Gordon Parks Photography

The youngest of 15 children, Gordon Parks was born in 1912 (d. 2006) in Fort Scott, Kansas. His parents had moved there from Tennessee in the years following the post–Civil War Reconstruction period. Although he was close with his supportive family, Parks could not ignore the inequality and racism around him. He recalls, “The indignities came so often that I soon began to accept them as normal. But I always fought back.”

Parks purchased his first camera in 1937 and committed himself to becoming a photographer. A consummate observer of the world, he found inspiration in magazines, museums, and books. He began experimenting with portraiture and some of his photographs were featured in the local African American newspaper in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Though primarily self-taught, Parks’s education was influenced by other artists and mentors he encountered in the early part of his career. He would go on to achieve extraordinary success in his field, a major accomplishment for an African American photographer during the 1940s. In addition to photographing for Life, Ebony, and Vogue, Parks was a poet, author, musician, and filmmaker.

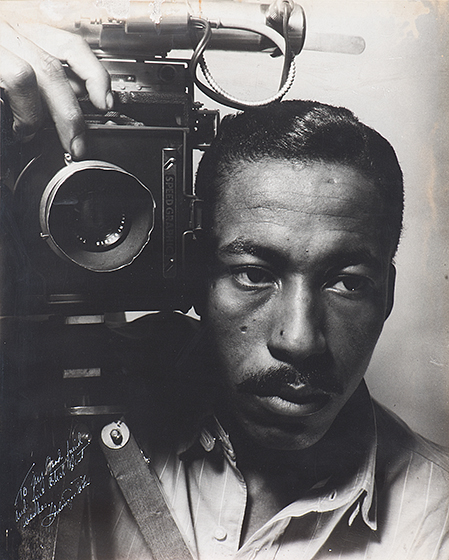

Parks was just 28 years old when he took this self-portrait. He carefully composed it to demonstrate his close connection with his vocation: his face is aligned with the lens of his camera (one typical of those used by press photographers at the time) and his expression is quite contemplative.

Gordon Parks, Self-Portrait, 1941, gelatin silver print, 50.8 × 40.64 cm (20 × 16 in.), Private Collection. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Early in his career, Parks found success as a fashion and portrait photographer. Marva Trotter Louis, socialite, fashion designer, and wife of famous heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis, was an early supporter of Parks. She was one of many people who encouraged him to move to Chicago in the early 1940s.

Here, Parks demonstrates the power of fashion, pose, gaze, and lighting as tools to both convey the personality of the subject as well as make a captivating image. What do you notice first about Marva Trotter Louis? Observe her clothing: floral dress, long gloves, hat, and veil. Look at her pose: relaxed, turned body; hand on hip; and a gaze which directly meets our own eyes. What do these elements say about her? Dramatic lighting casts only one side of her body in light; a dark shadow in profile dominates the left side of the image. Why might Parks have arranged his composition this way?

Discuss how this image either challenges or reinforces your notions about race, gender, class, and power. How might this portrait have been perceived in 1941, the year it was taken?

Gordon Parks, Marva Trotter Louis, Chicago, Illinois, 1941, gelatin silver print, image: 24.13 × 20 cm (9 1/2 × 7 7/8 in.), sheet: 25.4 × 20.64 cm (10 × 8 1/8 in.), The Gordon Parks Foundation, GP04581. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

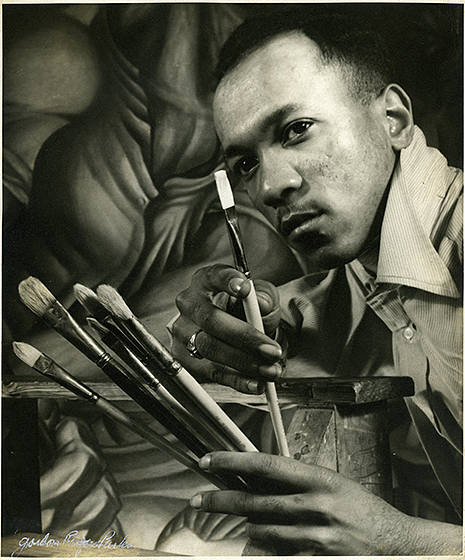

Parks moved to Chicago in 1941 and became affiliated with the South Side Community Art Center, where he had a studio and darkroom. He developed relationships with a number of artists living and working in Chicago, including Charles White. White encouraged Parks, who was primarily shooting portraits, to take his camera into the streets and document the poverty he found there.

