Harlem Renaissance

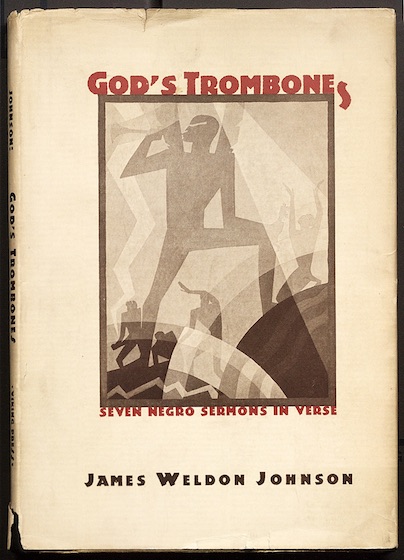

Two artists collaborated on this famous Harlem Renaissance–era book, which combines interpretations of biblical parables written in contemporary verse with bold illustrations that echo the power and symbolism of the words.

The writer James Weldon Johnson, author, poet, essayist, and chronicler of Black Manhattan (the title of one of his books), commissioned Aaron Douglas to illustrate God’s Trombones. The book is organized into eight chapters: an explanatory preface by Johnson and introductory prayer followed by seven sermon-poems entitled “The Creation,” “The Prodigal Son,” “Go Down Death—A Funeral Sermon,” “Noah Built the Ark,” “The Crucifixion,” “Let My People Go,” and “The Judgment Day.” Each sermon adopts the vernacular of an African American preacher and is accompanied by dynamic, black-and-white illustrations that cast the stories in a contemporary light and feature black protagonists. Douglas’s painting style used bold coloration, but printing processes of the 1920s made color illustrations difficult and costly, which is why the illustrations are monochrome with text offset in a single color.

Learn more about this work here

James Weldon Johnson, God's Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse, 1927

Years after the 1927 publication of God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse, Aaron Douglas painted new works of art based on his original illustrations for the book. The artist’s use of complementary colors (purple and yellow/green) combined with overlapping arcs, zigzagging shapes, and the silhouetted figures’ extended limbs create an energized composition. The central figure, who is outsize to show his importance (a device used in ancient Egyptian art, which was an influence on Douglas’s style) represents Gabriel, an archangel appearing in the Old and New Testaments of the Bible who serves as God’s messenger and whose name means “God is my strength.” The other figures respond to Gabriel’s call and the pulsating forms suggest the trumpet’s echoing sound. The verse that accompanied the illustration published in God’s Trombones likens Gabriel to a blues trumpeter:

And Gabriel’s going to ask him: Lord,

How long must I blow it?

And God’s a-going to tell him: Gabriel,

Blow it calm and easy.

Then putting one foot on the mountain top,

And the other in the middle of the sea,

Gabriel’s going to stand and blow his horn.

To wake the living nations.

Aaron Douglas, The Judgment Day, 1939, oil on tempered hardboard, Patrons' Permanent Fund, The Avalon Fund, 2014.135.1

This painting refers to the Atlantic slave trade, during which 10–12 million people were trafficked from Africa to the Americas, most during the period from the 1600s to the 1800s. The United States outlawed further slave trade into the country in 1808, although the practice itself was not abolished until 1864. The painting positions us as viewers behind a scrim of foliage, as if we are hiding or witnessing the scene. There is a receding line of male figures, heads bowed, advancing toward the ocean and approaching ships that will forcibly transport them to a foreign place and life of enslavement. Aaron Douglas uses nonnaturalistic, complementary colors—teal-blue figures and a searing, lemon-yellow sky—to add drama. Wrist shackles are painted a contrasting orange, which draws our eye to them. One figure has dropped to his knees in the foreground, arms raised beseechingly heavenward, while a central standing figure gazes at a single star whose beam of light illuminates him, perhaps a reminder that he is not forsaken.

Aaron Douglas, Into Bondage, 1936, oil on canvas, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase and partial gift from Thurlow Evans Tibbs, Jr., The Evans-Tibbs Collection), 2014.79.17

Fritz Winold Reiss and his family emigrated from Germany to the United States in 1913. He traveled extensively around the United States and Mexico, and became interested in America’s racial diversity, frequently portraying indigenous Americans and African Americans. Reiss illustrated The New Negro, Alain Locke’s influential anthology of writing, thought, and verse that became an emblem of the Harlem Renaissance. Published in 1925, The New Negro asserted the unique qualities of black American culture and life and encouraged ownership and pride in its art and heritage.

