Jacopo Bassano: The Miraculous Draught of Fishes

The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, 1545, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.21.1

The Story

The painting depicts a story from the New Testament in which Jesus calls Peter to become a disciple. The story (Luke 5:1-11) of the miraculous draught (haul) of fishes begins on the shores of Lake Gennesaret, where throngs of followers pleaded with Christ to speak to them. He stepped into a boat and asked to be rowed out into the water. There he preached to the crowds. The boat belonged to two fishermen, Peter and his brother Andrew.

The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, 1545, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.21.1

After he had finished speaking, Christ told Peter to fish. “We toiled all night and took nothing,” Peter responded, “but at your word I will let down the nets.” Suddenly fish poured in, nearly tearing the nets. Peter and Andrew called their partners, James and John, sons of Zebedee, for help. Both boats overflowed with fish. It was a “miraculous draught of fishes.”

The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, 1545, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.21.1

After he had finished speaking, Christ told Peter to fish. “We toiled all night and took nothing,” Peter responded, “but at your word I will let down the nets.” Suddenly fish poured in, nearly tearing the nets. Peter and Andrew called their partners, James and John, sons of Zebedee, for help. Both boats overflowed with fish. It was a “miraculous draught of fishes.”

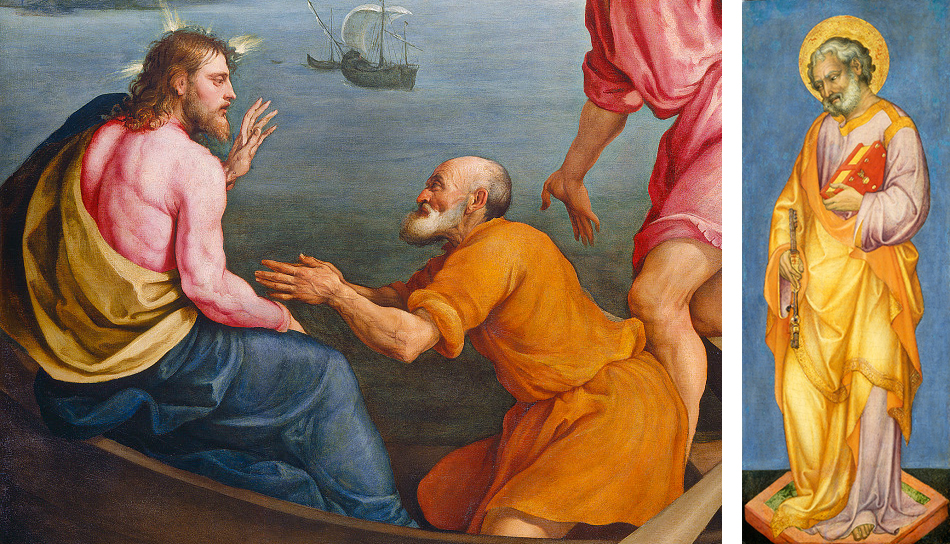

(left) The Miraculous Draught of Fishes (detail), 1545, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.21.1

(right) Michele Giambono, Saint Peter, probably c. 1440, tempera on panel, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress Collection 1939.1.80

The Image

In 1545, the governor of the provincial town Bassano del Grappa commissioned Jacopo to paint The Miraculous Draught of Fishes. Jacopo, however, did not invent the image. He looked to earlier depictions of the story for ideas. This was standard practice in the Renaissance and, in fact, Jacopo's painting was one in a long line of "copies," or variations on a theme.

Duccio di Buoninsegna, The Calling of the Apostles Peter and Andrew, 1308/1311, tempera on panel, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1939.1.141

Thirty years earlier the celebrated artist Raphael had been commissioned to make a tapestry design (or cartoon) depicting The Miraculous Draught of Fishes. As the subject for his work, he chose the moment when Peter confesses his sinfulness to Christ. Raphael adopted the motifs of two boats overlapping and Peter kneeling before Christ from earlier images.

Raphael, The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, 1515, cartoon, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Jacopo's Miraculous Draught of Fishes is based on Raphael's composition, but he never actually saw that work. His source was a chiaroscuro woodcut [1] copy of Raphael's cartoon made by an artist named Ugo da Carpi.

Prints that reproduced paintings became extremely important during the Renaissance (and remained so until the invention of photography) because they allowed artists in distant cities to study each other's work. Jacopo relied heavily on prints; he lived in a small town and could not travel to Rome and Florence, Italy's great artistic centers. He only infrequently went to Venice, even though it was nearby. Instead, he developed a large collection of prints, which he studied closely and from which he developed his images.

1. Chiaroscuro means light and dark in Italian. The chiaroscuro woodcut technique was developed so that highlights and shading—light and dark—could be added to a linear image. Making these prints required several steps. The paper was usually tinted with a colored wash. An artist such as Ugo da Carpi would have carved several blocks out of wood: the first was printed in black ink and gave the outlines of the image; a second was printed in a lighter color to create highlights; and sometimes additional blocks were carved for more colors and highlights. Ugo da Carpi specialized in chiaroscuro woodblock prints. Diogenes, is considered to be his masterpiece.

Ugo da Carpi after Raphael, The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, unknown date, chiaroscuro woodcut, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna

For The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, Jacopo copied many elements directly from Ugo da Carpi: the figure groupings, their positions, actions, garments, and even the oar projecting from beneath Andrew's legs are taken nearly exactly from the original, though in reverse.

