Verrocchio, Connoisseurship, and the Photographs of Clarence Kennedy

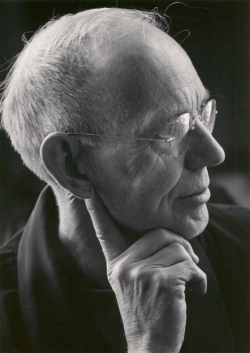

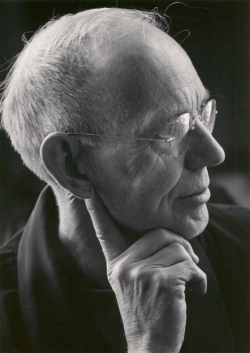

Ansel Adams, Clarence Kennedy, 1955, gelatin silver print, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Clarence Kennedy (1892–1972), an art historian at Smith College and self-proclaimed “scholar-photographer,” revolutionized documentary art photography with subtle and illuminating details of Italian Renaissance sculpture. The limited photographic resources available for teaching art history in the early 1920s led Kennedy to pursue photography, eventually resulting in his photographic series Studies in the History and Criticism of Sculpture. Sculptors with large workshops, such as Andrea del Verrocchio (c. 1435–1488) and Desiderio da Settignano (c. 1429–1464), particularly inspired him. His exquisitely detailed photographs allowed him to compare motifs, methods, and styles to propose distinctions between the master’s hand and the work of his assistants.

Kennedy was highly regarded by both art historians and photographers. Among his closest friends were Polaroid founder Edwin Land (1909–1991) and Ansel Adams (1902–1984). Adams described Kennedy’s photos as revealing “not only his perception of the varied subjects, but his extraordinary ability to record the glow of marble and the sheen of bronze in breathtakingly beautiful prints.”

Photographing marble sculpture in situ requires a light source bright enough to illuminate the sculptures without obliterating the details and producing dark shadows. Kennedy solved this problem with his “pencil of light” method, where a bright light source was moved continuously over the object during a long exposure. He would leave the shutter of the camera open for a longer period than necessary, adding anywhere from minutes to hours to his process to allow his camera to capture the shifting light. This method would introduce desirable reflections and soften edges in order to mimic diffused daylight, resulting in what he called a “thick negative,” rich and full of detail.

The Monument to Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri

Volume seven of Kennedy’s Studies was entitled The Unfinished Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio to the Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri at Pistoia where his roughly 6x10-inch photographs are accompanied by text written by his student, Elizabeth Wilder (1907–1989). It includes thirty-two full-page details and nine small, contextual overall photographs tipped into the text. Kennedy photographed the monument from 1930 to early 1931.

Clarence Kennedy, Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print

This roughly 3x5” image tipped into the text is the only full view of the monument included in the Forteguerri album. Kennedy was seldom interested in overall views and often excluded them altogether, assuming they could be found elsewhere.

The Forteguerri cenotaph is nearly three stories high, with life-size figures including Christ surrounded by four angels with the virtues of Faith, Hope, and Charity positioned above putti and a bust of the cardinal. Verrocchio received the commission in 1476 but left it incomplete in the hands of his workshop assistants when he moved to Venice in 1486. The monument’s precise location in the Cathedral of Pistoia was not decided until after Verrocchio’s death, and its initial installation was significantly altered in the 16th and 18th centuries. Charity, the bust, and the flanking putti are all later additions. These modifications, as well as the monument’s placement high on the wall in a dark aisle had made it nearly impossible to study the sculpture properly before Kennedy’s campaign. His photographs focused new attention on a major work long dismissed as a shop production. They allowed Kennedy, Wilder, and subsequent scholars to better study and compare the details within this monument and throughout Verrocchio’s oeuvre in order to distinguish the hand of the master from the work of his assistants.

Christ the Redeemer

The Forteguerri figure of Christ is the most finished on the monument and one of the few consistently considered to be by Verrocchio. Kennedy’s details of Christ’s face, hands, feet, and drapery reveal a sensitivity typical of Verrocchio’s carving. The photos also capture the beauty of the undulations of the cloak while still suggesting the form underneath.

The head of the cherub at Christ’s feet is also considered to be by Verrocchio. Chisel marks in the ears and eyes indicate a slightly less finished state. The images of the cherub at the end of the following group convey the cramped composition of the monument, a result of the damaging reinstallation by Gaetano Masoni in 1753–1754.

