Release Date: March 30, 2017

Impressionist Edgar Degas Explored in Conservation Journal "Facture" Celebrating Centenary of His Death

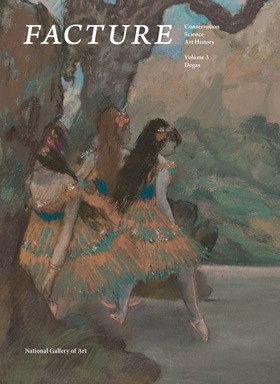

Facture: Conservation, Science, Art History, Volume 3: Degas, edited by Daphne Barbour, senior object conservator and Suzanne Quillen Lomax, senior conservator scientist at the National Gallery of Art, Washington

Washington, DC—Dedicated to Edgar Degas (1834–1917) in the centennial year of his death, the newest issue of the conservation division's biennial journal Facture focuses on the tremendous wealth of works by Degas in the National Gallery of Art's collection. The first to feature the work of a single artist, this issue includes essays by conservators, scientists, and curators. It presents insights into Degas's working methods in painting, sculpture in wax and bronze, and works on paper, as well as a sonnet he wrote to his "little dancer."

The National Gallery of Art has the third largest collection in the world of work by Degas, comprising 21 paintings, 65 sculptures, 34 drawings, 40 prints, 2 copper plates, and one volume of soft-ground etchings. Its extensive Degas holdings and conservation resources have inspired not only groundbreaking Gallery exhibitions—such as Degas, the Dancers (1984), Degas at the Races (1998), Degas's Little Dancer (2014), and Degas/Cassatt (2014)—but also exhibitions around the world. Edgar Degas Sculpture (2010), the Gallery's systematic catalog by Suzanne Glover Lindsay, Daphne S. Barbour, and Shelley G. Sturman (and also the first in that series to focus on a single artist), documents the Gallery's superb collection of sculpture by Degas through art and science.

Previous issues of Facture brought together recent discoveries by conservators, scientists, and curators on the Gallery's staff. The inaugural issue centered on Renaissance masterworks in the Gallery collection, from painting and drawing to sculpture and tapestry. Another volume considered "art in context," focusing on works from the Renaissance as well as the 20th century, from Giotto's Madonna and Child and Riccio's Entombment to paintings by Mark Rothko, sculptures by Auguste Rodin, and watercolors by John Marin. Through meticulous technical and analytical study, placed in a broader historic context, the essays provide new perspectives on well-known works of art.

Facture is available for purchase in the Gallery shops. To order: shop.nga.gov/27285/facture-conservation-science-art-history-volume-3-degas; (800) 697-9350 or (202) 842-6002; fax (202) 789-3047; [email protected]. For more information: www.nga.gov/facture

Essays

Degas and Difficulty

Richard Kendall, renowned independent Degas scholar and the only outside contributor to this volume, discusses some of the issues raised by technical examination of the artist's work and introduces the other essays in the context of Degas scholarship. Kendall explores Degas's artistic practice of seeking out difficulty, pushing himself as a painter, sculptor, printmaker, and poet.

The Question of Finish in the Work of Edgar Degas

An essay by Ann Hoenigswald, senior conservator of paintings, and Kimberly A. Jones, curator of 19th-century paintings, combines insights into Degas's compulsive working sessions and his inability to "finish" a work of art. They describe various surfaces—often found in the same work—used by Degas, who valued flexibility and potential over preservation and closure.

Edgar Degas's Wax Sculptures: Characterization and Comparison with Contemporary Practice

Degas used wax modeling to explore particular poses and gestures of female figures and horses moving through space. Based on earlier research performed for the systematic catalog on Degas (2010), Suzanne Quillen Lomax, senior conservation scientist, Barbara H. Berrie, head of the scientific research department, and conservation scientist Michael Palmer, have more precisely distinguished them from posthumous repairs and interventions.

Casting Degas's Sculpture into Bronze: A Closer Look

Daphne Barbour, senior object conservator, and Shelley Sturman, head of objects conservation, analyzed approximately 200 bronze sculptures by Degas from museum collections around the world. Building on their earlier work for the 2010 Degas systematic catalog, the authors here focus on the complex topic of the posthumously cast bronzes and summarize their discoveries in historical and technical contexts.