(top) Ugo da Carpi after Raphael, The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, unknown date, chiaroscuro woodcut, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna

(bottom) Jacopo Bassano, The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, 1545, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.21.1

Jacopo, however, altered the composition in subtle but significant ways. While Ugo da Carpi's figures move diagonally into the middle ground, Jacopo's figures are brought forward, parallel to the picture plane. They are also larger in relation to the background—Andrew spans the entire height of the canvas. These changes give the painting a monumentality that would have been lacking if Jacopo had transferred the print's composition exactly.

(left) Jacopo Bassano, The Miraculous Draught of Fishes (detail), 1545, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.21.1

(right) Ugo da Carpi after Raphael, The Miraculous Draught of Fishes (detail), unknown date, chiaroscuro woodcut, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna

By lowering James and John so that they are kneeling in the boat, and adding Andrew's brilliant, billowing cape, Jacopo builds his composition around dynamic sweeping curves.

(right) Jacopo Bassano, The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, 1545, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.21.1

(left) Ugo da Carpi after Raphael, The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, unknown date, chiaroscuro woodcut, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna

Jacopo's painting reflects the influence of mannerism. Derived from the Italian word maniera, or "style," mannerist painting emerged in central Italy around 1520 and had spread to Venice by 1540. Jacopo knew the work of mannerist artists such as Pontormo, Parmigianino, and Tintoretto, as well as printmakers like Marcantonio Raimondi, who often reinterpreted important sixteenth-century Italian paintings.

(top left) Pontormo, Deposition, 1526-1528, oil on panel, Capponi Chapel, Church of Santa Felicita, Florence

(top middle) Parmigianino, Madonna with the Long Neck, 1535, oil on panel, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

(top right) Jacopo Tintoretto, Christ at the Sea of Galilee (detail), c. 1575/1580, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1952.5.27

(bottom left) Agnolo Bronzino, Holy Family, c. 1527/1528, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1939.1.387

(bottom right) Marcantonio Raimondi after Raphael, Massacre of the Innocents, unknown date, engraving, Print Purchase Fund (Rosenwald Collection), 1975.54.1

Exaggerated forms, compressed space, and intense color are mannerist features Jacopo used to heighten the drama of the scene. Jacopo is less interested in naturalism than in creating forceful designs on the canvas. This artificiality can be seen in such elements as Christ's transparent shirt, which reveals his strength and muscularity.

The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, 1545, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.21.1

The brilliant hues, which account for much of the painting's aesthetic appeal, are Jacopo's invention. High-toned colors—rose, orange, and green—weave across the surface, creating an undulating rhythm.

The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, 1545, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.21.1

Two additions may have been made for the painting's patron, Pietro Pizzamano, governor of the town of Bassano del Grappa—the view of the town and Monte Grappa just behind it, which, in reality, were not situated together.

Jacopo finished the painting in 1545. Like most provincial governors, Pizzamano was a Venetian aristocrat. When he finished his term in Bassano, he took this painting with him to hang in his family's palazzo in Venice. Many of the city's artists, including its most famous, Titian, came to see this work by a painter of whom they knew little.

The Miraculous Draught of Fishes (detail), 1545, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.21.1

Venice was one of the wealthiest and most powerful city-states in Renaissance Europe, and Venetian painting was renowned for its sumptuous color and sensuous textures. Jacopo Bassano was one of the four leading painters of this period but he is less well-known today than his contemporaries Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto.

Canaletto, Ascension Day Festival at Venice, 1766, pen and brown ink with gray wash, heightened with white, over graphite, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1963.15.5

Venetian paintings—indeed most Renaissance paintings—were produced in workshops, often family businesses that continued for generations. Jacopo Bassano was part of such a family workshop. He was born in 1510 in the small, prosperous town of Bassano del Grappa, located about thirty miles west of Venice. The family shop and home were located near the town's wooden bridge, hence their name "Dal Ponte" (of the bridge).

(left) Bassano del Grappa with Palladio's Bridge, photograph by Leo J. Kasun

(right) Bassano del Grappa with Palladio's Bridge (detail), photograph by Leo J. Kasun

From the age of thirteen, Jacopo trained in his father Francesco's workshop. His brother, Giambattista, joined the shop, and later his own sons, Francesco, Giovanni Battista, Leandro, and Gerolamo, all became painters. Like any apprentice, Jacopo learned many skills: carpentry, terracotta, grinding and mixing paints, preparing canvases, and the art of painting itself. He had no formal education, but he could read, write, and keep financial accounts. He also trained briefly in the Venetian workshop of Bonifazio de' Pitati.

Parmigianino, A Painter's Assistant Grinding Pigments, 1535, chalk drawing, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The da Ponte workshop was a bustling factory—the family produced thousands of paintings over the years. Jacopo was the most talented artist, but after his death his reputation suffered because critics could not differentiate his works from those by other family members, many of whom were not accomplished painters. Today scholars have distinguished about two hundred paintings for which Jacopo was mainly responsible.

Leandro Bassano, Portrait of Jacopo Bassano da Ponte, c. 1590, oil on canvas, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, photograph by Erich Lessing

Jacopo was known for his mannerist paintings, such as The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, which are richly colored with rhythmic groupings of muscular figures. But he is also celebrated for his ability to synthesize seemingly incompatible approaches to painting. His work is both artificial and natural, elegant and earthy. Later in his career, he perfected a kind of "biblical genre" painting that became extremely popular with collectors, for example, Christ in the House of Mary, Martha, and Lazarus. He also painted more loosely and expressively, using darker colors. His contemporaries praised his ability to portray night scenes and the elements of everyday life—pots and pans, farm animals, and peasants.

Jacopo and Francesco Bassano, Christ in the House of Mary, Martha, and Lazarus, 1576, oil on canvas, Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation, Houston, inv. 79.13