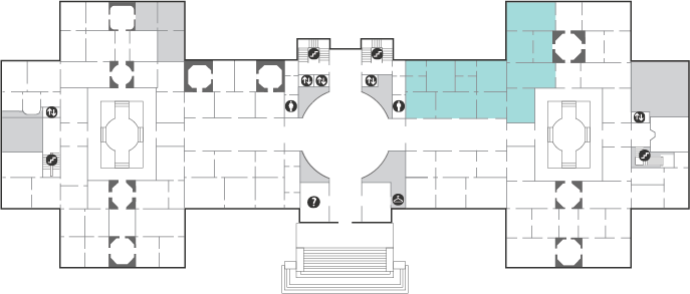

West Building Audio Tour: French Impressionist Paintings, 19th Century

Use your smartphone to explore a wide range of works through the voices of National Gallery of Art curators. Set your own pace by listening to as many stops as you like in the order you choose.

To listen to information about a work of art, enter the stop number in the box below, select go, and press the play button when the stop appears. Please be mindful of other visitors and use headphones while listening to the audio tour.

| French Impressionist Paintings, 19th Century | American and European Paintings, 18th–20th Centuries |

| Italian Renaissance Paintings, 13th–16th Centuries | Dutch and European Paintings, 15th–18th Centuries |

Stop not found

Please try a different number.

Stop 165

Claude Monet, The Japanese Footbridge, 1899 - The Japanese Footbridge

-

This painting is part of a 12-canvas series that Claude Monet made during the summer of 1899. All the paintings feature the Japanese-style wooden footbridge that spanned a water lily basin—the centerpiece of the water garden Monet created at his home in Giverny—as viewed from the western bank of the pond. The 12 paintings are firmly rooted in japonisme, the then-contemporary vogue for all things Asian. Monet himself was an avid admirer of Japanese prints, which he collected throughout his life and displayed prominently in his home.

We are working to transcribe this audio.

Stop 182

Auguste Renoir, A Girl with a Watering Can, 1876 - A Girl with a Watering Can

-

Auguste Renoir’s colors reflect the freshness and radiance of the impressionist palette, while his handling is more controlled and regular than in his landscapes, with even brushstrokes applied in delicate touches, especially in the girl’s face. Brilliant prismatic hues envelop the child in an atmosphere of warm light and charmingly convey her innocent appeal. A similarly depicted child appears in other paintings by Renoir, suggesting she was a favorite figure whom the artist knew from real life.

We are working to transcribe this audio.

Stop 210

Edouard Manet, The Old Musician, 1862 - The Old Musician

-

The Old Musician features a motley group of the urban poor of Paris: a ragpicker wearing a battered top hat, a turbaned man, three children, one of whom carries a baby, and a wandering musician. These characters are set against an undefined background that has been identified as a slum on the edge of Paris known as Little Poland. Édouard Manet’s choice to depict on such a grand scale the people who had been uprooted by the modernization of Paris under Baron Haussmann seems to introduce an element of social commentary. Yet the lack of interaction among the figures and the ambiguity of the setting deprive the painting of a conventional narrative, rendering its ultimate meaning opaque.

We are working to transcribe this audio.

Stop 211

Georges Seurat, The Lighthouse at Honfleur, 1886 - The Lighthouse at Honfleur

-

The Lighthouse at Honfleur was conceived using Georges Seurat’s daring divisionist technique. This process entailed applying dabs of pure color on a canvas in order for the colors to mix optically when viewed from a distance. Drawing upon small preparatory studies made on panel outdoors, Seurat re-created the composition on a canvas in his Paris studio, where he then refined the technique by methodically applying smaller dots of pigment that represented a broader spectrum of colors.

We are working to transcribe this audio.

Stop 218

Mary Cassatt, The Boating Party, 1893/1894 - The Boating Party

-

In the winter of 1893–1894, Mary Cassatt traveled with her mother to Cap d’Antibes, a peninsula on the French Mediterranean coast. Inspired by the light and color of the local landscape, Cassatt painted this work. With its sharply cropped forms, tilted picture plane, and bird’s-eye perspective, the painting’s debt to Japanese woodblock prints—which Cassatt admired and collected—is undeniable. However, the flattened forms and harsh, acidic color palette are equally a response to the dazzling sun of the south, known to bathe everything in strong, even light. The boldly geometric quality of this composition seems at odds with its subject, resulting in a work of surprising intensity.

We are working to transcribe this audio.

Stop 179

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Apples and Peaches, c. 1905 - Still Life with Apples and Peaches

-

In a still life, each object, each placement, and each viewpoint represent a decision by the artist. Paul Cézanne painted the objects pictured here many times. The table, patterned cloth, and flowered pitcher were all props he kept in his studio. Here, the table tilts unexpectedly, defying traditional rules of perspective. Similarly, we see the pitcher in profile but are also allowed to look down into it. Over the course of days, he would move his easel, painting different objects—or even the same one—from different points of view. Each time, he painted what he saw. It was his absorption in the process of painting that pushed his work toward abstraction.

We are working to transcribe this audio.

Stop 170

Paul Cézanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat, 1888-1890 - Boy in a Red Waistcoat

-

Depicting an Italian boy named Michelangelo di Rosa, this work is one of four devoted to this model that Paul Cézanne produced from 1888 to 1890. In each painting, the young man wears the same striking red vest, which introduces a bold accent into each of the otherwise muted compositions. While the loose brushwork and lack of shading give the work a modern appearance, the boy’s pensive demeanor and elegant pose—his weight shifted onto one leg with hips tilted, and one arm bent with hand resting on his waist—evoke Italian Renaissance portraits by artists whom Cézanne admired, lending a consciously timeless quality.

We are working to transcribe this audio.

Stop 229

Edgar Degas, Four Dancers, c. 1899 - Four Dancers

-

Four Dancers represents the culmination of Edgar Degas’s lifelong fascination with the ballet. His largest, and arguably his last, great painting of the subject, it depicts four dancers adjusting their costumes before going on stage. For this composition, Degas drew upon numerous studies—produced in chalk, pastel, and even photography—of dancers in similar poses. It has been suggested that rather than depicting four different figures, Degas may have portrayed a single dancer as she moves through space, changing position and gesture as she goes. The overall palette of greens and fiery orange lends a dreamlike quality to the subject.

We are working to transcribe this audio.

Stop 195

Paul Gauguin, Self-Portrait, 1889 - Self-Portrait

-

This self-portrait, painted on a cupboard door from the dining room of an inn in the Breton hamlet Le Pouldu, France, is one of Paul Gauguin’s most important and radical paintings. His haloed head and disembodied right hand, a snake inserted between the fingers, float on amorphous zones of yellow and red. Elements of caricature add an ironic and aggressively ambivalent inflection. Gauguin’s friends called it an unkind character sketch.

We are working to transcribe this audio.

Stop 238

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Marcelle Lender Dancing the Bolero in "Chilpéric", 1895-1896 - Marcelle Lender Dancing the Bolero in "Chilpéric"

-

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec had a passion for theater in all its forms, and among his favorite subjects was the redheaded actress Marcelle Lender. During a three-month run of the operetta Chilpéric, he attended the show more than 20 times, arriving just to see Lender dance the bolero in the second act. He ultimately produced six lithographs and two paintings inspired by her appearance in Chilpéric, including this monumental canvas. Toulouse-Lautrec’s admiration was not reciprocated. “What a horrible man!” Lender is said to have remarked. “He is very fond of me. . . . But as for the portrait you can have it!”

We are working to transcribe this audio.