With his own tools in hand, White is featured in front of his mural, Chaos of the American Negro. What strategies does Parks use in his composition to communicate his respect for this artist? Compare this portrait with Parks’s Self-Portrait also taken in 1941 (Slide 1). What similarities and differences do you notice?

Learn more about Charles White

Gordon Parks, Charles White in front of his mural “Chaos of the American Negro,” 1941, gelatin silver print, image: 24 × 19.8 cm (9 1/2 × 7 13/16 in.), framed: 25.3 × 20.2 cm (9 15/16 × 7 15/16 in.), Charles White Archives. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

As a leader of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes addressed important racial issues of the day through his poetry, essays, and plays. His work inspired many African American artists, including Gordon Parks. Parks had moved to Chicago in 1941, and through his work with the South Side Community Art Center had further developed the psychological content of his portraits.

The frame-within-a-frame composition of this portrait strikes a playful note, counterbalanced by Hughes’s sober, contemplative expression. Is this a portrait of Hughes or his hand? Physically separated from the rest of his body by the frame, his hand and arm take on a special prominence in the photograph, suggesting Hughes’s power as a writer.

Parks took this photograph just a couple of weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which brought the United States into World War II.

Gordon Parks, Langston Hughes, Chicago, December 1941, gelatin silver print, printed later, Corcoran Collection (The Gordon Parks Collection), 2016.117.102

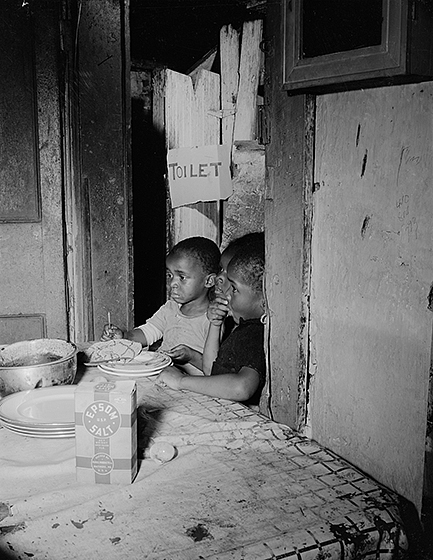

This is one of many photographs that Parks made in Washington while working for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), a government agency. Roy Stryker, the head of the FSA’s Historical Section, encouraged Parks to look closely at photographs by other agency photographers before beginning his own work. The subject and carefully arranged composition of this photograph demonstrate the influence of that research. Parks uses strong lighting to illuminate a dark, dirty interior with three young children sitting underneath a handwritten sign indicating the bathroom behind them. In the foreground is a box of Epsom salt, perhaps a nod to the daily manual labor performed by the unseen adults in the house. The photograph is documentary in nature, but also highly manipulated and evocative.

Parks included captions with his photographs meant to provide background information. The caption states that the three subjects are waiting for their mother to prepare dinner. How does this additional information help you read the image?

If you could give this photograph a title (instead of a caption), what would it be?

Gordon Parks, Washington, D.C. Three children waiting in the kitchen while their mother prepares the evening meal. June 1942, gelatin silver print, sheet: 23.7 × 18.7 cm (9 5/16 × 7 3/8 in.), mount: 29 × 24 cm (11 7/16 × 9 7/16 in.), Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

In 1941 and 1942, under the auspices of the Federal Public Housing Authority and the Alley Dwelling Authority (later renamed the National Capital Housing Authority), new public housing, such as the Frederick Douglass Dwellings in the Anacostia neighborhood of Washington, DC, was erected for black defense workers. At this time housing, theaters, restaurants, and many shops in the nation’s capital were segregated. Parks was assigned to cover life in the housing project.

