South India: Madura and Tanjore

Madura: The Vygay River, with Causeway, across to Madura, January–February 1858

National Gallery of Art, Washington, The Carolyn Brody Fund and Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation through Robert and Joyce Menschel, 2006.6.1

For Hindus, a sacred site is a tirtha, literally a ford or crossing place that allows one to pass from worldly engagement to transcendence. In Tripe’s photograph the dramatically receding causeway leads the eye to the gateway around the Minakshi Sundareshvara Temple, dedicated to the god Shiva and his consort Minakshi. Shiva is said to have created the Vygay River, which, like most rivers in the far south of India, dries up during the hottest months of the year.

Madura: Pillars in the Recessed Portico in the Roya Gopurum, with the Base of One of the Four Sculpted Monoliths

January–February 1858

The British Library, London

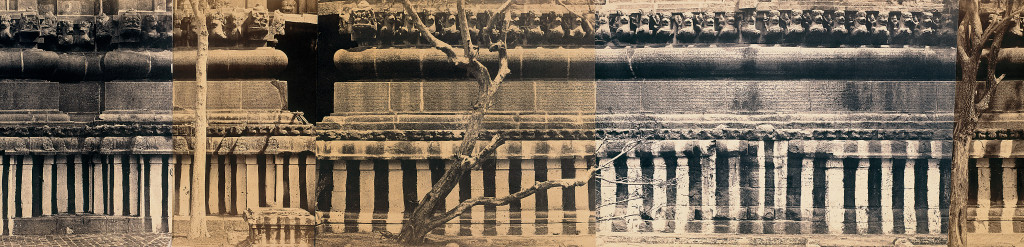

Madura: West Front of the Roya Gopurum, January–February 1858

The British Library, London

The enormous base for this unfinished gopuram, or gateway, was said to be 57 feet high and deeply buried in the ground.

Madura: The Blackburn Testimonial, January–February 1858

The British Library, London

The column in this photograph was named after John Blackburn, who oversaw the transformation of Madura in the 1840s. He ordered old stone fortifications to be torn down and a new network of streets to be constructed. In the background Tripe also captured the domes, high roofs, and a row of free standing columns from the great palace of Trimul Naik, whose family had ruled this area of south India for hundreds of years until they were defeated by the British in 1736.

Madura: The Great Pagoda, West Gopurum, January–February 1858

The British Library, London

This photograph posed a technical challenge for Tripe. Without a specialized camera and a very good lens, photographers could rarely get close enough to capture an entire building and simultaneously reveal its design and ornamentation. Tilting the camera upward to include the apex of a building introduced unnatural converging lines. Tripe corrected this problem by using a newly invented feature called a rising-front that enabled him to keep the back of his camera absolutely horizontal while raising the lens vertically to capture the top of the building.

Madura: The Great Pagoda, Inside View of Gateway of East Gopurum with Veeravasuntharoya’s Munduppum in Front,

January–February 1858

The British Library, London

Madura: Trimul Naik’s Choultry, Side Veranda from West, January–February 1858

The British Library, London

Although earlier visitors had surveyed Trimul Naik’s Choultry (a resting place for travelers), Tripe was the first person to create a thorough photographic record of the building, with 20 large photographs and 18 smaller ones. This picture of the southern aisle of the 300-foot-long columned chamber emphasized its massive scale.

Madura: Trimul Naik’s Choultry, Center Nave from West End, January–February 1858

The British Library, London

Madura: The Great Pagoda, Interior View of Part of Muroothappa Sarvacar Munduppum, January–February 1858

Wilson Centre for Photography, London

Trimium: Fort, Interior Hold, with the Main Street, Taken from the Top of the Gateway, February 1858

The British Library, London

The British fort at Trimium was a reminder of past military campaigns in the region and the establishment of British rule over south India. But Trimium was important to local Hindus because of nearby temples to Shiva and Vishnu.

Poodoocottah: Durbar, February–March 1858

The British Library, London

This picture of a formal court ceremony shows Ramachandra Tondaiman (reigned 1839–1886), raja of the princely state of Poodoocottah, enthroned beneath an elaborate canopy. Seated on European chairs are his principal nobles, including the British-appointed prime minister of Poodoocottah. Tripe thus captured the changed political world of the princely rulers in colonial India, who had acquired a taste for European amenities — furniture, gas lighting, and chandeliers — while seeing their power increasingly circumscribed.

Madura: The Great Pagoda Jewels, January–February 1858

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, Cynthia Hazen Polsky Gift, 2005

Much of the finest jewelery of south India was intended as ornamentation for the gods, who were considered sovereigns; mortal kings ruled on their behalf. Despite the protestations of the native manager, Tripe gained privileged access to these temple jewels, generally inaccessible to Europeans, perhaps through the authority of the local agent of the East India Company. He photographed this subject and several others (see slides 8, 11, 13, and 14) using collodion glass negatives, most likely because he was working indoors with little light where the faster collodion process was advantageous.

Elliot Marbles and Other Sculpture from the Central Museum Madras: Group 26, May–June 1858

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Rubel Collection, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace and Richard and Ronay Menschel Gifts, 1997

In 1853 the newly founded Government Central Museum Madras acquired a collection of notable marble sculptures that the Scottish orientalist Walter Elliot had excavated from the Buddhist stupa at Amaravati in south India in 1845. A contemporary referred to them as the “Elliot marbles,” linking them to the recently discovered “Elgin marbles” from ancient Greece. Tripe photographed them where they had been left outside in a haphazard arrangement on the grounds of the museum, their display showing no understanding of their original location or arrangement.

Central Museum Madras: Group 27, May–June 1858

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Cynthia Hazen Polsky Gift and The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1991

Tanjore: Great Pagoda, Figure Sculpted on the Side of the Inner Gopurum, March–April 1858

The British Library, London

Prints by early travelers brought the Brihadishvara Temple, known as the Great Pagoda at Tanjore, to the attention of Europeans, many of whom considered it to be the most splendid temple in India. Tripe’s pictures, such as this one featuring a finely carved, four-armed guardian figure, were the first photographs to confirm the grandeur of the structure.

Tanjore: Great Pagoda, Entrance Looking Outwards, March–April 1858

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 1995.36.120

The temple, with its deeply molded base, is built on a high platform and painted with vertical red and white stripes. These stripes, a standard element in south Indian temple wall decoration, are sometimes thought to represent the dual nature of existence: male and female, Shiva and Shakti, God and man. The temple’s base is also covered with inscriptions which Tripe photographed in a groundbreaking panorama (see the following two slides).

Installation view of Tripe's panoramic scroll, Tanjore: Great Pagoda, Inscriptions around Bimanum, displaying approximately 4 of the 21 exposures

Tanjore: Great Pagoda, Inscriptions around Bimanum (detail), March–April 1858

Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal, Acquired with the assistance of a grant approved by the Minister of Canadian Heritage under the terms of the Cultural Property Export and Import Act

Tanjore: Wrought-Iron Gun on a Cavalier in the Fort, March–April 1858

The British Library, London

This “monster gun of Tanjore,” which dates to the mid-17th century, was more than 24 feet long and 10 feet in circumference. It was said to have been fired only once causing a sound that seemed, a missionary wrote, as “if mount Meru had exploded.”