Clarence Kennedy, Beheading of Saint John the Baptist by Andrea del Verrocchio, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence, 1932, gelatin silver print

Clarence Kennedy, Christ as the Redeemer: Head, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Christ as the Redeemer: Left Hand, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Christ as the Redeemer: Drapery between the Knees, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Christ as the Redeemer: Right Foot with Drapery Drawn across the Ankle, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio, Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

Clarence Kennedy, Christ as the Redeemer: Left Foot Resting on Wing of Cherub, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Christ as the Redeemer: Head of Cherub, from the Side, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

The Virtues of Faith and Hope

After the figure of Christ, Verrocchio’s hand, or direct influence, is most prevalent in the draperies of the personifications of the virtues of Faith and Hope, hovering in the bottom half of the monument.

Faith’s dramatic but not overly ornamental drapery evokes volume and movement. Kennedy carefully lit the intricately carved marble to highlight the dramatic composition of the folds that echo Christ’s, above. Her head is unfinished, but the subtleties of her mouth and eyebrows, as well as a perceived understanding of her bone structure, convinced Wilder that her face was by Verrocchio.

Clarence Kennedy, Faith, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Faith: Head, Not Quite in Profile to the Right, as Seen from in Front, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Faith: Drapery behind the Right Thigh, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio, Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

Clarence Kennedy, Faith: Drapery below the Waist and over the Left Thigh, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Faith: Left Hand, with the Drapery over the Arm, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Faith: Right Leg and Foot, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

In general Hope’s drapery is an exaggerated interpretation of Verrocchio’s more restrained style. Sections of the voluminous drapery below her waist, however, are less ornate and much closer to the hand of the master. The vapid look on her puffy face, as well as the formulaic treatment of her hair, bodice, and wings, have led her to be ascribed to Verrocchio’s workshop.

Clarence Kennedy, Hope, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Hope: Head, Facing nearly Left, as Seen from in Front, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio, Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

Clarence Kennedy, Hope: Head, in Profile to the Left, as Seen from the Right, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Hope: Hair, Veil and Wing, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Hope: Drapery below the Waist, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio, Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

Clarence Kennedy, Hope: Fold of Drapery Falling between the Legs, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Hope: Drapery Floating behind the Left Leg, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

The Angels

The four angels surrounding Christ are all inferior to the other Verrocchio-era figures on the monument. They have particularly suffered from the eighteenth-century reinstallation where elements, such as their wings, were cut in order to fit the figures into the imposed frame.

The angel at the lower left is highly finished and characterized by Wilder as the most successful copy of Verrocchio’s models. The surfaces of the face are smooth, and the subtleties of form fully realized. The contours of shadow in the brows and under the lip are particularly appealing. Verrocchio’s hand may be seen in the complicated folds of drapery as well as the beautifully intricate and organic wings on this angel where Kennedy’s careful lighting reveals the delicate layers of built-up relief. Elements such as the awkward and impossible position of the angel’s hands, however, must have been the work of an inferior sculptor.

Clarence Kennedy, Lower Angel to Observer’s Left, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Lower Angel to Observer’s Left: Head, Facing Slightly Right, as Seen from in Front, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Lower Angel to Observer’s Left: Drapery below the Waist, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio, Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

Clarence Kennedy, Lower Angel to Observer’s Left: Right Wing, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Lower Angel to Observer’s Left: Drapery over the Hips, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Lower Angel to Observer’s Left: Fold of drapery between the Legs, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Lower Angel to Observer’s Left: Hand and Arms, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

The angel at the upper left is particularly awkward and weak. It is the least finished figure on the monument, perhaps because of the limited visibility due to its high placement. The presence of Christ’s blessing hand so close to her face is a result of Masoni’s changes. This angel’s ineffectiveness is made particularly clear by the unimaginative folds, feathers, and ropey locks of hair.

Clarence Kennedy, Upper Angel to Observer’s Left, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Upper Angel to Observer’s Left: Head, Looking to the Right, as Seen from in Front, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Upper Angel to Observer’s Left: Right Wing, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Upper Angel to Observer’s Left: Right Hand, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Upper Angel to Observer’s Left: Right Foot, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

The exaggerated interpretation of Verrocchio’s designs as seen in the figure of Hope is also present in the lower right angel. The folds are linear and overly erratic, creating a mass of forms unrelated to the shapes or movement of the figure. The simplistic treatment of the upper bodice is also indicative of a less skilled artist. His attempt to imply the forms under the drape is too aggressive, lacking Verrocchio’s grace. Chisel marks can still be seen on this angel’s face, but the hair is highly finished. Such varied degrees of finish in the same figure may suggest that different sculptors were responsible for particular elements of each figure, such as hair or drapery. The broken foot is another casulty of the reinstallation.