What can we learn about this family from looking at this photograph? Why might the government have assigned a photographer to document life at this housing project?

Consider that this picture was taken just months after the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, when the American government was actively preparing for war. Black Americans sought ways to support the war effort by enlisting in the military or working in defense industries, but often faced discrimination in their attempts to do so. Government-produced images such as this one offered hope for the future by demonstrating that life was getting better for African Americans, an idealistic representation of the lived experience at the time.

Gordon Parks, Anacostia, D.C. Frederick Douglass Housing Project. A family says grace before the evening meal. June 1942, gelatin silver print, image: 19.3 × 24 cm (7 5/8 × 9 7/16 in.), sheet: 20.6 × 25.2 cm (8 1/8 × 9 15/16 in.), The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by Mrs. Clare A. Glassell

In the foreground of this photograph, two young boys are engaged in play. The caption indicates that the run-down structure in the alley behind them, surrounded by trash and urban squalor, is their home. The boys, so immersed in their game, seem unaware of their surroundings as well as the photographer capturing this moment.

What does this photograph tell you about the living conditions in Washington, DC, in 1942? What details in the photograph support your conclusions? Imagine you are a government official seeing this photograph for the first time. Does it inspire you to take action? Why or why not? Support your thinking with details from the photograph.

Gordon Parks, Washington (southwest section), D.C. Two Negro boys shooting marbles in front of their home. November 1942, gelatin silver print, image: 9.2 × 11.7 cm (3 5/8 × 4 5/8 in.), sheet: 10 × 12.4 cm (3 15/16 × 4 7/8 in.), The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Mundy Companies. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

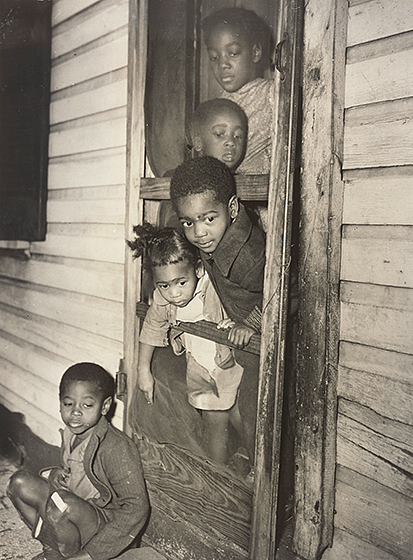

What has brought these five children to the front door of their home? Why has Parks chosen to photograph them in particular?

Parks gives us little visual information to answer those questions. Instead, he offers us a moment to contemplate each of these children individually. What must their lives be like? What do their expressions and crowded arrangement by the door tell us about their connections as family? Parks had a particular sensitivity to capturing the spirit, hope, and humanity of young people in urban and rural settings.

Gordon Parks, Washington (southwest section), D.C. Negro children in the front door of their home. November 1942, gelatin silver print, 33.66 × 24.77 cm (13 1/4 × 9 3/4 in.), Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

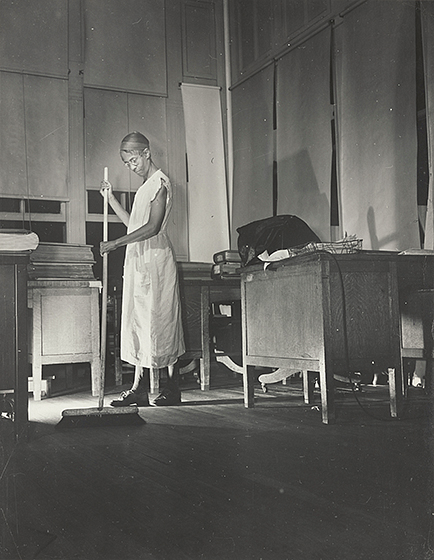

As one of Parks’s first assignments for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), he interviewed Ella Watson, who was cleaning offices at the Department of Agriculture, where the FSA was housed. He learned of her story of hardship and with her permission photographed her not only at work, but at home, with her family, and in her community. It was from this series of approximately 85 images that Parks produced one his most iconic works, Washington, D.C. Government charwoman (American Gothic). The additional photographs in the series offer a multilayered presentation of Ella Watson’s life. Many of the images reflect the oppression and hardship she, like Parks, experienced in Washington, DC, but they also show moments of spirituality, love, and hope.

