Gilbert Stuart

Introduction

Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828) created the most lasting images of George Washington, and he also invented definitive images of the next four American presidents. This legacy alone would be enough to secure Stuart's lasting fame. However, his contribution to American portraiture extends well beyond painting the political leaders of the new republic. Stuart's subjects include prominent and lesser-known figures in both the Old and New Worlds. In addition, he introduced a new level of sophistication to the American portrait, achieving convincing likenesses and successful representations of character through his choice of pose and expression.

Like a number of early American painters, Stuart learned his trade in Great Britain. He was a sociable, loquacious fellow who delighted, exasperated, and at times offended his patrons. This complex man lived a life filled with contradictions. Although he was a prolific painter, he took years to complete some portraits and left scores unfinished, failing to deliver them at all. Despite being in demand, he often found himself in debt the was a poor manager of money who enjoyed luxury and the good life. Yet Stuart's unmatched ability to capture likeness more than compensated for his erratic behavior and earned him a devoted following. He was the most sought-after American portraitist of his era and today is counted among the greatest early American artists.

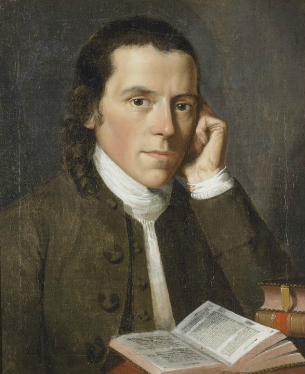

Self-Portrait, c. 1778, oil on canvas, Redwood Library and Athenaeum, Newport, Rhode Island, Bequest of Louisa Lee Waterhouse (Mrs. Benjamin Waterhouse) of Cambridge, Massachusetts

Newport and Edinburgh (1755-1775)

The son of a snuff miller, Gilbert Stuart was born in Kingston, Rhode Island, and raised in the busy harbor town of Newport. He showed an early talent for drawing, and an apprenticeship with a visiting Scottish portraitist, Cosmo Alexander, helped determine his professional path. By 1772, Stuart had accompanied Alexander to Edinburgh, where he learned to paint in the prevailing Scottish manner, a linear style that pleased Newport residents when he returned after a year abroad. Over the next few years, as he worked on local commissions, Stuart gradually began to represent individual character successfully. A portrait of his friend Benjamin Waterhouse from 1775 portends Stuart’s impending artistic transformation. This likeness, with its greater use of detail and more subtle modeling, was his most personal and finest to date.

Benjamin Waterhouse, 1775, oil on canvas, Redwood Library and Athenaeum, Newport, Rhode Island, Bequest of Louisa Lee Waterhouse

(Mrs. Benjamin Waterhouse) of Cambridge, Massachusetts

London (1775-1787)

At the outset of the American Revolution, after his loyalist family fled to Nova Scotia, Stuart moved to London. He floundered for a year on his own, earning a meager living as an organist, before being introduced to the artist Benjamin West, a fellow American who was history painter to the king, George III. West, a generous mentor to several young American artists, brought the destitute Stuart into his studio as an assistant.

With West’s guidance and under the influence of contemporary English artists such as Thomas Gainsborough and Sir Joshua Reynolds, Stuart’s technique underwent a dramatic shift. He adopted a more sophisticated use of color and modeling, employed freer brushwork, and experimented with innovative compositions, such as the portrait of William Grant skating. With its highly unusual depiction of a figure in motion, this full-length canvas received much attention. Skating, a subject frequently found in genre paintings, had been untried in portraits of this size. Soon after the exhibition of this portrait at the Royal Academy of Arts, Stuart was able to establish himself as an independent artist. He won a plum commission to paint a series of portraits of fifteen London painters and engravers and received commissions from members of the aristocracy.

The Skater (Portrait of William Grant), 1782, oil on canvas, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1950.18.1

Critics marveled at Stuart’s ability to depict the character of his sitters. One fine example is the sensitive portrait of Mohawk chief Joseph Brant, whose expression conveys a sense of both dignity and weariness. On behalf of the Iroquois nation, Brant had come to London to petition the British throne for protection of land rights, a demanding and sometimes futile role. He wears a striking costume that combines native regalia with English silver adornment, including an ornamental collar awarded by the king.