Clarence Kennedy, Lower Angel to Observer’s Right, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Lower Angel to Observer’s Right: Head, Facing Slightly Right as Seen from the Left, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Lower Angel to Observer’s Right: Figure to the Waist, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Lower Angel to Observer’s Right: Drapery below the Waist, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio, Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

Clarence Kennedy, Lower Angel to Observer’s Right: Right Hand, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Lower Angel to Observer’s Right: Fold of Drapery Floating behind the Left Leg, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Lower Angel to Observer’s Right: Left Foot with the Drapery above the Ankle, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Unlike the other angels, the upper right angel seems to have been executed by a single sculptor. The marble carving is highly finished, but the resulting figure is quite flat and without the suggestion of bone or muscle. The folds of the drapery are nearly parallel, lacking the visual complexity of the other Forteguerri figures.

Clarence Kennedy, Upper Angel to the Observer’s Right, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Upper Angel to the Observer’s Right: Head, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Upper Angel to the Observer’s Right: Drapery below the Waist, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Upper Angel to the Observer’s Right: Left Foot, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

The Inscription Panel

While inconsistencies of style and ability throughout the monument make it indisputable that Verrocchio’s workshop participated, the only identifiable collaborator generally agreed upon is Verrocchio’s probable assistant, Francesco di Simone Ferrucci (1437–1493), for the putti at the base of the monument.

Clarence Kennedy, Inscribed Slab: Two Putti Upholding the Inscription, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Inscribed Slab: Head of the Putto to Observer’s Right, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Inscribed Slab: Legs and Feet of the Putto to Observer’s Right, 1930/1931, gelatin silver print, detail of Cardinal Niccolò Forteguerri Monument by Andrea del Verrocchio, Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

The chubby putti from the inscription panel resemble a marble figure acquired by the De Young Art Museum in 1949 as by Verrocchio. Kennedy photographed it while collaborating with the curator Walter Heil (1929–1973) on its attribution. It is now attributed to Francesco di Simone Ferrucci. There are many parallels between the treatment of the De Young and Forteguerri putti’s playful feet, round stubby fingers, heavily lidded eyes, slightly open smallish mouths, and folds of fat.

Ansel Adams and Edwin Land planned an unrealized monograph on Kennedy for which Adams printed Kennedy’s negatives, including a detail of this putto. Adams expressed difficulty in capturing the original tone, values, and feeling of Kennedy’s prints.

Clarence Kennedy, Putto by Francesco di Simone Ferrucci, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, c. 1949, gelatin silver print

Clarence Kennedy negative printed by Ansel Adams, Putto by Francesco di Simone Ferrucci, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, c. 1965, gelatin silver print. Reproduced with permission from the Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. All Rights reserved

Commissions from Sir Joseph Duveen

Clarence Kennedy, Putto Poised on a Globe by Andrea del Verrocchio, National Gallery of Art, 1930, gelatin silver print

In 1930 Kennedy was summoned to Paris by his intermittent employer, the art dealer Sir Joseph Duveen, to take photographs of his newly purchased Gustave Dreyfus collection, including this unbaked clay putto by Verrocchio. It was later purchased by Andrew Mellon (1855–1937) for the National Gallery of Art.

Elements of the putto are closely related to Verrocchio’s Putto with a Dolphin in the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, as well as the Forteguerri cherub. The rounded cheeks, hooded eyes, broad forehead, and folds of flesh are all extremely similar.

Kennedy’s photos of three-dimensional works walk the viewer around the sculpture, allowing one to appreciate it from different angles and explore it more fully.

Clarence Kennedy, Putto Poised on a Globe: Back by Andrea del Verrocchio, National Gallery of Art 1930, gelatin silver print

Clarence Kennedy, Putto Poised on a Globe: detail by Andrea del Verrocchio, National Gallery of Art, 1930, gelatin silver print

Clarence Kennedy, Putto Poised on a Globe: detail by Andrea del Verrocchio, National Gallery of Art, 1930, gelatin silver print

Clarence Kennedy, Giuliano de’ Medici by Andrea del Verrocchio, National Gallery of Art, 1930, gelatin silver print

In addition to the National Gallery’s Putto, Kennedy photographed this bust of Giuliano de’ Medici for Joseph Duveen for his catalog on the Dreyfus Collection. Like the Putto, this bust was eventually purchased by Mellon for the Gallery.

Kennedy described this profile view as “the longest exposure I have ever made. Made on slow panchromatic film, I opened the shutter at 5 o’clock of a summer day and shut it again at 8 the next morning.” The rising and setting sun served as Kennedy’s “pencil of light.” His long exposure allowed him to capture the many layers of detail as his light source glanced off the dark, glossy nineteenth-century coating that has since been removed.