In this photograph, Parks shows Ella Watson alone, cleaning one of the many government offices. The harsh light focused on one point on the floor casts Watson into the shadows of the room, hinting at the invisibility of her work. Consider the role of light in this photograph and compare it to Parks’s portrait of Marva Trotter Louis.

What can we learn about Ella Watson’s professional and personal life from this photograph?

Learn more about Washington, D.C. Government charwoman (American Gothic)

Gordon Parks, Washington, D.C. Government charwoman cleaning after regular working hours. July 1942, gelatin silver print, 35.56 × 27.94 cm (14 × 11 in.), Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

As one of Parks’s first assignments for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), he interviewed Ella Watson, who was cleaning offices at the Department of Agriculture, where the FSA was housed. He learned of her story of hardship and with her permission photographed her not only at work, but at home, with her family, and in her community. It was from this series of approximately 85 images that Parks produced one his most iconic works, Washington, D.C. Government charwoman (American Gothic). The additional photographs in the series offer a multilayered presentation of Ella Watson’s life. Many of the images reflect the oppression and hardship she, like Parks, experienced in Washington, DC, but they also show moments of spirituality, love, and hope.

This is an image of Watson at home with her family. We glimpse her adopted daughter, Loretta, in the reflection of the mirror (on the right), seemingly contemplating the photograph of Watson’s parents, also visible to us. Watson is surrounded by her grandchildren in the kitchen, perhaps enjoying some time together after dinner. Four generations are included in this photograph, demonstrating the importance of Watson’s extended family.

What can we learn about Ella Watson’s professional and personal life from this photograph?

Learn more about Washington, D.C. Government charwoman (American Gothic)

Gordon Parks, Washington, D.C. Mrs. Ella Watson, a government charwoman, with three grandchildren and her adopted daugther, July 1942, gelatin silver print, printed later, Corcoran Collection (The Gordon Parks Collection), 2016.117.106

Compare this photograph with the one of Ella Watson similarly sitting by an open window, both taken by Parks in 1942 in Washington, DC. What details do you notice that help to tell each woman’s story? Why do you think he has us looking at the backs of their heads? Do you consider these works to be portraits? Why or why not?

What is Parks possibly communicating about race and gender in 1940s America?

Gordon Parks, Anacostia, D.C. Frederick Douglass housing project. Mother watching her children as she prepares the evening meal. June 1942, gelatin silver print, 25.4 × 20.3 cm (10 × 8 in.), Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Compare this photograph with the one of a mother in the Frederick Douglass housing project similarly sitting by an open window, both taken by Parks in 1942 in Washington, DC. What details do you notice that help to tell each woman’s story? Why do you think he has us looking at the backs of their heads? Do you consider these works to be portraits? Why or why not?

What is Parks possibly communicating about race and gender in 1940s America?

Gordon Parks, Washington, D.C., Mrs. Ella Watson, a Government Charwoman, July 1942, gelatin silver print, printed 1960s, Gift of Julia J. Norrell, 2015.119.1

