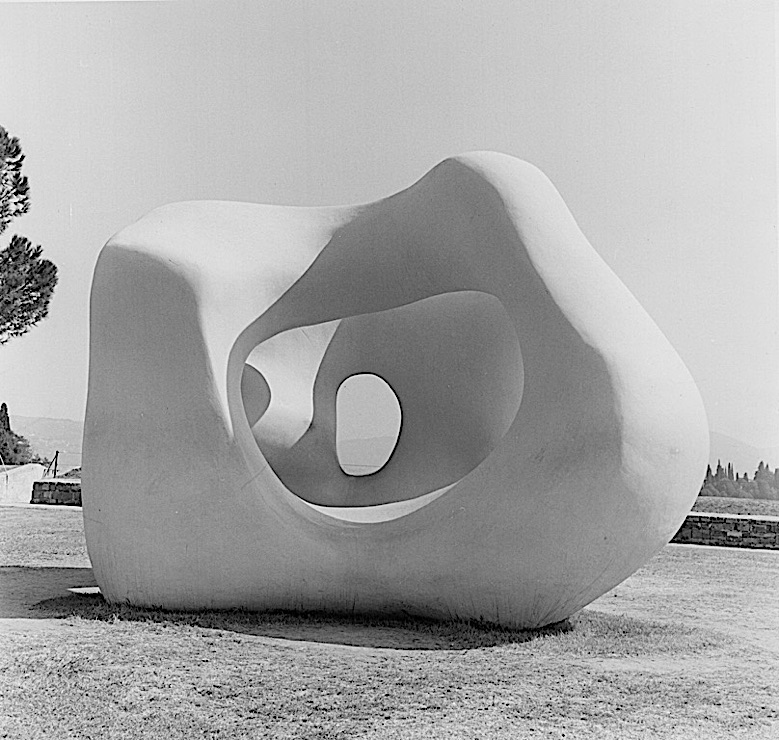

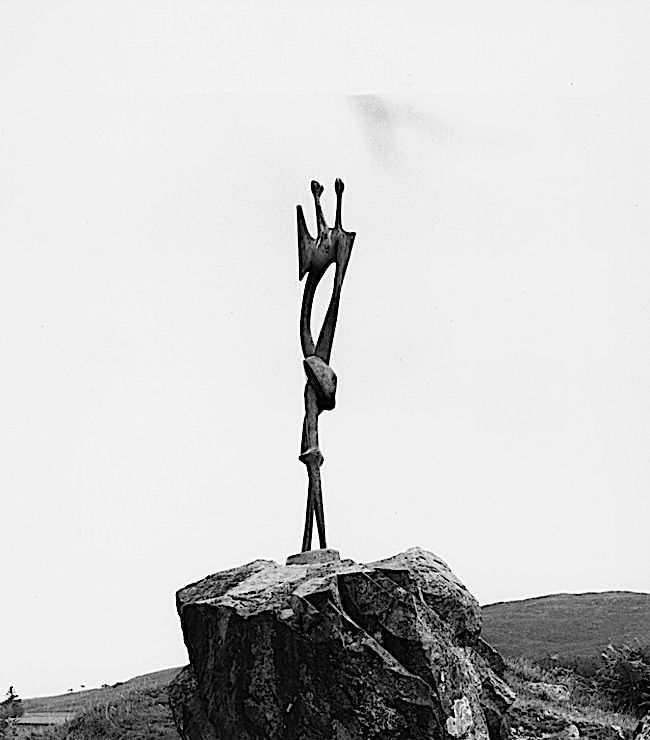

In 2016, David Finn, the world-renowned photographer and founding father of public relations, donated his photo archive to the department of image collections at the National Gallery of Art. This archive includes more than 110,000 negatives, transparencies, and images on contact sheets and more than 35,000 corresponding large photographic prints. It reflects and expands upon Finn’s photographic books and articles on sculpture and includes photographs of sculpture from all over the world made between the 12th and 20th centuries. In many cases, Finn focused his work on living sculptors—none more so than his close friend Henry Moore, whose monumental work is particularly well represented in this archive.

Moore believed that location played a crucial role in the understanding of his sculpture—that the setting surrounding a sculpture was as important to the viewer’s experience as the sculpture itself. He placed great emphasis on the importance of contrast and noted that vast, natural settings were ideal in highlighting this effect.