Reiss, who was white, was inspired by the same sources as black artists and designers: modern European art and the stylized forms of African art, including ancient Egyptian art (see the related Pinterest board for examples). Here, the figures, shown only in profile, are compressed into a geometrical space throbbing with active lines and movement. One figure appears to tend the hair of another, while the multiply breasted figure could be a goddess or symbol of fertility. Reiss’s active composition of jagged lines and radiating forms influenced Aaron Douglas.

Fritz Winold Reiss, Untitled (Two Figures in an Incline), woodcut, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.4080

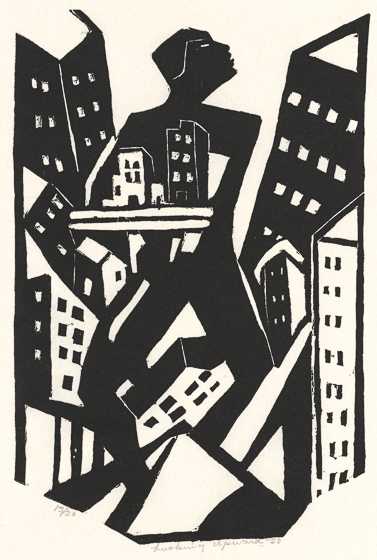

James Lesesne Wells found inspiration in the stylized qualities of African sculpture and in German expressionist art, which revived the centuries-old medium of woodcut printing for the modern age. This work shows an outsize, silhouetted figure making his way among, and dominating, an urban forest of skyscrapers that seem to tumble in his wake. He appears to carry a small model of other dwellings, perhaps a representation of home or the idea of home we retain in memory. The figure looks about him, as if seeking or aspiring to fit in or establish roots. Many African Americans elected to move from the South to Northern cities during the Great Migration, experiencing both displacement and adjustment to new urban environments.

James Lesesne Wells, Looking Upward, 1928, woodcut in black on laid paper, Ruth and Jacob Kainen Collection, 1994.87.9

Richmond Barthé sculpted African American subjects in a sensitive, realist style. Barthé followed a classical style in sculpture, believing that any subject could be dignified and beautiful if rendered with skill and thoughtfulness. Up until the Harlem Renaissance, African American faces rarely appeared as the central subject of visual art. Barthé’s art and interest in the male figure was informed by his identity as a gay man, who according to the times was constrained in disclosing this part of his life openly, although he did find fellowship and love interests among the period’s artists and intellectuals.

Barthé grew up in New Orleans and headed north with the support of his family to pursue an artistic education at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), where he studied painting. At the time, SAIC and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts were the two US art schools that admitted African American students. Barthé discovered his talent for sculpture in 1927, when he was introduced to the medium during a class assignment to create a portrait bust of a fellow student in clay (he completed two). These initial works were noticed by the instructor and included in an exhibition, The Negro in Art Week, launching Barthé’s career and lifelong commitment to sculpture.

Richmond Barthé, Head of a Boy, c. 1930, painted plaster, Corcoran Collection (The Evans-Tibbs Collection, Gift of Thurlow Evans Tibbs, Jr.), 2014.136.295

In 1930, Werner Drewes emigrated to New York City from Germany, where he had been an art student. This work is from the same year he arrived in New York and pays homage to African American womanhood and beauty. The image, created by a white artist who worked in circles outside of Harlem, attests to the widespread cultural impact of the Harlem Renaissance, of interest to people across racial and social lines, including artists, teachers, patrons, and funders who engaged in pluralist, interracial dialogues. Drewes occasionally made images of people and scenes in Harlem and other New York locations. Harlem Beauty has a timeless and sculptural quality, with its stripped-down focus on the woman’s illuminated face in profile, a classical portrait style. Drewes, like Fritz Winold Reiss, was associated with a modernist European tradition that likewise was of interest to many African American artists during the Harlem Renaissance. Can you think of other examples of cultural dialogue, wherein seemingly distinct populations influence each other’s artistic practices?

