During the turbulent decades following World War II, architects and engineers were engaged in extensive new construction and developing common standards of living. To confront the scale of the global building crisis, multidisciplinary collectives of itinerant, for-hire, technical experts were founded, as exemplified by the Atelier des Bâtisseurs (more commonly referred to as ATBAT). In response to the exigencies of European reconstruction and decolonization abroad, ATBAT proposed “habitat for the greatest number” as a universal framework of building for the common man. Moving beyond the basic demands of “shelter” prescribed by the nascent United Nations and designed to be more comprehensive than the “habitation” promulgated by the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne, ATBAT’s holistic habitat aimed to satisfy both spatial and spiritual needs, and to evolve in accordance with its users.

Dedicated to case studies of collective housing in Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Arctic, my dissertation charts ATBAT’s approach to building habitat in diverse cultural and climatic environments in the service of welfare states, colonial regimes, and newly independent nations. My research traces the movement of ATBAT personnel, designs, and ideas, revealing the networks and logics of exchange facilitated by these interactions. It also challenges claims of architectural modernism’s “Esperanto,” with assumed applicability in all contexts and climes. As a result, the selected projects illustrate ATBAT’s development of habitat both as theoretical construct and as realized in construction, while often exposing the distance between the two. The dissertation is therefore as much a study of architectural form as of architectural language, evaluating criticism, treatises, exhibitions, and patents in relationship to the built domain.

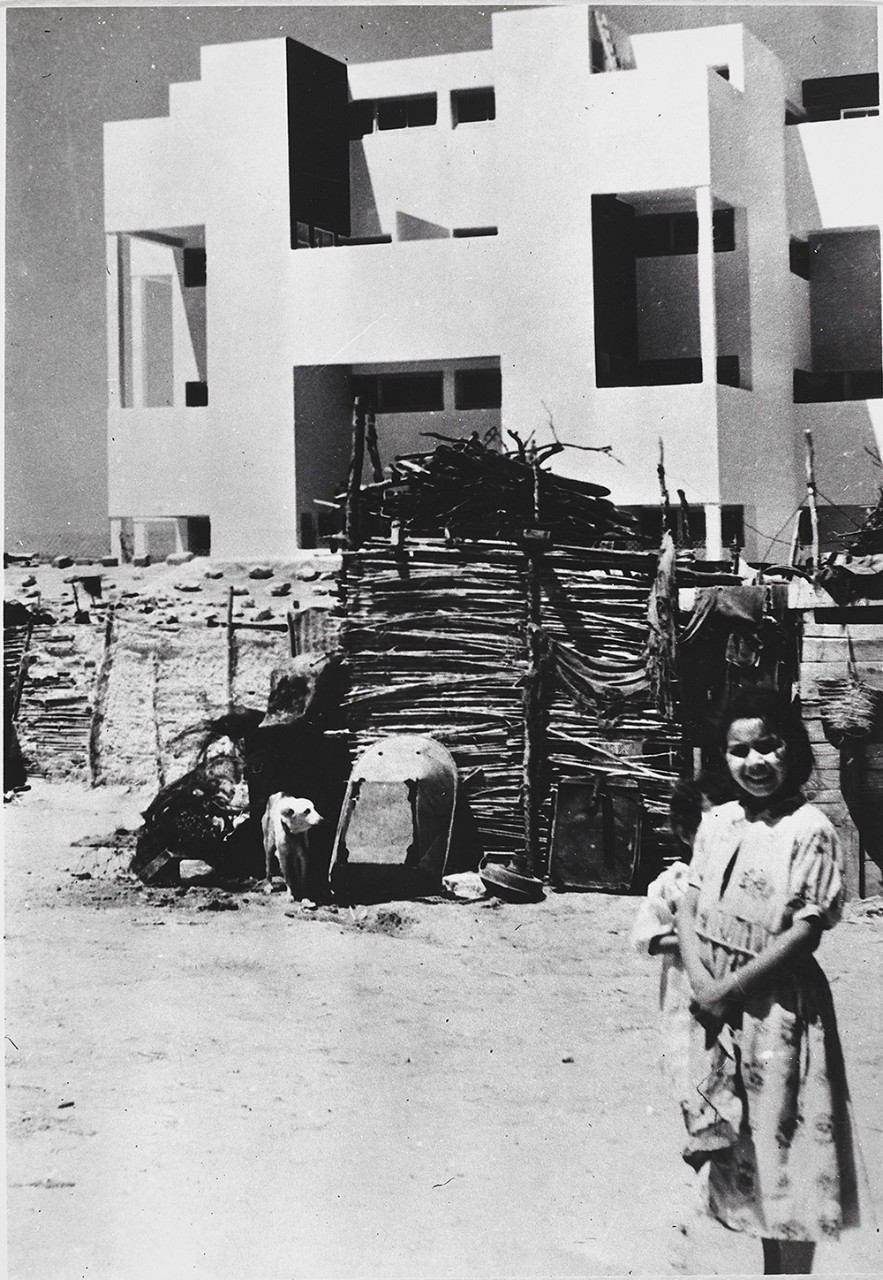

The first chapter addresses the work of an affiliate office, ATBAT-Afrique, in the colony of Algeria and the protectorate of Morocco shortly before each territory achieved independence. In commissions for distinct ethnic-religious populations possessing differing dwelling cultures and legal statuses, ATBAT-Afrique’s work highlights the limitations of habitat’s emancipatory potential, as well as the contradictions that arise from applying international standards while attending to local conditions. By reading across colonial territories (rather than in relation to the metropole), these examples explore the shifting aesthetic valences and political motivations undergirding mid-century architectural discourse, particularly ideas concerning the “modern” and “vernacular.”

The second chapter investigates notions of comfort—both physical and psychological—as illustrated by worker housing in two settings: a scientific research station in Arctic Greenland and a bauxite mine in tropical Guinea. In these climatic extremes, habitat’s ability to accommodate body and spirit was tested, as well as reflected in hierarchical conceptions of manual and intellectual labor. Similarly, via analyses of the two projects’ broader ecological and economic associations, shared building technologies and practices of resource extraction serve to complicate modernist divisions between craft and prefabrication.

The third chapter examines constructions of identity through strikingly similar housing estates in the capitals of postwar France and postcolonial Cambodia. In each, the role of state-sponsored domestic architecture to shape model citizens—and to operate as an instrument of biopower—is questioned. Additionally, foregrounding the design chronology of the Phnom Penh example disrupts established narratives of architectural influence. This pairing thus reframes the Western paradigm of center versus periphery while pointing to the inescapably sited nature of “universalism” and the corollary invention of regionalism.

Taken together, these chapters reveal the paradoxes and animating tensions of postwar architectural practice and, by extension, problematize the structuring binaries of the period’s discourse and historiography. Although my dissertation adopts a monographic focus, its purpose is not to signal ATBAT’s singularity, but rather to mobilize its oeuvre in order to perform a critique of architectural modernism from within. By addressing dominant social, economic, and political themes through postcolonial, ecological, and post-structural lenses, I attempt to provide a more complex and, at times, conflicted account of global building practices and production as engaged with reconstruction and decolonization.

In the first year of my fellowship, I traveled to Algeria, France, Morocco, Switzerland, and the United States to consult archival materials and perform site visits. During the second year, in residence, the Center’s scholarly community invaluably shaped and contributed to the completion of my dissertation. I am grateful for the opportunity to have learned from the diverse cohort of fellows and benefited from their collegial support.

[New York University]

Twenty-Four-Month Chester Dale Fellow, 2019–2021

Johanna Sluiter will return to the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University to complete her dissertation.