Gregorio Comanini’s Counter-Reformation treatise The Figino, or, On the Purpose of Painting (1591) makes an intriguing declaration about the nature of painting: paintings are imitations, and they are games. The Mantuan writer continues on the theme of

“The Art of Play” is organized in four chapters, arranged around spaces of play. From chapter to

To set the stage, chapter 1, “The Grid as Symbolic Form: From Chess to Linear Perspective,” focuses on the paradigm of the grid and on the gridded chessboard’s resonance with urban and pictorial space. By examining the analogy of the game of chess as society and how chess represented mastery over intellectual systems, this chapter considers the relationship between chess and pictorial representation, positing the artist as master of the system of linear perspective and the painting as game (like the chessboard), mediating interactions between the artist and viewer through the system of the grid and the dialogic format of both the game and the painting.

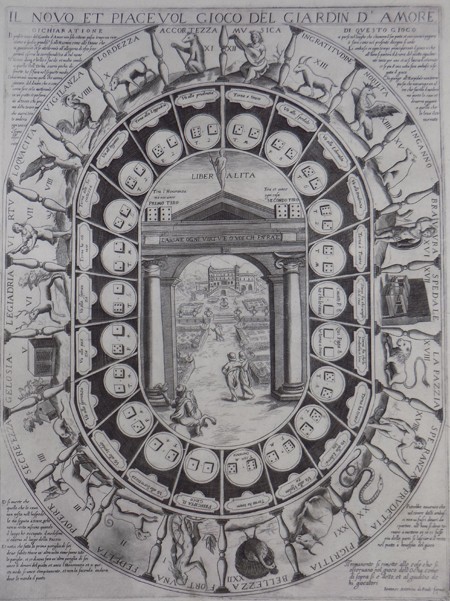

Chapter 2, “Pathways of Play: Printed Game Boards in Counter-Reformation Italy,” considers the material culture of play in the salon in the form of printed game boards and the network of agency among artist, print, and player in the home. Printed table games in the style of the “game of the goose” became immensely popular by the end of the sixteenth century, not merely serving as entertainment but also mapping and

Moving outward into the spaces in which games were played, chapter 3, “Performing Pictures: Parlor Games and Visual Engagement in the Cinquecento,” examines how the play and performance of parlor games in mid-sixteenth-century aristocratic salons invoked and created models for sensory, and in particular visual, engagement. This chapter contributes to the central thesis of the dissertation—that

Chapter 4, “Power over the Piazza: Civic Ritual and Quotidian Play,” considers the significance and evolution of a century of public games in the urban space of Florence, from the foundation of the duchy in 1530 to the plague of 1630 and the rapid economic decline that followed. Public games sanctioned by the Medici government as well as transitory activities of play in the communal street forged competing jurisdictions over urban space. Transgressive quotidian games had a direct impact on the city’s socially invested topography, thereby contributing to Florentine identity within, between, and beyond factions.