Drewes worked in President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) artist employment programs as an art teacher at the Brooklyn Museum and Columbia University. He later headed the graphic arts division of the Federal Art Project, part of the WPA, in New York state. He was a prolific printmaker and, later, painter.

Werner Drewes, Harlem Beauty, 1930, woodcut in black, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1974.84.1

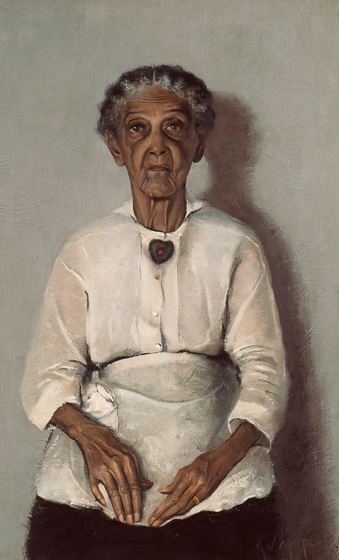

The extended Motley family moved from New Orleans to Chicago in 1894. The group included the artist’s paternal grandmother, Emily Motley, pictured here. Her son, Archibald Motley Sr., worked as a Pullman porter on the Michigan Central Railroad and his wife, Mary L. Motley, was a schoolteacher. Their professions were among the highest-status and best-paying jobs black Americans could hold at the time and situated the family in the middle class. The family’s move anticipated the northward Great Migration of African Americans that gained momentum during World War I and continued until the civil rights era.

The artist was among the first African Americans to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (from 1914 to 1918), where he also worked as a janitor to defray costs. Following graduation, Motley elected to focus his art on themes around black American life. This portrait of his grandmother, who was born into slavery in Kentucky in 1842, is venerable and dignified, the effects of time and hard work visible on her hands and face. She lived until age 87. The work, completed when Motley was still an unknown, may have been painted on a cast-off Central Railroad laundry bag from his father’s train line.

Archibald John Motley Jr., Portrait of My Grandmother, 1922, oil on canvas, Patrons' Permanent Fund, Avalon Fund, and Motley Fund, 2018.2.1

Hale Woodruff, alongside Aaron Douglas, Richmond Barthé, and Archibald John Motley Jr., is among the major visual artists of the Harlem Renaissance. Robert Blackburn, an African American artist also credited for this work, founded the Printmaking Workshop in New York, where he taught lithography and printed editions for artists, such as this one. All of the aforementioned artists were born and lived outside New York, but ultimately relocated to Harlem, drawn by its magnetic art scene. In so doing, they joined many African Americans in the northward exodus that became known as the Great Migration. Woodruff studied art at Harvard University and at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, as well as working in Paris, where he embraced modern styles of painting. In addition, he studied with Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, whom he admired for the social justice themes he pursued in his art.

Sunday Promenade, part of a series of work Woodruff made while living in Atlanta during the Depression, depicts two couples and a woman wearing their Sunday best. A church lies behind them in a point at the top of the composition and underscores the centrality of spiritual life in the African American community. The turned-out appearance of the promenaders contrasts with the modest wooden structures also pictured. Woodruff also made politically charged work that dealt graphically with lynching, an issue he felt compelled to confront with his art. During the first part of the 20th century, the NAACP and other groups worked to advance anti-lynching legislation, which was never passed.

Hale Woodruff, Robert Blackburn, Sunday Promenade, published 1996, linocut in black with chine-collé on wove paper, Corcoran Collection (Gift of E. Thomas Williams, Jr. and Auldlyn Higgins Williams in memory of Thurlow Evans Tibbs, Jr.), 2015.19.3032.8

James Van Der Zee opened the Guarantee Portrait Studio in Harlem in 1917. He captured the faces and lives of people who lived in Harlem: its famous entertainers, artists, leaders, and a growing black middle class. He also took his camera to the places they called their own: homes, billiard halls, barbershops, churches, and clubs. Van Der Zee’s work forms an important chronicle of black life of the period. This well-dressed family was associated with Marcus Garvey’s movement, the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). UNIA advocated for black Americans (and others from the African diaspora) to emigrate to Africa to populate and further develop Liberia, the only non-colonial state on the continent. Van Der Zee was hired by the UNIA to record and document its marches, parades, and members, who adopted a quasi-militaristic appearance. The UNIA became a mass movement of over 200,000 members during the 1920s, a time when the Ku Klux Klan had reemerged as a white nationalist group. Garvey was convicted of mail fraud in 1927 and deported to his native Jamaica. Absent his leadership, the movement faded.