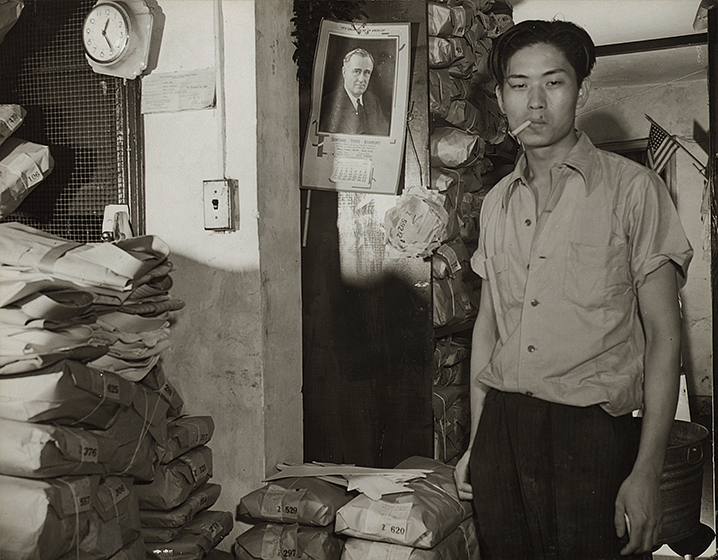

As the caption indicates, Parks took this photograph as part of his work documenting Ella Watson’s life. This photograph offers a glimpse of the diversity of people who contributed to life and labor in and around Washington, DC. It is impossible to ignore that the subject, Johnnie Lew, is flanked by a picture of 32nd President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (over his right shoulder) and an American flag (which waves above his left shoulder).

How does this image contribute to the story of labor in the United States?

Gordon Parks, Washington, D.C. Johnnie Lew, owner of the laundry under the apartment of Mrs. Ella Watson, a government charwoman, August 1942, gelatin silver print, sheet: 18.2 × 23.3 cm (7 3/16 × 9 3/16 in.), mount: 24.1 × 29 cm (9 1/2 × 11 7/16 in.), Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

In 1943, the increasingly unpopular Farm Security Administration (FSA) was abolished, pieces of which were then absorbed into the Office of War Information (OWI). Before the FSA closed though, Parks was selected to transfer to the OWI, which he did in October 1942. He was assigned as a war correspondent to cover the 332nd Fighter Group, the first regiment of black pilots, who were training near Detroit, Michigan. Parks’s attempts to travel with the pilots for their first deployment abroad were continually thwarted by officials in the federal government, some of whom were not supportive of black pilots receiving such publicity.

Gordon Parks, Lt. George Knox. 332nd Fighter Group training at Selfridge Field, Michigan, October 1943, gelatin silver print mounted on board with caption, image: 25.4 × 26.35 cm (10 × 10 3/8 in.), sheet: 27.31 × 26.35 cm (10 3/4 × 10 3/8 in.), The Gordon Parks Foundation, GP02596. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks took this photograph while on assignment for the Standard Oil Company (New Jersey), a corporation suffering a massive public relations crisis related to a rubber shortage that threatened the country’s ability to fight in World War II. Part of Parks’s assignment was to represent how the oil industry positively impacted life in the United States. Parks spent eight days with the Brown family, pictured here sharing a family meal.

Look closely at who is gathered around the table. Hercules Brown sits with his wife, three daughters, and grandson. His son-in-law is away fighting in the war. What can you learn about this family based on what you see in the photograph? Notice how we, as the viewer, seem to be looking down at the table. Where do you think Parks was when he took this picture?

Compare with this image with Anacostia, D.C. Frederick Douglass Housing Project.

Gordon Parks, Dinner Time at Mr. Hercules Brown's Home, Somerville, Maine, February 1944, gelatin silver print, printed later, Corcoran Collection (The Gordon Parks Collection), 2016.117.128

Employed by Penola, Inc., this anonymous African American worker toils to clean grease barrels by dipping them in boiling lye. The only human presence in a landscape of steam and steel, Parks uses dramatic lighting and a low angle to present him as a hero of industry. Understanding that his efforts were one part of an intricate system to supply essential lubricants to the military fighting overseas elevates him to the status of American hero, perhaps.

Parks wrote to Roy Stryker from Pittsburgh: “Photographing the grease plant at Pittsburgh was a pretty nasty job. It was nasty because in every building and on every floor grease was underfoot. The interiors in the older buildings were extremely dark and absorbed plenty of light, so it was necessary to use long extensions and many bulbs. The extensions throughout the day were covered with grease….I might add that a day at the grease plant leaves one with an enormous appetite.”

