The Art of Power: Royal Armor and Portraits from Imperial Spain

The Art of Power: Royal Armor and Portraits from Imperial Spain

Royal armor in the Renaissance was far more than protective equipment for the battlefield. Most often worn at court ceremonies and in parades, pageants, and jousting tournaments, it proclaimed the rulers' strength and power. Elaborately decorated with imagery drawn from history, mythology, or the Bible, armor symbolically presented emperors and kings as the new Caesar, the equal of Hercules and other ancient heroes, the defender of the faith, or the model of chivalry. Etched or engraved images of saints or the Virgin and Child asserted that the rulers enjoyed divine protection. Much more costly than portraits by the leading painters of the day, suits of royal armor are dazzling works of wearable sculpture that affirmed their owners' right to govern.

Desiderius Helmschmid, German, documented 1513–1579, Equestrian Armor of Emperor Charles V, Augsburg, c. 1535–1540 (lance, 16th-19th century) etched, embossed, and gilt steel, brass, leather, fabric (lance: steel and wood), Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

The Art of Power presents many of the most splendid suits of armor, helmets, shields, and equestrian armor from the Royal Armory in Madrid. One of the finest collections of armor in the world, it was created by Spanish members of the Habsburg dynasty that ruled much of Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries. Armor once belonging to Holy Roman Emperors and Spanish monarchs is exhibited alongside tapestries and paintings show the armor in use. Several suits of armor are paired with portraits by Alonso Sánchez Coello, Anthonis Mor, Diego Velázquez, Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony Van Dyck, and other artists who depicted rulers wearing the same armor.

Italian, 16th Century, Shield, Milan, c. 1565–1570, gold- and silver-damascened steel, leather, fabric, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

The Order of the Golden Fleece

The most prestigious chivalric order was that of the Golden Fleece, founded in 1430 by Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy, to defend the Christian faith and "exalt the noble order of knighthood." In the sixteenth century, membership was limited to the sovereign plus fifty knights from royal or noble families. The order's insignia, a ram's fleece worn suspended from a collar or necklace, alludes to the mythical quest of the Greek hero Jason to seize the Golden Fleece, guarded by a dragon on the Black Sea.

Because Jason's success enabled him to regain his rightful place as king of Iolcus in Thessaly, the Golden Fleece became associated with kingship. One of the principal symbols of power associated with the Spanish crown since the later 15th century, it appears frequently on the armor, including the helmet of Philip the Good's great-grandson, Charles V.

Narciso Soria, silversmith and jeweler, Spanish, documented between 1800 and 1854, Collar of the Order of the Golden Fleece, Madrid, 1854, Gold and gilt silver, blue and white enamel, Patrimonio Nacional, Palacio Real de Madrid

This striking parade helmet is also a portrait of Charles V, who was noted for his golden-red hair. Its maker, Filippo Negroli, is considered the greatest Italian armorer of the Renaissance, famed for his designs based on the art of antiquity. He may have known similar ancient Greek or Roman portrait-helmets from surviving examples or, more likely, from their depiction in antique sculpture. The three small holes around the opening are for the attachment of a plate, now missing, that completed the upper part of the face.

Filippo Negroli, Italian, c. 1510–1579, Parade Helmet of Emperor Charles V, Milan, 1533, Embossed and gilt steel, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

Spain and al-Andlaus

For most of the fifteenth century, Spain was divided into the kingdoms of Castile and Leon, Aragon, and Navarre, with the Muslim emirate of Granada in the south. The Muslim presence in Spain dates to the 8th century, when it rapidly extended over most of the Iberian Peninsula. The Christian reconquest of Toledo in 1085 reduced al-Andalus to the southern half of the country.

The intellectual heart of al-Andalus, or Muslim Spain, had long been Cordoba, a center of advancements in science, philosophy, history, and the arts, as well as the first city in Europe to provide public libraries and modern amenities such as street lamps for nighttime illumination. The unification of Spain began with the marriage of Isabella, Queen of Castile, and Ferdinand, King of Aragon, in 1469. During their reign, the Spanish reconquest of the peninsula concluded with the fall of Granada in 1492. By the mid-13th century, nearly constant warfare with the Christian kingdoms to the north had shrunken Muslim-controlled territories to the region around Granada, ruled by the Nasrid dynasty under which the palatial fortress of the Alhambra was built.