Technical Exploration of Edgar Degas's Ballet Scene: A Late Pastel on Tracing Paper

Michelle Facini, paper conservator, Kathryn A. Dooley, research scientist, John K. Delaney, senior imaging scientist, together with Lomax and Palmer performed an intensive study of Degas's late pastel Ballet Scene (c. 1907) that revealed his innovative use of tracing paper, charcoal, pastel, and fixative to create original effects.

In Focus: Edgar and Mary Cassatt: A Comparison of Drawings for Soft-Ground Etchings

Kimberly Schenck, head of paper conservation, studied work by Degas and Mary Cassatt (1845–1926) for the unrealized journal of etchings Le Jour et la nuit (Day and Night) and discusses the tools and methods each artist used. Focusing on the prints related to Degas's Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Etruscan Gallery (c. 1879), Schenck traces the artist's development of related images across media.

In Focus: The Little Dancer in Wax and Words: Reading a Sonnet by Edgar Degas

Alison Luchs, curator of early European sculpture and deputy head of sculpture and decorative arts, explores the ideas and emotions behind Degas's sonnet, Little Dancer (1889; revised and published 1914), addressed to a young ballerina whom he hoped would ascend the heights of her art. Luchs's analysis of verbal clues in the sonnet sheds light on changes Degas made in the course of modeling Little Dancer Aged Fourteen (1878–1881).

Edgar Degas (1834–1917)

The eldest son of a Parisian banker, Degas complemented his brief academic art training at the École des Beaux-Arts by copying old master paintings both in Italy, where he spent three years (1856–1859), and at the Louvre. Degas early on developed a rigorous drawing style and a respect for line that he would maintain throughout his career. His first independent works were portraits and history paintings, but in the early 1860s he began to paint scenes from modern life. He started with the world of horse racing and by the end of the 1860s had also turned his attention to the theater and ballet.

In 1873 Degas banded together with other artists interested in organizing independent exhibitions without juries. He became a founding member of the group that soon would be known as the impressionists, participating in six impressionist exhibitions between 1874 and 1886.

Despite his long and fruitful association with the impressionists, Degas considered himself a realist. His focus on urban subjects, artificial light, and careful drawing distinguished him from other impressionists, who worked outdoors, painting directly from their subjects. A steely observer of everyday scenes, Degas tirelessly analyzed positions, gestures, and movement.

Degas developed distinctive compositional techniques, viewing scenes from unexpected angles and framing them unconventionally. He experimented with a variety of media, including pastels, photography, and monotypes, and he used novel combinations of materials in his works on paper and canvas and in his sculptures.

Degas was often criticized for depicting unattractive models from Paris' working class, but a few writers, like realist novelist Edmond de Goncourt, championed Degas as "the one who has been able to capture the soul of modern life." By the late 1880s, Degas was recognized as a major figure in the Paris art world. Financially secure, he could be selective about exhibiting and selling his work. He also bought ancient and modern works for his own collection, including paintings by El Greco, Édouard Manet, and Paul Gauguin. Depressed by the limitations of his failing eyesight, he created nothing after 1912; when he died in 1917, he was hailed as a French national treasure. After his death, deteriorating sculptures whose existence had been unknown to all but his closest associates were found in his studio: 74 of them were cast in bronze over the next decades, and of the 70 that survived the process 52 came to the National Gallery of Art as gifts of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, including Little Dancer Aged Fourteen.

Press Contact:

Laurie Tylec, (202) 842-6355 or [email protected]

General Information

Department of Communications

National Gallery of Art

2000 South Club Drive

Landover, MD 20785

phone: (202) 842-6353

e-mail: [email protected]

NEWSLETTERS:

The Gallery also offers a broad range of newsletters for various interests. Follow this link to view the complete list.

To order publicity images: Click on the link above and designate your desired images using the checkbox below each thumbnail. Please include your name and contact information, press affiliation, deadline for receiving images, the date of publication, and a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned.

Press Release

Laurie Tylec

(202) 842-6355

[email protected]