Is this an image of American progress? Why or why not?

Gordon Parks, Pittsburgh, Pa. The cooper’s plant at the Penola, Inc. grease plant, where large drums and containers are reconditioned. March 1944, gelatin silver print, sheet: 23.9 × 19.1 cm (9 7/16 × 7 1/2 in.), mount: 29 × 24 cm (11 7/16 × 9 7/16 in.), Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

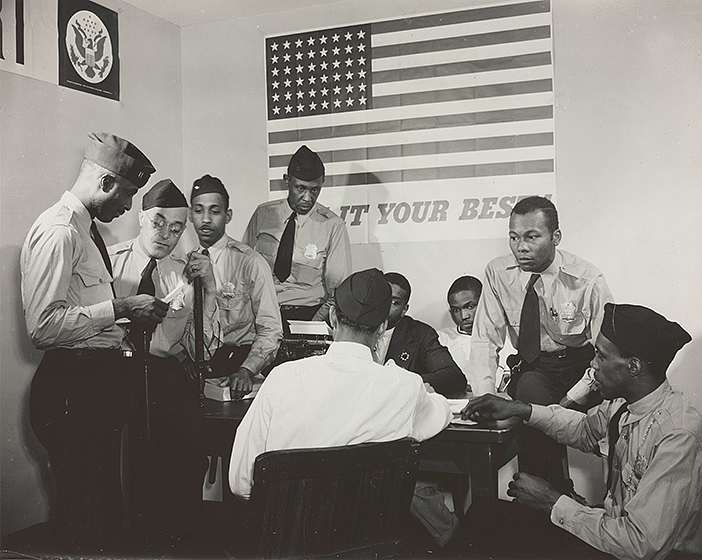

In 1942, Washington, DC, was still a segregated city. This meant that civilian defense activities, such as this group of auxiliary police (reserves who could be called up in an emergency), were also segregated. Serious, uniformed men gather around their instructor against the backdrop of a large American flag and the motto “GIVE IT YOUR BEST.” We have every reason to believe they are doing just that.

This posed photograph made a case for the kind of patriotism that included efforts by all Americans, regardless of race, to help the country fight and win World War II.

Gordon Parks, Washington, D.C. Auxiliary police at a weekly meeting, July 1942, gelatin silver print, 20.32 × 25.4 cm (8 × 10 in.), Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Given its reliance on oil and lubricants, transportation was an important theme for the documentary photographers at Standard Oil Company (New Jersey). New York Harbor, where crowds of commuters made their way to Manhattan on the Staten Island Ferry, represented the epicenter of this idea.

Consider the perspective in this photograph: Where is the photographer standing to take this picture? What does this photograph tell us about the nature of work in the United States? Who is present? Who is missing?

Gordon Parks, Ferry boat from Staten Island to Manhattan, carrying early morning commuters, New York City, November 1946, gelatin silver print, printed later, Corcoran Collection (The Gordon Parks Collection), 2016.117.129

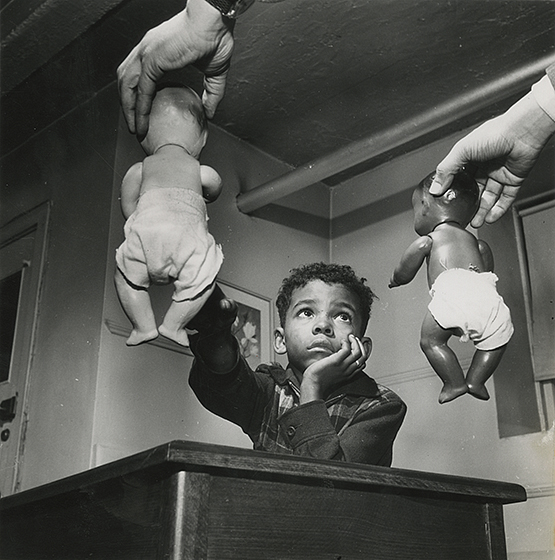

Here, Parks tackles issues of race in a visibly bold manner, reminiscent of his work Washington, D.C. Government charwoman (American Gothic).