Iberian Peninsula in the Mid-14th Century

Mary is portrayed as the Virgin of Mercy who spreads her cloak to shelter the faithful from the dangers of sin, symbolized by two demons hurling arrows. At left, Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile appear with their children and a cardinal. At right, a group of Cistercian nuns is led by an abbess, probably Leonor de Mendoza, the cardinal’s sister. She was the founder of the convent of Las Huelgas in Burgos, which still owns this altarpiece.

Diego de la Cruz and Workshop, Spanish, active between 1482 and 1500, The Virgin of Mercy with the Family of the Catholic Monarchs, c. 1486, oil on panel, Patrimonio Nacional, Monasterio de Santa María la Real de las Huelgas de Burgos

This finely worked enameled sword is a trophy of war, captured in battle against the forces of Muhammad XII, the last Nasrid ruler of Granada. He was known as Boabdil (a corruption of Abu Abdullah, his given name) by the Spanish.

Spanish, 15th Century, Sword and scabbard of Boabdil (Muhammad XII), Nasrid Granada, c. 1400, Steel, gold, enamel, metal wire, ivory, leather, wood, Museo del Ejército, Toledo

Maximilian I

Maximilian I was Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death in 1519, having previously ruled jointly with his father, Frederick III. The Holy Roman Empire arose from the ruins of the Carolingian empire of Charlemagne, which splintered following his death in 814. The eastern portion encompassing the German-speaking lands of central Europe developed into the Holy Roman Empire, which from the 15th century onward was ruled almost exclusively by members of the House of Habsburg. Originally from Switzerland, the Habsburgs governed from Austria after 1278. They began expanding their dominions when Maximilian's marriage to Mary of Burgundy in 1477 brought the Duchy of Burgundy and the Netherlands under Habsburg control. Spain became part of the empire after their son, Philip the Handsome, married the daughter of the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella in 1496.

Hans Burgkmair I, German, 1473 - 1531, Emperor Maximilian I, 1508/1518, chiaroscuro woodcut in green printed from two blocks, Rosenwald Collection, 1948.11.14

Maximilian commissioned works of art and armor that conveyed his imperial status. The monumental woodcut by Albrecht Dürer and his workshop evokes the triumphal arches constructed in ancient Rome in honor of victorious emperors. On either side, scenes of successful battles and dynastic marriages announce Maximilian's military and diplomatic prowess. The central portion depicts a family tree purporting to trace his genealogical descent from Hector of Troy, Julius Caesar, and Clovis, the founder of the French royal dynasty.

Albrecht Dürer, German, 1471 - 1528, The Triumphal Arch of Maximilian, 1515 (1799 edition), 42 woodcuts and 2 etchings on laid paper assembled to form one image, Gift of David P. Tunick and Elizabeth S. Tunick, in honor of the appointment of Andrew Robison as Andrew W. Mellon Senior Curator, 1991.200.1

Maximilian's equestrian armor portraying feats of strength by Hercules and Samson, also presents him as the successor to heroes of antiquity.

Attributed to Kolman Helmschmid, German, 1470–1532, Equestrian Armor of Maximilian I, Augsburg, c. 1517–1518, openwork, embossed, etched, and gilt steel; fabric and leather, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

The son of Maximilian, Philip was born in the Burgundian Netherlands (modern Belgium), which he had inherited from his mother. After his marriage in 1496 to Joanna ("the Mad"), daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, he became Philip I of Castile, the first Habsburg ruler in Spain. This portrait is the earliest known representation of an armor-clad king of Spain. Philip’s surcoat, worn under his coronation robe and over his armor, bears the arms of the Spanish kingdoms and Burgundy.

