Gauguin: Maker of Myth

Mythic Artist

Outspoken, charismatic, and ferociously egotistical, Gauguin enlisted all of his talents in the careful construction of a potent self-mythology. Often spun from a kernel of truth, Gauguin's tales about himself were marked by exaggeration and fabrication. His numerous self-portraits were part of an effort to craft a public image, as well as a means of understanding himself and his role in the world.

Central to Gauguin's mythology was his identification as a "savage," understood by him to mean wild, free, and primitive. He claimed to be of Inca descent, saying, "You know I have Indian blood, Inca blood in me, and it's reflected in everything I do.... I try to confront rotten civilization with something more natural, based on savagery." Gauguin did spend his early childhood in Peru, where his great-uncle had been the Spanish viceroy. But his claim of ancestral ties to the native population held no truth, revealing more about his personality than his biography.

In his self-portraits, Gauguin presented himself as both a prophet and a martyr. In one painting, he is Lucifer, the fallen angel; in another he is Christ, the outsider suffering on behalf of humanity. He saw himself on the margins of society, a wanderer, outlaw, and observer, a heroic artist seeking deeper truths.

(top left) Bonjour Monsieur Gauguin (detail), 1889, oil on canvas glued onto wood, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, The Armand Hammer Collection, Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation

(top right) Self-Portrait (detail), 1889, oil on wood, Chester Dale Collection, 1963.10.150

(bottom left) Christ in the Garden of Olives (detail), 1889, oil on canvas, Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, Gift of Elizabeth C. Norton

(bottom right) Self-Portrait with Manao tupapau (detail), 1893–1894, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Gauguin presents himself as a wandering artist who encounters a peasant woman. He had spent the last several years moving about: since 1885 he had lived in Copenhagen (his wife, Mette, was Danish), Paris, Brittany, Panama, Martinique, and Arles. In Arles he stayed with Vincent van Gogh, and together they visited Montpellier, where they saw Gustave Courbet's painting Bonjour Monsieur Courbet (1854), the inspiration for the title and subject of this painting.

Bonjour Monsieur Gauguin, 1889, oil on canvas glued onto wood, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, The Armand Hammer Collection, Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation

This self-portrait was painted as one of a pair; the second picture is a portrait of Gauguin's friend, the Dutch artist Meijer de Haan. The two were painted on doors flanking a fireplace in the dining room at the inn where the artists were then lodging in Brittany. In this painting, Gauguin represents himself as deeply divided, at once innocent and sinful. The halo suggests an angel, and is echoed by the swaths of golden yellow below, resembling wings, while the snake between his fingers and the tantalizing apples evoke temptation and the fall of man.

Self-Portrait, 1889, oil on wood, Chester Dale Collection, 1963.10.150

In 1889 Gauguin gave his own features to this depiction of Christ on the eve of his Crucifixion, seated within a landscape of drooping olive trees that echo his own weary posture. The struggling artist said about this work, "There I have painted my own portrait... but it also represents the crushing of an ideal, and a pain that is both divine and human. Jesus is totally abandoned; his disciples are leaving him, in a setting as sad as his soul."

Christ in the Garden of Olives, 1889, oil on canvas, Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, Gift of Elizabeth C. Norton

The yellow and green background of this self-portrait echoes the colors of Gauguin's Paris studio, where he painted this picture in late 1893, shortly after returning from his first sojourn to Tahiti. The artist's thoughts, however, still lingered on his past two years in Polynesia, as evidenced by the colorful blue and yellow cloth seen over his left shoulder and the picture on the wall (also on view in the exhibition), Manao tupapau, which features a Tahitian girl.

Self-Portrait with Manao tupapau, 1893–1894, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Sacred Myths

Gauguin was compelled by a lifelong quest for spiritual enrichment and believed in the universality of religion. His first artistic exploration of religious themes was in Brittany, a rural province in northwest France where Christian and Celtic traditions intertwined. Gauguin's paintings of Breton worshippers count among his most formally innovative canvases. The clearly outlined, flat shapes and bold patches of unnatural color represent a movement away from reality and toward abstraction to evoke states of mind.

When Gauguin arrived in Tahiti in 1891 he discovered that European missionaries had successfully converted much of the population to Christianity and the traditional religion of the island was rapidly vanishing. Through his art he attempted to resurrect the lost religion, depicting Oceanic deities and creating idol-like sculptures. Faced with little surviving evidence of their appearance, Gauguin looked to religious imagery from other cultures — especially Hinduism and Buddhism — for guidance. Gauguin, however, never lost sight of the Christian stories, frequently transposing them to Polynesian settings.