Parks took this picture on assignment for Ebony magazine in 1947 for an article called, “Problem Kids: New Harlem clinic rescues ghetto youth from emotional short circuit.” The article featured the work of psychiatrists Mamie and Kenneth Clark, whose “doll test” research investigated issues of segregation and self-esteem in black children. African American children in segregated schools were shown a black doll and a white doll and then asked to choose one. The majority picked the white doll, indicating that segregation impacted the children’s feelings of self-worth. Their research, while not wholly scientific, was used in school desegregation lawsuits including Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Imagine you are the editor of Ebony magazine. Would you have chosen to include this image in your story? Why or why not?

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Harlem, New York, 1947, gelatin silver print, image: 17.78 × 17.46 cm (7 × 6 7/8 in.), sheet: 20.32 × 18.42 cm (8 × 7 1/4 in.), The Gordon Parks Foundation, GP04135. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

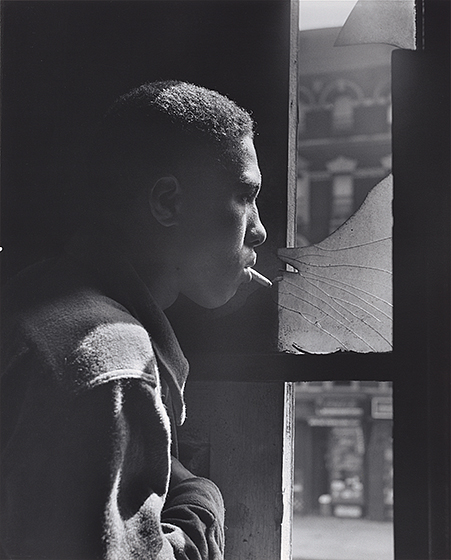

On assignment for Life magazine, Parks followed Leonard “Red” Jackson, a 17-year-old Harlem gang leader. Parks’s photo essay captured the violence and fear experienced by gang members and their families, and positioned him as an important documentary photographer. A year later, Parks would become the first African American to be named staff photographer at Life. Forty years later, Parks ran into Red Jackson, who suggested, “You know, you and me could go back up to Harlem together and save some of those kids up there. I’m always asking myself about how I got into so much trouble” (Gordon Parks, Half Past Autumn: A Retrospective [Boston, 1999], 84).

This photograph does not directly depict the danger associated with gang violence. Jackson does not face the camera, yet the photograph offers close, almost intimate, access to the subject. It invites us to consider what he might be thinking, seeing, or feeling. What role might these photographs play in a larger essay on gang violence? Do they offer hope? Describe how the setting, details, and lighting in each photograph inform your opinion.

Gordon Parks, Trapped in abandoned building by a rival gang on street, Red Jackson ponders his next move, 1948, gelatin silver print, Corcoran Collection (The Gordon Parks Collection), 2015.19.4605

