth” written in the background of the painting recalls a 1994 Aaliyah song, “Back & Forth,” as well as the idea of switching between cultures or “codes.” The woman’s over-the-top appearance and dress reference depictions of women in hip hop culture and “female beauties” favored by artists working in 18th-century Edo, Japan. The woman’s makeup references the ganguro trend, as well as blackface, the application of makeup by non-black performers to appear black. Read aloud, the title of the work sounds out “Aphrodite,” the Greek goddess of love and beauty, but in written form it mentions the death of an afro.

What’s beautiful to you? What does this work of art make you think about women in your own community and culture? Who might you want to be in dialogue with to better understand this painting?

Rozeal (formerly known as iona rozeal brown), afro.died, T., 2011, acrylic, pen, ink, marker, and graphite on birch plywood panel, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase with funds provided by the Women's Committee of the Corcoran Gallery of Art), 2015.19.243