James Van Der Zee, Garveyite Family, Harlem, 1924, gelatin silver print, printed 1974, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Eric R. Fox), 2015.19.4388

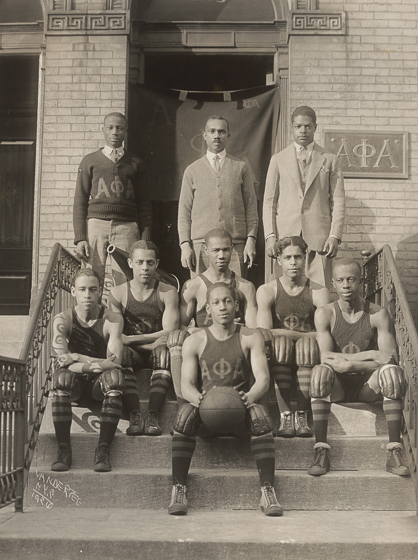

This portrait of a college basketball team shows a serious group of young men united by their affiliation with their fraternity and its basketball team. Alpha Phi Alpha was the first intercollegiate African American fraternity in the United States, its first chapter founded in 1906 at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. The fraternity provided support, study groups, and, later, opportunities to participate in intercollegiate sports at a time when black players were not permitted on college teams. Note how each player is carefully posed and forms a symmetrical arrangement on the steps of the fraternity, showing their integrity as a group while radiating their determination to succeed in a racially divided country.

James Van Der Zee, Alpha Phi Alpha Basketball Team, 1926, gelatin silver print, Corcoran Collection (The Evans-Tibbs Collection, Gift of Thurlow Evans Tibbs, Jr.), 2015.19.4507

Like Aaron Douglas, Norman Lewis was attuned to the importance of jazz and blues music, especially growing up in Harlem during the heyday of the Harlem Renaissance. Only 19 when he created this print, the work shows a modern, abstract quality while capturing visually the sense of music produced by this quartet of musicians, who seem to bob in the space of the picture, emulating the rhythm of the music.

Lewis was influenced by the writings of Alain Locke, an intellectual, impresario, and leader of the Harlem Renaissance who advocated for black visual artists to explore the distinctive character of their experience and culture. Jazz is a hybrid art form with many influences, including West African music. In 1935, Lewis viewed African Negro Art, an early American exhibition (at the Museum of Modern Art, New York) of African sculpture, textiles, and objects shown as aesthetic works of art rather than ethnographic artifacts. Lewis then began a phase of drawing imagined African masks (see the associated Pinterest board for an example). The masklike appearance of the figures in this work may also have been influenced by the exhibition.

Lewis’s printmaking activity over the course of his career was limited; he made prints for the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (FAP) during the Depression years and several editions independently in the 1940s, after which he returned to printmaking only sporadically. After the 1940s, Lewis embraced abstraction in his art and became well-known in the 1950s and beyond for his large-scale paintings, one of which is also in the National Gallery of Art collection (see the related Pinterest board). He is also notable among the artists who took part in the FAP—as printmakers, muralists, and teachers—who later became prominent abstract artists, including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Jacob Lawrence.

Norman Lewis, Jazz, c. 1938, lithograph in black on wove paper, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Florian Carr Fund and Gift of the Print Research Foundation, 2008.115.193

Isac Friedlander, a white printmaker who emigrated to the United States in 1929, reminds us that the Harlem Renaissance and its exuberant nightlife was also an attraction for progressive-minded whites who traveled to Harlem to partake of the entertainment, which was generally entirely produced, written, and performed by black artists and impresarios. Here a top-hatted bandleader leads a group of robed singers, a jazz orchestra, and a pianist in a vibrant musical event. The technique of wood engraving that Friedlander used is a process in which the artist uses negative, or white, lines to describe the image (think of drawing on a black scratchboard). The technique can produce nuanced detail due to the very fine-grained wood that is used for the process. The nature of the medium allowed Friedlander to capture the feeling of a dark nightclub with the performers’ faces illuminated by stage lights. This dynamic scene may have been captured by Friedlander prior to the onset of the Depression.