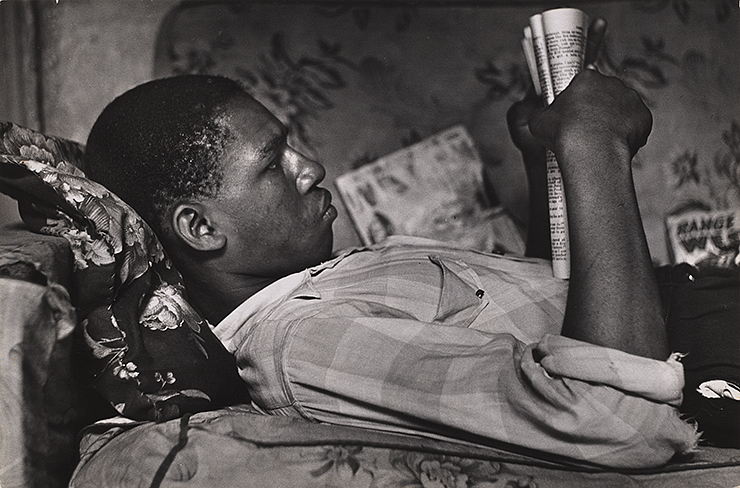

On assignment for Life magazine, Parks followed Leonard “Red” Jackson, a 17-year-old Harlem gang leader. Parks’s photo essay captured the violence and fear experienced by gang members and their families, and positioned him as an important documentary photographer. A year later, Parks would become the first African American to be named staff photographer at Life. Forty years later, Parks ran into Red Jackson, who suggested, “You know, you and me could go back up to Harlem together and save some of those kids up there. I’m always asking myself about how I got into so much trouble” (Gordon Parks, Half Past Autumn: A Retrospective [Boston, 1999], 84).

This photograph does not directly depict the danger associated with gang violence. Red Jackson's brother does not face the camera, yet the photograph offers close, almost intimate, access to the subject. It invites us to consider what he might be thinking, seeing, or feeling. What role might these photographs play in a larger essay on gang violence? Do they offer hope? Describe how the setting, details, and lighting in each photograph inform your opinion.

Gordon Parks, Red’s Younger Brother at Home, Harlem, 1948, gelatin silver print, image: 22.1 × 33.4 cm (8 11/16 × 13 1/8 in.), framed: 40.64 × 50.8 cm (16 × 20 in.), The Cleveland Museum of Art, Norman O. Stone and Ella A. Stone Memorial Fund, 2002.70

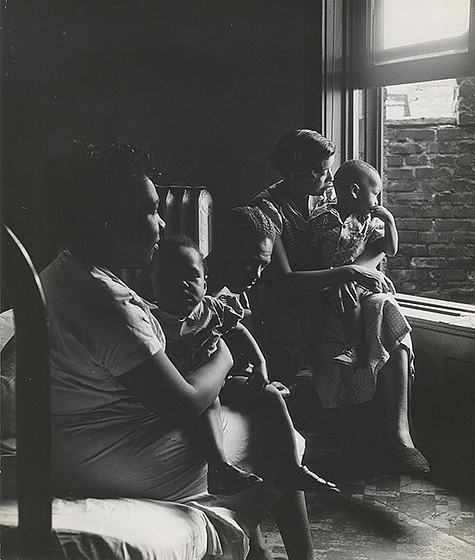

In 1950, Life assigned Parks to produce a story about school segregation, then an increasingly important issue in the nation’s discourse on civil rights. Parks chose to return to his hometown of Fort Scott, Kansas, to find out what had become of his classmates from the segregated Plaza School. Part documentary, part nostalgia, this trip offered Parks a chance to reflect on how his understanding of a place changed with time and how segregation affected the lives of his classmates and friends.

Compare the two photographs of Parks’s former classmates. They ended up in different cities, Chicago and Detroit respectively. What else is different about their life paths? How might they each represent the effects of segregation?

Imagine you had the opportunity to return to your hometown 30 years from now. What might you expect to see? What would you photograph?

Gordon Parks, Tenement Dwellers, Chicago, 1950, gelatin silver print, 32.7 × 27.62 cm (12 7/8 × 10 7/8 in.), The Gordon Parks Foundation, GP04541. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

In 1950, Life assigned Parks to produce a story about school segregation, then an increasingly important issue in the nation’s discourse on civil rights. Parks chose to return to his hometown of Fort Scott, Kansas, to find out what had become of his classmates from the segregated Plaza School. Part documentary, part nostalgia, this trip offered Parks a chance to reflect on how his understanding of a place changed with time and how segregation affected the lives of his classmates and friends.

Compare the two photographs of Parks’s former classmates. They ended up in different cities, Chicago and Detroit respectively. What else is different about their life paths? How might they each represent the effects of segregation?

Imagine you had the opportunity to return to your hometown 30 years from now. What might you expect to see? What would you photograph?

Gordon Parks, Husband and Wife on Sunday Morning, Detroit, Michigan, 1950, gelatin silver print, 40.01 × 49.85 cm (15 3/4 × 19 5/8 in.), The Gordon Parks Foundation, GP06161. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation