Born 1885, Shamrock, Missouri

Died 1983, Fulton, Missouri

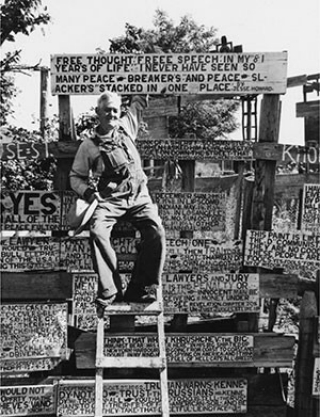

Jesse Howard once described himself as “an old dried-up farmer, wood-sawyer, sheepshearer, horse-shearer, and artist of sorts.” [1] What began as his providing publicity for a friend’s annual exhibition of steam engines and antique farm equipment turned into a regular practice by the 1950s that transformed found materials into instruments of public self-expression. Typical of his work are hand-lettered signs covering whitewashed, carefully ruled surfaces of wood or metal. Howard’s words are often accented with manicules—icons of a pointing index finger—that intensify the appeal of his boldface lettering. His individual signs voice sentiments that range from fundamentalist religious beliefs to biting political protest and candid social commentary. Seen cumulatively, his art records the unapologetic speech of a man determined to harness available materials to make his perspectives visible to any passing eye.

The signs that reside in private and public art collections today were originally part of a larger display on Howard’s twenty-acre property near Fulton, Missouri. As his roadside installation grew, it became the focus of vandalism and controversy: trespassers regularly destroyed Howard’s signs and stole farm animals, while disgruntled locals petitioned to have their outspoken neighbor institutionalized in 1952. Tellingly, the aggrieved artist named his land “Sorehead Hill.” Despite personal troubles, including a fire on his property, nothing could disrupt Howard’s tenacity: he continued to produce signs until his death in 1983.

Artist Gregg N. Blasdel was a crucial visitor to Howard’s idiosyncratic roadside display and included it in his now famous 1968 article, “The Grass-Roots Artist,” published in Art in America, the first to feature vernacular art environments. Blasdel’s text prompted many in the art world to take to the road in search of similar outdoor sites, and artist Roger Brown’s encounters with Howard in the early 1970s catalyzed development of his own expressive language as well as a photographic archive of Howard’s environment. Brown’s images serve as important visual documents of a site that no longer survives. Several of them impressed Jean Dubuffet, who later acquired a group of slides from Brown for his personal collection.

Elaine Yau

Friedman, Martin, et al. Naives and Visionaries. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, with E. P. Dutton & Co., New York, 1974.

Howard, Jesse, et al. Jesse Howard and Roger Brown: Now Read On. Kansas City: University of Missouri, Center for Creative Studies, 2005.