Master of the Joseph Sequence, Netherlandish, active c. 1490–1505, Philip the Handsome, 1504–1506, oil on oak panel, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels

Charles V

The grandson of Maximilian and son of Joanna ("the Mad") of Castile, Charles became king of Spain, where he ruled as Charles I, in 1516. Three years later he was elected Holy Roman Emperor, reigning as Charles V from 1519 to 1556. He was then the most powerful man in Europe, with domains extending across central Europe, the Netherlands, Flanders, Burgundy, Spain, the Duchy of Milan, the Kingdom of Naples, enclaves in North Africa, and much of the Americas.

Anonymous Artist, Charles V at Age Seven with a Sword, c. 1508, oil on panel, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Gemäldegalerie

(top) Map of the Holy Roman Empire under Charles V

(bottom) Map of imperial coats of arms of Charles V

Before ascending to the Spanish throne, Charles lived in the Burgundian Netherlands, where he had been born in 1500. Raised there by Maximilian's daughter, he shared his grandfather's preference for German armorers. Charles' patronage of Kolman and Desiderius Helmschmid of Augsburg brought them fame and set a fashion for elegant armor in which smooth surfaces alternate with vertical bands of gilded and engraved decoration. As a result of his conquest of the Duchy of Milan in 1525, Charles also gained access to the renowned workshop of Filippo Negroli, the sole armorer mentioned by Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of the Artists of 1550. Charles' lavish commissions made the Royal Armory one of the greatest repositories of German and Italian armor in existence.

Desiderius Helmschmid, German, documented 1513–1579, Helmet of Emperor Charles V, Augsburg, c. 1540, Embossed, etched, and gilt steel, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

Armor with a tonlet, or flaring skirt, was designed for combat on foot within an enclosed field, a tournament sport in which swordsmen were awarded points according to the quantity and location of the blows they dealt. Decorated with a hunting scene showing a bear, deer, and wild boar chased by hounds, this ensemble has been known as the "Hunt Tonlet" armor since the sixteenth century.

Kolman Helmschmid, German, c. 1470–1532, Armor of Emperor Charles V, Augsburg, c. 1525, etched and gilt steel, leather, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

Desiderius Helmschmid, German, c. 1513–1579, Armor of Emperor Charles V, Augsburg, c. 1525, etched and gilt steel, leather, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

Because of the decoration over the elbows, shoulders, and helmet, this armor is known as the "Mask Garniture." (Garnitures are sets of armor with interchangeable parts that adapted the suit for use on horseback or on foot, in tournaments or on the battlefield.) It is the only suit of armor signed and dated by Filippo (in an inscription under the visor) and is thus considered the key work of the Negroli workshop. The exquisite damascening, a technique for inlaying the gold designs, is the work of Filippo’s talented seventeen-year-old brother, Francesco.

Filippo Negroli and Brothers, Italian, c. 1510–1579, Armor of Emperor Charles V, Milan, 1539, embossed and gold- and silver-damascened steel; brass and leather, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

Anonymous Netherlandish, Charles V with Raised Sword, second half of the 16th century, oil on panel, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial

Philip II and the Royal Armory

The Royal Armory was created by Charles V's son, Philip II, whose long reign as king of Spain lasted from 1556 to 1598. His wills stipulated that his collection could not be dispersed after his death, but should instead be handed down to his descendents. Philip's great respect for his father and for the material and symbolic value of the emperor's armor led him to purchase Charles' collection, which had been slated for sale to pay off outstanding debts at the time of his death in 1558. Armor made for subsequent monarchs was later added to those two core collections.