(top left) Vision of the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel), 1888, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

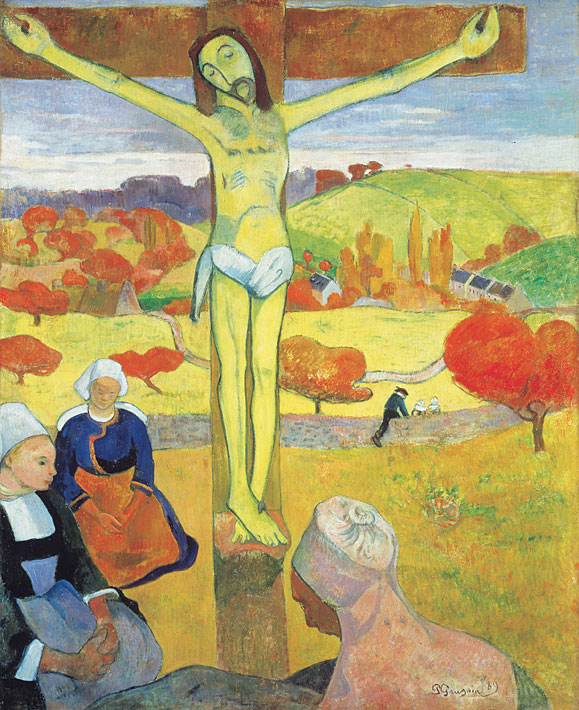

(top right) The Yellow Christ, 1889, oil on canvas, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, General Purchase Funds, 1946

(bottom left) Parahi te Marae (There Lie the Temple Grounds), 1892, oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Rodolphe Meyer de Schauensee, 1980

(bottom right) Hina and Fatu, c. 1892, carved tamanu wood, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Gift from the Volunteer Committee Fund, 1980

Gauguin recognized this painting as a significant breakthrough toward a more imaginary style that moved painting away from naturalism. The picture shows a group of Breton women witnessing a scene from Genesis, in which Jacob is locked in violent struggle with an angel. A large tree trunk divides the canvas into two parts: the real world of the women and the visionary, supernatural world of Jacob and the angel, painted against a brilliant red background. As Gauguin explained in a letter to Vincent van Gogh, "For me in this picture the landscape and the struggle exist only in the imagination of the people in prayer inspired by the sermon, which is why there is a contrast between the life-size people, who are natural, and the struggle in its non-natural, disproportionate landscape."

Vision of the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel), 1888, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

The Yellow Christ was inspired by a polychromed crucifix that Gauguin saw in a Breton chapel. Gauguin's painting brings the wood sculpture outdoors and heightens the palette, coloring the Christ figure an acid yellow and placing him in a prismatic autumnal landscape. The seasonal choice for the painting was likely influenced by local Breton belief, which associated the Crucifixion with the fall harvest and the Resurrection with springtime renewal.

The Yellow Christ, 1889, oil on canvas, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, General Purchase Funds, 1946

Gauguin's efforts to conjure lost Polynesian religious practices sprang largely from his imagination. The dark and imposing sculpture before the mountain, for instance, did not exist in Tahiti, and instead resembles statues found on Easter Island, which Gauguin knew from illustrations. The ornamental fence was inspired by the design of a small Marquesan ear ornament, which the artist then enlarged and embellished with grim skulls hinting at the ritual human sacrifices that took place at the temple grounds — a tradition that had died out as a result of missionary and colonial influence.

Parahi te Marae (There Lie the Temple Grounds), 1892, oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Rodolphe Meyer de Schauensee, 1980

Gauguin carved numerous tiki-like devotional sculptures based on Tahitian deities. Here the goddess of the moon, Hina, is seen with her hand raised, speaking to her son Fatu, god of the earth. While the two deities did, in fact, exist in Tahitian mythology, their appearance is wholly of Gauguin's imagination.

Hina and Fatu, c. 1892, carved tamanu wood, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Gift from the Volunteer Committee Fund, 1980

Earthly Paradise

Gauguin continued the Western tradition of yearning for both the Paradise of biblical literature and the Arcadia of classical antiquity. He believed that the way forward in art was by looking back at more primitive societies, which he dreamed of as places of light-filled warmth, abundance, love, and sexual freedom — a dream designed in direct counterpoint to what he perceived as the overly commercial, decadent, modern Europe. A five-month stay in Martinique in 1887 provided Gauguin his first opportunity to paint in the tropics. In Paris two years later, he was enthralled by the exhibits of non-Western cultures at the World's Fair, where pavilions dedicated to Java, Tahiti, Cambodia, and Tonkin (Vietnam) further fueled his desire for another journey. He dreamed of a tropical paradise, writing rapturously to a friend: “...in a winterless sky, on marvelously fertile soil, the Tahitian just has to raise his arms up to gather his food... for them, to live is to sing and love.”

In June of 1891, Gauguin finally arrived in Tahiti (then a French colony) and began producing images of native women, many of which celebrated a healthy, unrestrained sensuality, free from notions of shame and guilt. Scenes of physical labor and contemporary colonial culture are generally absent from Gauguin's oeuvre, promoting a timeless world of quiet languor. Aside from a two-year return to France (1893 – 1895), Gauguin would spend the rest of his life in Polynesia, living mostly in Tahiti before retreating to the more remote Marquesas Islands.

(top left) Fatata te Miti (By the Sea), 1892, oil on canvas, Chester Dale Collection, 1963.10.149

(top right) Two Tahitian Women, 1899, oil on canvas, Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of William Church Osborn, 1949

(bottom left) Noa Noa (Fragrant, Fragrant), 1894/1895, woodcut printed in yellow, yellow-brown, red and black by Louis Roy, Rosenwald Collection, 1950.17.83

(bottom right) No te aha oe riri (Why Are You Angry?), 1896, oil on canvas, The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection

The naked bathers ensconced in the tropical setting hint at the Tahitian paradise of Gauguin's imagination — a lush world filled with natural beauty and freedom. The artist applies color without restraint, much as he depicts the women shedding their pareos without concern for the eye of the artist or the approaching fisherman seen at the top of the canvas.

Fatata te Miti (By the Sea), 1892, oil on canvas, Chester Dale Collection, 1963.10.149

Using rich, tropical hues, Gauguin painted two Tahitian women bearing offerings of fruit or flowers. Their calm demeanor and quiet beauty recalls Gauguin's admiration for Polynesians, about whom he remarked, "Always this silence. I understand why [they] can remain... for hours, days at a time without saying a word.... It seems to me that all the turmoil that is life in Europe no longer exists."

Two Tahitian Women, 1899, oil on canvas, Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of William Church Osborn, 1949

This print is from a series of 10 woodcuts Gauguin produced on returning to Paris after his first Tahitian trip. They were meant to accompany a text he had begun in Tahiti titled Noa Noa, or "Fragrant," a free-form journal based on his memory, readings, and rich imagination. The prints explore many of the same themes Gauguin addressed in his paintings, with motifs appearing and reappearing as echoes of his obsessions. The prints were never joined with the text and the intended sequence, if there is one, remains unclear.

Although it was his first time working with the medium, Gauguin carved the blocks with great assurance. Initially all prints were made in black and white, but he later collaborated with artist Louis Roy to produce a colored set of the prints, as seen here.

Noa Noa (Fragrant, Fragrant), 1894/1895, woodcut printed in yellow, yellow-brown, red and black by Louis Roy, Rosenwald Collection, 1950.17.83

Devising his titles was an important part of Gauguin's creative process, particularly when they were painted onto the canvas

or carved into the object. He chose Tahitian titles to conjure a remote, exotic world for Western ears and to add a sense of mystery. Several of his Tahitian paintings are titled with questions, perhaps fragments of conversation between the figures that hint at small dramas played out between them, without ever fully explaining their meaning.

Gauguin's grasp of the Tahitian language, however, was patchy at best. His Tahitian titles are often ungrammatical and his occasional translations of them into French were frequently inaccurate, yet give a sense of his intended meaning.

No te aha oe riri (Why Are You Angry?), 1896, oil on canvas, The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection

Paradise Lost

Immediately upon his arrival in the Tahitian capital of Papeete, Gauguin was confronted with the reality of a culture dramatically changed by colonialism. His paintings and writings expressed his sense of loss for the mythical paradise that he did not find. The ancient culture that he had dreamed of had been, by his account, hopelessly diluted, corrupted and erased by Christian missionaries and Western colonization. "The Tahitian soil," he wrote, "is becoming completely French and little by little the old order will disappear."

Gauguin saw the loss of paradise as emblematic of humanity's fall from grace. The figure of Eve and universal sin were recurring themes that the artist explored first in Brittany and later in Polynesia where he depicted the story of Eve in a tropical setting.

(top left) Arii Matamoe (The Royal End), 1892, oil on coarse fabric, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

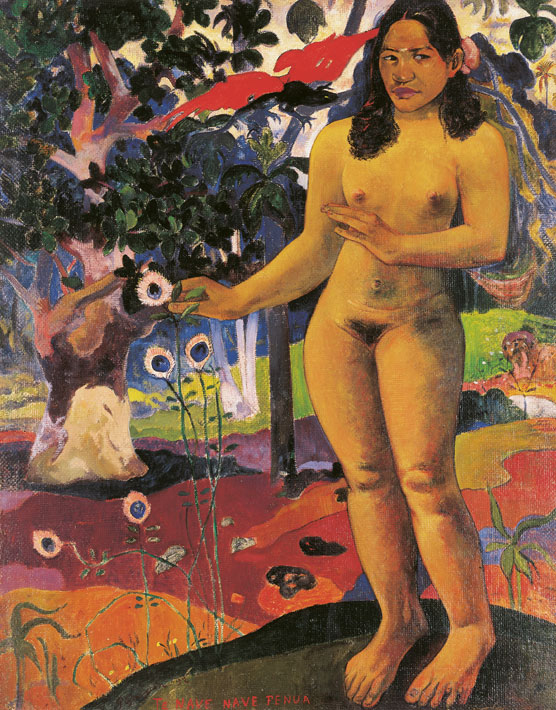

(top right) Te Nave Nave Fenua (The Delightful Land), 1892, oil on canvas, Ohara Museum of Art, Okayama

(bottom left) Parau na te Varua ino (Words of the Devil), 1892, oil on canvas, Gift of the W. Averell Harriman Foundation in memory of Marie N. Harriman, 1972.9.12

(bottom right) Manao tupapau (The Spirit of the Dead Keeps Watch), 1892, oil on burlap mounted on canvas, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, A. Conger Goodyear Collection, 1965

Tahitian for sleeping eyes, matamoe also means death; arii refers to the ancient noble line of native chieftans. When Gauguin exhibited the painting in Paris, he offered the French title La fin royale (The Royal End). Both the Tahitian and French titles suggest that the painting was a response to the passing of the last of the Tahitian kings, Pomare V, who died within days of Gauguin's arrival in the Tahitian capital of Papeete. The severed head is Gauguin's invention — perhaps an allusion to John the Baptist — as Pomare was not decapitated. For Gauguin, Pomare's death symbolized the loss of Tahitian culture in the wake of French colonialism. "There was one king less," he observed, "and with him disappeared the last remains of Maori customs. It was well and truly over, nothing left but civilized people. I was sad: to have come so far..."

Arii Matamoe (The Royal End), 1892, oil on coarse fabric, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Gauguin owned photographs of the sculpted frieze from the Buddhist temple of Borobudur on the Indonesian island of Java. He appropriated the pose of the central figure in the frieze for that of Eve, whom he set in a tropical Eden. Gauguin made several changes to accommodate the Tahitian setting: the tempter appears as a winged lizard, and the apple offered to Eve in Western images of the Fall has been transformed into a beautiful flower (neither snakes nor apple trees exist in Tahiti).

Te Nave Nave Fenua (The Delightful Land), 1892, oil on canvas, Ohara Museum of Art, Okayama

Gauguin transposes the temptation of Eve to Tahiti with significant alterations. The figure of Eve hides her nakedness in shame, echoing Western depictions, but the tempter — usually a snake — here takes the form of a kneeling figure with a masklike face, perhaps the varua ino or evil spirit referred to in the title. In the preparatory pastel he first envisioned this evil spirit as a sinister hooded figure. It was from this full-scale study that Gauguin transferred the design, with minor adjustments onto the canvas. The odd orange and green face that looms in the upper right corner of the painting may be another such spirit. The "words" of the title perhaps refer to the dried pandanus leaves that swirl around the nude figure's feet. In his journal Noa Noa, Gauguin compared these long leaves to "letters... of an unknown, mysterious language."

Parau na te Varua ino (Words of the Devil), 1892, oil on canvas, Gift of the W. Averell Harriman Foundation in memory of Marie N. Harriman, 1972.9.12

In Manao tupapau Western artistic traditions and Tahitian culture intermingle. The composition reflects Gauguin's deep admiration for the modernist painting Olympia (1863) by Édouard Manet. Gauguin had copied Olympia shortly before departing for Tahiti and had brought a photograph of Manet's painting with him to Polynesia. In Manao tupapau Manet's reclining nude has been transformed into a young Tahitian girl. The tupapau, or evil spirit of the dead, appears behind her in place of Manet's maidservant.

In his journal Gauguin described the inspiration for the painting: "When I opened the door... I saw [her]... she stared up at me, her eyes wide with fear, and she seemed not to know who I was.... Perhaps she took me... for one of those legendary demons or specters, the Tupapaus that filled the sleepless nights of her people."

Manao tupapau (The Spirit of the Dead Keeps Watch), 1892, oil on burlap mounted on canvas, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, A. Conger Goodyear Collection, 1965

Recreating the Past

Gauguin turned to his art to recreate the lost Tahitian culture — its gods, myths, and rituals. He claimed to have learned Tahitian mythology from his mistress, Tehamana, but it is more likely based on a 50-year-old text on Polynesia written by a Belgian ethnographer. Finding little or no trace of indigenous representations of Tahitian deities, Gauguin imagined their appearance, gathering ideas from the religious art of other ancient cultures. He was especially drawn to the goddess of the moon, Hina, whom the artist often portrayed with bent arms that echo a pose of Hindu deities, though no evidence exists that Tahitians ever showed her this way. He also depicted deities of his own invention such as the terrifying goddess Oviri.

(top left) Mahana no Atua (Day of God), 1894, oil on canvas, The Art Institute of Chicago, Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection

(top right) Merahi Metua no Tehamana (Tehamana Has Many Parents), 1893, oil on canvas, The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Deering McCormick

(bottom left) Te Rerioa (The Dream), 1897, oil on canvas, The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

(bottom right) Oviri (The Savage), 1894, stoneware, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Gauguin frequently depicted the Polynesian deity, Hina, goddess of the moon. Because he did not find any Tahitian representations of her, he looked elsewhere for inspiration, finding it in the writings of a Belgian ethnographer who had traveled to Tahiti and photographs of figures from the Javanese temple complex at Borobudur. Her haunting form, therefore, is a sort of composite deity culled from various sources and Gauguin's imagination. Rivaling the mysterious goddess is the dazzling play of color and abstract form that suggests the gently swaying waves at the shore.

Mahana no Atua (Day of God), 1894, oil on canvas, The Art Institute of Chicago, Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection

Gauguin took the young girl Tehamana as his mistress, or vahine, during his first trip to Tahiti. He described his confusion on meeting two women both claiming to be Tehamana's mother. He later learned of the Tahitian custom of having foster parents in addition to birth parents — a system that created a network of supportive relationships.

The composition blends imagery from diverse sources. The influence of Christianity in Tahiti is suggested by the modest European smock, urged on Tahitian women by missionaries; the Tahitian goddess Hina appears in the middle register, in a pose Gauguin modeled on Indian images of Hindu deities; and the undecipherable inscription along the top imitates Rongorongo writing found on Easter Island tablets, but not present in Tahiti.

Merahi Metua no Tehamana (Tehamana Has Many Parents), 1893, oil on canvas, The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Deering McCormick

When Gauguin journeyed to Tahiti for the second time, in 1895, he had a stopover in New Zealand. While awaiting his ship to be serviced, he spent time at the Auckland Museum, which held a collection of Maori art. Among the objects that he encountered there was an elaborately carved decorative bowl with two figures that formed the handles. Two years later Gauguin included a painted version of the wooden bowl in The Dream, but he converted it into a cradle for a sleeping baby. The dream of the title is uncertain. As Gauguin suggested, "Everything is dreamlike about this canvas; is it the child, is it the mother, is it the horseman on the path? Or is it the painter's dream!"

Te Rerioa (The Dream), 1897, oil on canvas, The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

Her name taken from a Tahitian word meaning "wild" or "savage," Oviri is a deity of Gauguin's imagination. Her rough, disproportionate — even grotesque — form stands in stark contrast to the ideals of Western classical beauty. Created in Paris in 1894 between stays in Tahiti, Oviri depicts a monstrous, destructive female who crushes the she-wolf at her feet, the animal's blood trickling along the base. Clutching a pup to her side, Oviri appears to have violently snatched the wolf's offspring. Gauguin considered Oviri his greatest ceramic sculpture, noting to his dealer that "no ceramist has ever produced anything like it before." He requested that it be sent back to Tahiti upon his death to be placed upon his grave; a bronze cast was eventually put there instead to better withstand the climate.

Oviri (The Savage), 1894, stoneware, Musée d'Orsay, Paris