Isac Friedlander, Rhapsody in Black, 1931, wood engraving, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.1943

This is an image that documents a 1914 gallery exhibition of sculptures by Constantin Brancusi, a Romanian modernist who worked in Paris and was greatly influenced by the forms of African art. At this time, West African art was being imported to the United States by French and Belgian art dealers. This art had come to the attention and interest of artists working in Paris at the beginning of the 20th century, including Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Gauguin, Amedeo Modigliani, Brancusi, and others, who were searching for new forms to express the modern era and a new century. They found inspiration in the often abstract and stylized forms of African art, as well as the art of other non-Western cultures and of antiquity. The relationship of Europeans to the art of Africa entails a complex dynamic that raises questions about who has the right to appropriate and interpret another culture’s patrimony. A generation after the Parisian modernists, the artists of the Harlem Renaissance also borrowed from the forms of African art as a means of reconnecting with and expressing pride in their African heritage.

Alfred Stieglitz, Brancusi Exhibition at 291, 1914, printed 1924/1937, gelatin silver print, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.353

Many Europeans assimilated influences from African art, including Spanish artist Pablo Picasso, who often worked in Paris

At left, the modeled and cast head of Picasso’s companion, Fernande Olivier, is in a cubist mode. Cubism shattered ideas of how space and objects could be depicted in art. For the first time, art was not trying to reproduce the appearance of a person or object. Instead, objects and the subjects of portraits, like this one, were fractured into smaller planes and surfaces. Cubism was meant to portray the artist’s way of seeing and perceiving the subject. Modern artist David Hockney has noted, “Cubism was an attack on the perspective that had been known and used for 500 years. It was the first big, big change. It confused people: they said, ‘Things don’t look like that!’” Some of Picasso’s inspiration for cubism derived from his interest in African art, and particularly masks, which he collected and kept in his studio in Paris.

Pablo Picasso, Head of a Woman (Fernande), model 1909, cast before 1932, bronze, Patrons' Permanent Fund and Gift of Mitchell P. Rales, 2002.1.1

Amedeo Modigliani, an artist from Italy, also worked in Paris, a vibrant cultural capital that attracted young artists from all over Europe. His work does not embrace cubism, but he abstracted the features of his Head of a Woman by elongating them, perhaps in emulation of African masks or archaic sculpture. In turn, artists of later generations, such as those of the Harlem Renaissance, became interested in both the values of modern art, which rejected the art styles and traditions of the past, and in African art, which developed along a distinct trajectory independent of Europe.

Amedeo Modigliani, Head of a Woman, 1910/1911, limestone, Chester Dale Collection, 1963.10.241

This work of art was among some 600 presented in a 1935 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, entitled African Negro Art. The exhibition marked the first time that non-Western cultural objects were shown in a modern art gallery as aesthetic art objects rather than ethnographic artifacts. In so doing, the museum acknowledged the significant influence of African art, traded from colonized African countries, on Western modern art.

Walker Evans, Figure of a Woman, Laongo, 1935, gelatin silver print, Gift of Samuel and Marilyn Stern, 1991.119.17

In 1935, the Museum of Modern Art in New York presented the exhibition African Negro Art. The exhibition’s emphasis on the objects’ aesthetic qualities led the museum to omit information about their cultural context and ceremonial use or significance, which prevented visitors from accessing a deeper understanding of the objects’ origins. For example, the title of this mask does not offer cultural information, such as the fact that it is from Gabon or the Republic of the Congo, Kwele people. What can you discover about art from West Africa and its characteristics?

Walker Evans, Polychrome Mask, 1935, gelatin silver print, Gift of Samuel and Marilyn Stern, 1991.119.6

Today, the Pahouin culture referred to in this object’s title is more commonly known as Fang or Fãn, a Central African ethnic group.

The Museum of Modern Art’s 1935 exhibition, African Negro Art, was photographed by Walker Evans, who may be best known for his photography documenting the effects of the Depression in rural America. Evans produced a portfolio containing 477 prints of African Negro Art; most of these sets were given to African American colleges and universities in the United States.

Walker Evans, Figure of a Young Woman, Pahouin, Border of Spanish Guinea, 1935, gelatin silver print, Gift of Samuel and Marilyn Stern, 1991.119.10