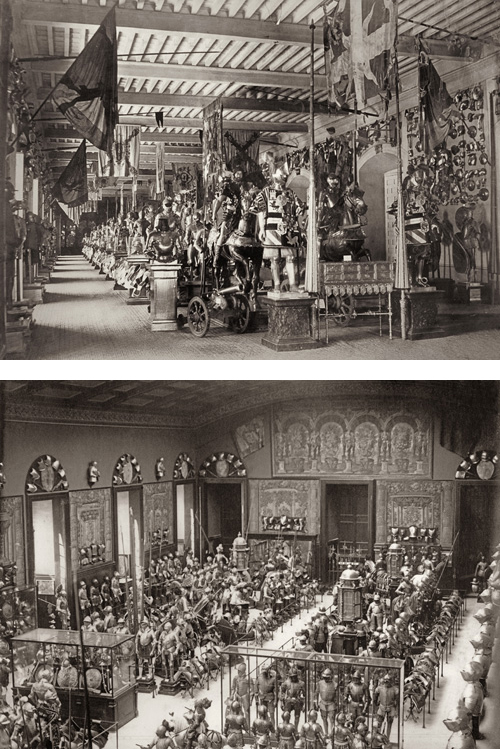

(top) View of the Armory c. 1884

(bottom) View of the Armory c. early 20th century

Unlike arsenals, which keep weapons and armor to equip an army for battle, the Royal Armory includes trophies of war as well as armor received as diplomatic gifts or worn in pageants, parades, and tournaments. The process of decorating such armor, often by embossing or hammering the steel from the reverse to create designs in relief, weakened the metal. The armor is consequently more propagandistic than utilitarian, serving to impress viewers with its opulence and imagery extolling the wearer's power, valor, and chivalry.

(left) Italian, 16th Century, Helmet (Burgonet) of Philip II, Milan, c. 1560–1565 embossed, gold- and silver-damascened steel, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

(right) Kolman Helmschmid, German, c. 1470–1532, Helmet (Burgonet) of Emperor Charles V, Augsburg, c. 1530, etched, embossed, and gold-damascened steel; fabric and leather, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

Ancient wars were a popular subject for Renaissance parade armor, as on this shield and burgonet (an open-faced helmet) depicting scenes from the Trojan War. The left side of the helmet shows the Judgment of Paris, the Trojan prince who declared Aphrodite the most beautiful goddess after she promised him Helen, wife of the king of Sparta. On the right side, Trojans tear down part of their city walls to make way for the huge Trojan horse in which Greek warriors were hidden. Paris’ abduction of Helen and the Greeks’ departure for Troy appear in the center of the shield.

Italian, 16th Century, Helmet (Burgonet) of Philip II, Northern Italy, c. 1560–1565, gold- and silver-damascened steel, fabric, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

This masterpiece of the Negroli workshop was made from a single sheet of steel that was hammered out from the underside in a technique known as embossing or repoussée (French for "pushed out"). A Turkish soldier with bound arms arches over the top of the helmet, while two female figures personifying Fame and Victory grasp his mustache. The scene symbolizes victory over Islam and Charles’ role as defender of the Christian faith. The inscription compares him to "Invincible Caesar."

Filippo and Francesco Negroli, Italian, c. 1510–1579 and c. 1522–1600, Helmet (Burgonet) of Emperor Charles V, Milan, 1545

embossed and gold-damascened steel, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

Designed by the Italian painter Giulio Romano, this richly symbolic scene celebrates Charles V's triumphs. The emperor stands at the prow of a ship, gripping a standard on which the double-headed imperial eagle perches. Fame holds a shield inscribed with his motto, "Plus Ultra" (Further beyond), while overhead, winged Victory crowns him with a wreath of laurel. The sea god, Neptune, at far left and the Pillars of Hercules refer to Charles' territories beyond the Straits of Gibraltar. Below, the river god Quadalquivir reclines next to a bound female captive, personifying Africa. Like the adjacent pillar topped by a turban, she alludes to the emperor’s victories over the Ottoman Turks.

Italian, 16th Century, Parade Shield with the Apotheosis of Charles V, Italy, c. 1535–1540, etched and embossed steel; gold and silver, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid,

The scene as the Roman conquest of Carthage in 146 BC depicted on the helmet, paralleled Charles V's victory over the Ottoman Turks at the North African port of Tunis, near ancient Carthage. Like the Romans and Carthaginians, the Habsburgs and Ottomans vied for control of the Mediterranean Sea.

Italian, 16th Century, Shield of Philip II, Milan, c. 1560–1565 embossed, gold- and silver-damascened steel, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

Ancient wars were a popular subject for Renaissance parade armor, as on this shield and burgonet (an open-faced helmet) depicting scenes from the Trojan War. The left side of the helmet shows the Judgment of Paris, the Trojan prince who declared Aphrodite the most beautiful goddess after she promised him Helen, wife of the king of Sparta. On the right side, Trojans tear down part of their city walls to make way for the huge Trojan horse in which Greek warriors were hidden. Paris' abduction of Helen and the Greeks' departure for Troy appear in the center of the shield.

Italian, 16th Century, Shield of Philip II, Northern Italy, c. 1560–1565, gold- and silver-damascened steel, fabric, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

Gift of the Duke of Savoy to Philip III

This intricately worked helmet and shield and the armor for a horse are from a spectacular parade garniture (a set of armor) probably commissioned by the Duke of Savoy on the occasion of his marriage to a daughter of Philip II in 1585. Eighteen years later, it was presented to Philip III as a gift from the duke, which his sons delivered to the king when they were sent from their native Turin to Madrid to be educated at the Spanish court.

The chanfron protected the horse's face, while the crinet guarded the back of the neck.

(left) Italian, 16th Century, Chanfron and Crinet from the Garniture Presented by the Duke of Savoy to King Philip III, Milan, c. 1585, etched, embossed, gilt, and gold-damascened steel, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

(right) ItaIian, 16th Century, Tail Guard from the Garniture Presented by the Duke of Savoy to King Philip III, Milan, c. 1585, etched, embossed, gilt, and gold-damascened steel, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

The garniture has lost some of its original splendor as it now lacks the gemstones, cameos, and crystals that enhanced its lavish decoration. The helmet, crowned with a sphinx, depicts Romulus and Remus, the twin founders of ancient Rome, and the fall of Phaeton, who drove the chariot of the sun too close to the earth, threatening to set the world afire.

Italian, 16th Century, Helmet (Burgonet) from the Garniture Presented by the Duke of Savoy to King Philip III, Milan, c. 1585, etched, embossed, gilt, and gold-damascened steel; silver and fabric, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

In the center of the shield, Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) tames the wild horse Bucephalus in the presence of his father, Philip II of Macedon. Armor of this sort combines the chivalric spirit of the late Middle Ages with new Renaissance imagery inspired by the revival of classical art and culture.

Italian, 16th Century, Shield from the Garniture Presented by the Duke of Savoy to King Philip III, Milan, c. 1585, etched, embossed, gilt, and gold-damascened steel; silver and fabric, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

The Mühlberg Armor

On April 24, 1547, the Catholic forces of Charles V defeated a league of German Protestants at the Battle of Mühlberg, on the Elbe River east of Leipzig. The victory reaffirmed Charles' authority over rebellious German princes seeking not only religious freedom but also greater autonomy from the Holy Roman Empire. The suit of armor Charles wore at Mühlberg as well as parts of the equestrian armor were used on that occasion.

Desiderius Helmschmid, German, documented 1513–1579, The "Múhlberg Armor" of Charles V, Augsburg, 1544, etched, embossed, and gilt steel, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

Desiderius Helmschmid, German, documented 1513–1579, The "Mühlberg Armor" of Charles V, Augsburg, 1544, etched, embossed, and gilt steel, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

An iconic symbol of imperial power, the Mühlberg armor appears in several portraits of Charles V. Shortly after the battle, the emperor's favorite artist, Titian, created two likenesses of him wearing this armor: a monumental equestrian portrait and a full-length standing portrait. The latter work is now lost, but is known from copies by the Spanish artist Pantoja de la Cruz, considered the definitive version of Titian's original.

Renaissance armor was often patinated to retard rusting, and so appears black in Pantoja's portrait. The "Mühlberg Armor," however, may never have been patinated as it is described as "white" in old inventories. Possibly, Pantoja added the patina for aesthetic reasons so that the gilded decoration stood out against a dark background. In other respects, Pantoja recorded the armor with precision, even including the image of the Virgin and Child on the breastplate and the insignia of the Order of the Golden Fleece around Charles’ neck.

Juan Pantoja de la Cruz, Spanish, 1553–1608, Portrait of Charles V, 1608, oil on canvas, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial

Desiderius Helmschmid, German, documented 1513–1579, Saddle from the "Mühlberg Garniture" of Charles V, Augsburg 1544, etched, embossed, and gilt steel, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

Desiderius Helmschmid, German, documented 1513–1579, Chanfron from the "Mühlberg Garniture" of Charles V, Augsburg, 1544, 1544, etched, embossed, and gilt steel, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

The Burgundy Cross Armor

Philip II wore this armor at the Battle of Saint-Quentin against the French on August 10, 1557, when he won his first victory as king. The armor's association with triumph led the Netherlandish painter Anthonis Mor to portray the king dressed in part of the suit he wore on horseback "as he sallied forth on the day of Saint-Quentin." The same armor appears in Carreño de Miranda's portrait of Charles II, Philip's great-grandson. Both paintings preserve the armor's original blackened surface, which once set off the gilded decoration, but has worn away over the centuries.

(left) Anthonis Mor, Netherlandish, 1519–1576, Philip II in Armor, 1560, oil on canvas, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial

(right) Juan Carreño de Miranda, Spanish, 1614–1685, Charles II in Armor, 1681, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid,

Through marriage, Philip inherited the Portuguese crown and rode into Lisbon on a horse partly outfitted in this armor for his coronation as king of Portugal in 1581. The armor for man and horse had been made for him when he was still a prince by his favorite armorer, Wolfgang Grosschedel of Landshut in Bavaria. The decoration includes the insignia of the Golden Fleece, as well as x-shaped crosses alluding to the cross on which Saint Andrew, the patron saint of Burgundy, was crucified. As a result of the marriage of Philip's great-grandfather, Maximilian, to Mary of Burgundy in 1477, the cross became a Spanish royal emblem.

Wolfgang Grosschedel, German, c. 1517–1562, The "Burgundy Cross Armor" of Philip II, Landshut, 1551, etched and gilt steel; gold and brass, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

The Diet of Augsburg

The Holy Roman emperor was elected by a body of seven German princes and archbishops who met for that purpose at Augsburg in 1550. Charles promoted the candidacy of his son Philip, arranging for him a grand tour of European courts that culminated with his arrival in Augsburg to attend the imperial Diet, or formal assembly. The exquisite suit of armor commissioned for that occasion was probably intended to lend Philip a majestic appearance that would impress the electors. Philip, however, succeeded his father only as king of Spain, for the electors chose Charles' brother Ferdinand, archduke of Austria, to become the next emperor.

Desiderius Helmschmid, German, documented 1513–1579, Jörg Sigman, German, 1527–1601, Parade Armor of Philip II, Augsburg, 1549–1550 and 1552, gilt and damascened steel; brass and leather, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

Desiderius Helmschmid created the extraordinarily sumptuous armor in collaboration with a goldsmith, Jörg Sigman. The elaborate garniture also included an embossed shield, as well as a complete set of equestrian armor, represented here by the chanfron, which covered the horse's face. The suit of armor lacks the original dark patina, still preserved on the shield and chanfron.

Desiderius Helmschmid, German, documented 1513–1579, Jörg Sigman, German, 1527–1601, Chanfron of Philip II, Augsburg, 1549–1550 and 1552, gilt and damascened steel; brass and leather, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

The German shield at left was apparently made in competition with Filippo Negroli, the famed Milanese armorer who specialized in armor with raised, or embossed, decoration. On the upper part of the rim, a bull lunges to gore a warrior holding a tiny shield labeled "Negrol" (written backward)—Helmschmid’s boast that he could surpass his rival. In the circular inscription at the center, Desiderius proudly describes himself as "Armorer to His Imperial Majesty." The four medallions depict the Triumphs of Wisdom, Peace, War, and Strength.

Desiderius Helmschmid, German, documented 1513–1579, Jörg Sigman, German, 1527–1601, Shield of Philip II, Augsburg, 1549–1550 and 1552, gilt and damascened steel; brass and leather, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

The Flower-Pattern Armor

Known since the sixteenth century as the Flower-Pattern Armor, this suit was evidently delivered to Philip II during his extended stay in Augsburg for the imperial Diet.

Desiderius Helmschmid, German, documented 1513–1579, The "Flower-Pattern Armor" of Philip II, Augsburg, c. 1550, etched, embossed, and gilt steel, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

Desiderius Helmschmid, German, documented 1513–1579, Helmet (Burgonet) from the "Flower-Pattern Armor," c. 1550, etched, embossed, and gilt steel, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid,

Peter Paul Rubens' equestrian portrait of the king dressed in this armor was commissioned after his death by his grandson Philip IV (reigned 1621–1665). The artist borrowed the pose of the horse and rider from a portrait of Charles V, but replaced the emperor's face and armor with those of Philip II, basing them on a likeness of the king that Titian had painted from life. Unusually, the royal flower-pattern armor also appears in Velázquez's portrait of a member of the high nobility, Juan Francisco Pimentel, count of Benavente, who was awarded the collar of the Golden Fleece in 1648 in recognition of his military service to the king.

(left) Sir Peter Paul Rubens, Flemish, 1577–1640, Equestrian Portrait of Philip II, c. 1630–1640, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

(right) Diego Rodriquez de Silva y Velázquez, Spanish, 1599–1660, Juan Francisco Alfonso de Pimentel, Count of Benavente, c. 1648, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

Philip III

As the youngest of Philip II's four sons, Philip III (1598–1621) was an unlikely successor to the throne. The presumed heir, the mentally unbalanced Don Carlos, died after he was deemed unfit to rule and two brothers did not survive early childhood. The suits of armor here were made for Prince Philip when he was seven, the year he took the oath as Prince of Asturias, the title for the heir apparent. Because that event relieved fears that the Habsburg dynasty in Spain would come to an end, suits of armor that had belonged to the seven-year-old prince took on special significance. Consequently, they appear in his portraits by Justus Tiel and Pantoja de la Cruz, even though Philip was by then older and would have outgrown the armor. He ascended to the throne in 1598 and ruled until his death at the age of forty-three.

(left) Juan Pantoja de la Cruz, Spanish, 1553–1608, Philip III as a Prince in Armor, c. 1592, oil on canvas, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Gemäldegalerie

(right) Juan Pantoja de la Cruz, Spanish, 1553–1608, Philip III in Armor, 1605, oil on canvas, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial

By the time of Justus Tiel's portrait, Philip was twelve years old and could not have posed wearing the armor. Its imagery probably inspired this painting, which also alludes to the virtues expected of a future king. Tiel portrayed the prince attended by a female figure of Justice who hands him scales and a sword, symbolizing prudence and power; the staff, known as a caduceus, representing peace; and a bridle and reins, suggesting moderation and restraint. Behind them, Chronos (Time) pushes blind Cupid aside and Justice forward. The hourglass with a still-empty lower chamber balanced on Chronos' head signifies the prince's youth.

Justus Tiel, Flemish, active last third of the 16th century, Allegory of the Education of Philip III, 1590, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

The size of the armor indicates that it was made for Philip when he was about seven years old. Its exuberant decoration of masks, grotesques, and military trophies includes an image of the warrior goddess Minerva (in the center of the breastplate), flanked by personifications of Fortitude, standing next to a column, and Prudence, holding a mirror. Other virtues meant to govern the prince's life—Justice and Temperance—are depicted on the backplate. Fame and Victory appear near the top of the breastplate and on the elbow guards.

Attributed to Lucio Marliani, Italian, documented 1538–1607, Child's Armor and Helmet of Philip III, Milan, c. 1585, etched, embossed, gilt, and gold- and silver-damascened steel; brass and fabric, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid,

Both suits of armor shown here were made for young Philip to wear in foot combat at the barrier, a sport introduced in the mid-16th century. Participants wore half-armor, as they fought with wooden swords on opposite sides of a low barrier and blows to the lower body were forbidden. The portrait of the prince at age fourteen by Pantoja de la Cruz, shows him dressed in this same armor and depicts its original patina.

Italian, 16th Century, Child's Armor of Philip III, Milan, c. 1585, etched, embossed, and gilt steel; gold damascening and silver relief work, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

Royal Armor: The Last Phase

The widespread use of firearms and waning popularity of jousting tournaments caused a steep decline in the production of armor in the seventeenth century. Because the symbolic value of armor outlived its effectiveness in battle, sumptuous examples were still made as diplomatic gifts and appeared in portraits of members of the royal family. Gradually, however, royal armor became dissociated from the rulers for whom it had been made. Rather than projecting an image of their their power, the collection of the Royal Armory became a resource for artists seeking elegant models for the armor they depicted in paintings of non-royal subjects, such as Pedro Núñez del Valle's Jael and Sisera.

The Habsburg line in Spain ended in 1700 with the death of Philip IV's son and successor, Charles II. In 1660 Philip's daughter Maria Teresa had married Louis XIV, paving the way for the French House of Bourbon to assume the Spanish throne. Their grandson Philip V was the first of the Bourbon dynasty to rule Spain and the grandfather of Charles III, whose portrait is the last to portray a king of Spain in armor.

Anton Raphael Mengs, German, 1728–1779, Charles III in Armor, c. 1761, oil on canvas, Patrimonio Nacional, Palacio Real de Madrid

As told in the book of Judges, Jael was an Old Testament heroine who rescued the Israelites from the Canaanites. The Israelites, led by Barak, fought against their oppressors with such vengeance that the Canaanite leader, Sisera, fled and sought refuge in Jael's home. She received him with false hospitality, offering him milk and a place to rest, but while he slept, she pounded a nail into his temple. Núñez del Valle depicted the moment when Barak arrives in search of his enemy and finds him dead. The artist based Sisera's armor on the Roman-style suit shown here, and that of Barak on the armor that had been made for Charles V by Desiderius Helmschmid.

Pedro Núñez del Valle, Spanish, between c. 1590 and 1594–1649, Jael and Sisera, c. 1630, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

Roman-style armor recalled the leather cuirasses of antiquity, which imitated a warrior's muscled chest. Although such armor is often depicted in Renaissance tapestries and paintings, this suit is the only complete surviving Roman-style armor in the world. Presented as a gift to Philip II, it served as the model for the armor worn by the fallen figure of Sisera in the painting by Pedro Núñez del Valle.

Bartolomeo Campi, Italian, died 1573, Roman-Style Armor Given to Philip II, Pesaro, 1546, embossed and gold- and silver-damascened steel; brass and fabric, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid,

Emmanuel Philibert was the grandson of Philip II , the cousin of Philip IV, the supreme commander of the Spanish navy in the Mediterranean, and viceroy of Sicily. While living in Palermo, he summoned the Flemish artist Anthony van Dyck, then based in Genoa, to paint this court portrait of him wearing the armor shown here. Executed the year Emmanuel died of the plague at the age of thirty-six, the portrait exemplifies an early seventeenth-century ruler, combining a sense of martial prowess with foppish elegance.

Sir Anthony van Dyck, Flemish, 1599–1641, Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy, Viceroy of Sicily, 1624, oil on canvas, By Permission of the Trustees of Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

This armor was made for Emmanuel Philibert when he was about eighteen years old for tournament on horseback and on foot. The unknown Milanese armorer signed his works with a tiny castle on the neck of the breastplate. All parts of Emmanual Philibert’s armor are decorated with a repeating pattern of lozenges containing military trophies and palm leaves passing through a crown. Only traces remain of the original gilt finish of these motifs, which stood out against a darkened background that has also worn away.

Master of the Castle, Italian, documented 1590–1620, Armor of Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy, Milan, c. 1606, etched and gilt steel, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

Philip II's daughter Isabella Clara Eugenia, governor of the Spanish Netherlands, sent several sets of opulent armor as a gift to her nephew, Philip IV. For this portrait of the king, Gaspar de Crayer combined features of two different garnitures for artistic effect. He copied the type of armor from one set, but borrowed its decoration of gilded foliage from another.

Gaspar de Crayer, Flemish, 1584–1669, Philip IV with Two Servants, between 1627 and 1632, oil on canvas, Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores y de Cooperación, Madrid