Joseph Brant, 1786, oil on canvas, The Northumberland Estates, Alnwick Castle, Collection of the Duke of Northumberland

Dublin (1787-1793)

Stuart was invited to Dublin in 1787 for a commission and seized the opportunity to escape the competition of London and his mounting debts there. Painting in the English manner of his London portraits, he quickly established himself as the most successful portraitist in Dublin; however, he took on so many commissions that he failed to finish a number of them, even after taking partial payments at the first sitting. After purchasing a farm outside the city, Stuart went into debt and landed in jail briefly in 1789. Despite this setback, his successes were numerous and included the ambitious portrait of John FitzGibbon, the newly appointed lord chancellor. Splendidly clothed in the robes of his new office, the chancellor peers out beneath a long, full wig, his haughty countenance a perfect expression of his imperious attitude. Painting this type of regal full-length portrait, meant for public display, would serve Stuart well when he returned to the United States to paint its new president.

George Washington’s defeat of the British army in the American Revolution and his inauguration as America’s first president in 1789 had made him a legendary figure in America and abroad. Stuart hatched a plan to return to America to paint Washington’s portrait and "make a fortune by Washington alone . . . if I should be fortunate I will repay my Irish and English creditors." He set sail in March 1793, leaving numerous unfinished canvases behind, remarking, "The artists of Dublin will get employed in finishing them."

John FitzGibbon, c. 1789–1790, oil on canvas, The Cleveland Museum of Art, General Income Fund

New York (1793-1794)

Rather than heading directly to Philadelphia, the nation’s capital from 1790 to 1800, Stuart went first to New York, a smaller cosmopolitan city nearly devoid of fine portraitists. Stuart had few contacts in New York, but they proved significant enough to initiate demand for his work. Chief Justice John Jay, whose earlier portraits he had left unfinished in London, sat again and introduced him to prospective patrons. Other clients included Spanish envoy Josef de Jaudenes y Nebot and his sixteen-year-old American bride Matilda Stoughton, whose portraits Stuart painted about the time of their marriage. Señora de Jaudenes is elaborately dressed in a billowing gown decorated with jewels and a headdress of ostrich feathers, a costume that suggests the height of her husband’s political and social ambitions.

John Jay, 1794, oil on canvas, Gift (Partial and Promised) of the Jay Family, 2009.132.1

Stuart noted, "In England my efforts were compared with those of Van Dyck, Titian, and other great painters––but here! They compare them with the works of the Almighty!" At times his American clientele allowed him an even greater candor in portrayal than was encouraged in Great Britain. For example, the formidable Catherine Brass Yates, wife of New York merchant Richard Yates, epitomizes restraint and propriety. Every detail in this brilliant painting is instrumental to the entire effect, from the silvery sheen of Mrs. Yates’ neatly fitted attire to the precision of her nimble fingers pulling at the taut line of thread. Stuart mixed these particulars with an unvarnished study of facial features, rendering the slightly crooked line of Mrs. Yates’ prominent nose, her primly closed mouth, the thick, arched line of her eyebrow, and her cool, unrelenting gaze. The result is one of his most compelling and unified efforts at conveying character.

Catherine Brass Yates (Mrs. Richard Yates), 1793/1794, oil on canvas, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1940.1.4

Philadelphia (1794-1803)

In 1794, with a letter of introduction from John Jay in hand, Stuart went to Philadelphia to request sittings with George Washington. Painting his portrait was a shrewd business move, for depictions of Washington were in demand on both sides of the Atlantic. Stuart’s established technique for finding appropriate expressions and poses for his sitters was to engage them with lively banter. When he encountered Washington, however, he found the president to be a difficult sitter. Stuart’s usual charm and repartee failed to enliven this reserved man. According to Washington’s grandson George Washington Parke Custis, Stuart finally succeeded in engaging him by discussing horses, a favorite topic of the president, who was an accomplished equestrian.

Each of Stuart’s portraits of Washington (about one hundred in all) is based on one of three life portraits. Washington first sat for Stuart in 1795, but the result of that early session, a portrait showing Washington facing right, is known only through replicas that are identified as the Vaughan type (named for the first owner of one of the replicas). That first portrait was so successful that Martha Washington commissioned Stuart to paint a pair of portraits of her and her husband for their Virginia home, Mount Vernon. Stuart began what would become his most reproduced image, a depiction of Washington facing left, now called the Athenaeum portrait for the Boston library that acquired it after Stuart’s death. Although he never finished the original itself, he used it throughout his career to make approximately seventy-five replicas, and the image––carefully built up with contrasting flesh tones––is one of Stuart’s most accomplished portraits. Creating it was not an easy task; when the president came to sit for the portrait, his newly acquired set of false teeth created a bulge around the mouth and distorted his jawline.

George Washington (The Athenaeum Portrait), 1796, oil on canvas, Jointly owned by the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, William Francis Warden Fund, John H. and Ernestine A. Payne Fund, Commonwealth Cultural Preservation Trust

In 1796 the president sat a third time. This full-length canvas envisions Washington in the role of civilian leader, in a formal black velvet suit rather than his military uniform. The portrait is known as the Lansdowne because it was commissioned as a gift for the Marquis of Lansdowne. The composition, which reflects Stuart’s knowledge of European state portraiture, includes objects symbolic of Washington’s illustrious military and civil leadership, while his oratorical pose, with hand extended, refers, according to contemp- oraries, to his recent speech to Congress. The image was celebrated in America and England upon its completion, and Stuart was commissioned to paint several replicas.

George Washington (The Lansdowne Portrait), 1796, oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, Acquired as a gift to the nation through the generosity of the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation

Washington, D.C. (1803-1805)

Stuart stayed in Philadelphia for about nine years, occupied with painting the first president as well as with commissions from Washington’s many admirers for their own portraits. After a quick visit to Washington, DC, in 1802, however, he decided to relocate his studio in the new federal capital. Stuart’s friend, architect Benjamin Latrobe, designed and constructed a two-room building for him north of Pennsylvania Avenue (near Sixth and C Streets, not far from the present site of the National Gallery of Art). In Washington he was "all the rage," in the words of one contemporary. Dozens of sitters––including President Thomas Jefferson, congressmen, foreign diplomats, businessmen, and landowners––were eager to have their likenesses captured and anxious to have them completed before Stuart tired from the demand.

As was the case in Philadelphia, most of his Washington, DC, portraits are small, waist-length canvases. This format allowed him to finish the works quickly while depicting a variety of individual poses and gestures. One of his more unusual portraits is the small, 1805 medallion profile of Thomas Jefferson, done at the request of the president. This monochromatic wash drawing, whose format emulates Roman coin portraiture, depicts Jefferson with the fashionably short haircut that was to replace the older style worn by earlier patriots (including Washington). Those who knew Jefferson considered it to be one of the best likenesses ever taken of him.

Stuart suffered from malaria in the summer of 1804 and again in the spring of 1805, and the illness affected his work. Latrobe pleaded with him, "Let me... intreat you to leave that sink of your health, your Genius, and your interests, Washington... God bless You and give you resolution to start off to a climate more healthy and less tainted with fraud, speculation, marsh miasmata, and the insolence of clerkships." A short time later, Latrobe, who was also Stuart’s landlord, was granted his wish, but perhaps with regret: Stuart skipped out on some of the rent he owed.

Thomas Jefferson (The Medallion Portrait), 1805, grisaille of aqueous medium on paper on canvas, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Gift of Mrs. T. Jefferson Newbold and family, in memory of Thomas Jefferson Newbold, Class of 1910

Boston (1805-1828)

Stuart left Washington for Boston at the invitation of Massachusetts senator Jonathan Mason, who promised to introduce him to friends, relatives, and associates there. He found patronage among a range of the city’s residents, including Paul Revere and mayor Josiah Quincy as well as younger sitters like Lydia Smith, whose complex portrait reveals her to be an accomplished young lady with both musical and artistic talents. At first Stuart may have considered Boston a temporary stop––he reported to a friend that the city was too cold for him––but he spent his last twenty-three years there, in demand not only as a portraitist but also as a guest at dinners and other social events. He was visited by many younger artists who sought advice or simply wished to pay their respects.

Lydia Smith, c. 1808–1810, oil on wood, Private collection

Stuart's strengths as an artist did not diminish as he grew older, even though his tremulous hand occasionally handled paint in a less exacting way. His late, life portrait of John Adams is a moving image of the frailty and dignity of old age. The ninety-year-old former president clasps his cane with bony fingers rendered in strong highlights and thin areas of shadow. Although his body is aged, Adams' alertness shines through in his blue eyes, which return the viewer’s gaze clearly and directly. The portrait is a tribute both to the elder statesman’s enduring personality and to Stuart's unflagging abilities in his own final years.

John Adams, 1823–1824, oil on canvas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Bequest of Charles Francis Adams