Clarence Kennedy, Giuliano de’ Medici: Three-quarter View by Andrea del Verrocchio, National Gallery of Art, 1930, gelatin silver print

Clarence Kennedy, Giuliano de’ Medici: Profile View by Andrea del Verrocchio, National Gallery of Art, 1930, gelatin silver print

Clarence Kennedy, Giuliano de’ Medici: Breastplate by Andrea del Verrocchio, National Gallery of Art, 1930, gelatin silver print

Clarence Kennedy, Bust of a Young Woman by Andrea del Verrocchio, The Frick Collection, 1930, gelatin silver print

This bust, now in the Frick Collection, was also among the Dreyfus sculptures purchased by Duveen; this one was sold to John D. Rockefeller (1839–1937).

Kennedy captures the Frick bust’s elegant serenity with his choice of viewpoint and subtle lighting which models her face, enhancing the beauty of the portrait. Some critics, in fact, have accused Kennedy of making objects seem more beautiful than they actually are. He vehemently disagreed, saying he only revealed what was already there.

The geometric simplicity of the detail of her bodice displays Kennedy’s virtuosity in capturing low relief and choosing details. Such artful and aesthetically pleasing images catapulted him above the role of documentary photographer to that of artist.

Clarence Kennedy, Bust of a Young Woman: Three-quarter View from Right by Andrea del Verrocchio, The Frick Collection, 1930, gelatin silver print

Clarence Kennedy, Bust of a Young Woman: Three-quarter View from Left by Andrea del Verrocchio, The Frick Collection, 1930, gelatin silver print

Clarence Kennedy, Bust of a Young Woman: Bodice by Andrea del Verrocchio, The Frick Collection, 1930, gelatin silver print

The Silver Altar of San Giovanni

Clarence Kennedy, Beheading of Saint John the Baptist by Andrea del Verrocchio, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence, 1932, gelatin silver print

Kennedy’s interest in Verrocchio continued with his campaign to photograph the Silver Altar from the Baptistery of Florence decorated with scenes from the life of Saint John the Baptist. The figures in this panel were cast individually and can be completely removed from the background, resulting in complex levels of relief. Kennedy manipulated his light source to balance these varying surfaces, the resulting shadows, and the highlights of the silver.

Despite their different media, the Forteguerri Christ and the Silver Altar Saint John the Baptist have many similarities, especially in the sinuous locks of hair, sharply defined cheekbones, and deep drapery folds. Both figures have a powerful presence and exude an inner strength. The sweet face of the soldier, far left, loosely resembles the monument’s angels.

Clarence Kennedy, Soldiers and St. John, Florence, 1932, gelatin silver print, detail of The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist by Andrea del Verrocchio, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence

Clarence Kennedy, St. John the Baptist, 1932, gelatin silver print, detail of The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist by Andrea del Verrocchio, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence

Clarence Kennedy, Soldier, 1932, gelatin silver print, detail of The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist by Andrea del Verrocchio, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence

Clarence Kennedy, Soldier, 1932, gelatin silver print, detail of Beheading of Saint John the Baptist by Andrea del Verrocchio, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence, National Gallery of Art Library, department of image collections

Clarence Kennedy, Soldier, 1932, gelatin silver print, detail of Beheading of Saint John the Baptist by Andrea del Verrocchio

Clarence Kennedy, Executioner, 1932, gelatin silver print, detail of The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist by Andrea del Verrocchio, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence

In addition to complementing the exhibition Verrocchio: Sculptor and Painter of Renaissance Florence, this feature corresponds with an “In the Library” installation on view in the Library atrium, September 16, 2019, to January 10, 2020. The Gallery would like to thank the Harvard Fine Arts Library, the repository of Kennedy’s negatives and professional papers, for the loan of plates from their unbound, deluxe edition of the Forteguerri monograph. The Gallery’s department of image collection’s bound copy is among its extensive Kennedy holdings, including a unique unpublished portfolio entitled The Quattrocento Panels of the Silver Altar of San Giovanni, comprised of several reliefs now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence. Harvard’s Forteguerri plates are displayed alongside other Kennedy photographs from the Gallery’s collection, including Verrrocchio’s Silver Altar relief and sculptures from the Gustave Dreyfus Collection photographed for the art dealer Joseph Duveen. The juxtaposition of these images illustrates Kennedy’s role as connoisseur, thoughtful art historian, and innovative photographer.

All photographs in this feature are from the holdings of the Library's department of image collections, unless otherwise noted.