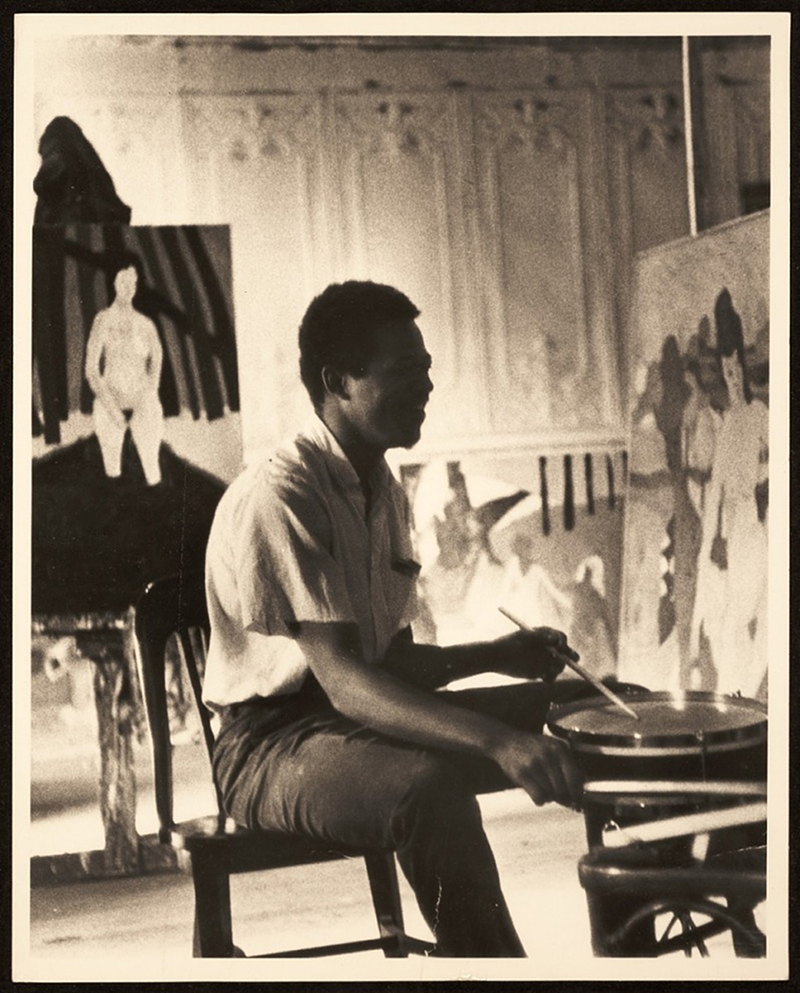

Kentucky-born painter Bob Thompson (1937–1966) was a vital part of it all. His brief but fervent career produced a staggeringly prolific body of work (over a thousand paintings and drawings) and he achieved rare success, showing in the top contemporary galleries of the 1960s. Settling in lower Manhattan in 1959, the artist fluidly moved between Beat literary and musical scenes on the Lower East Side and Greenwich Village—mingling with poets LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) and Allen Ginsberg, jazz musicians Ornette Coleman and Archie Shepp, and contributing to the earliest happenings of Allan Kaprow and Red Grooms. In the sociability of these tight-knit bohemian communities, Thompson often painted for days without resting, covering canvas after canvas “hooked” (as he wrote in a letter preserved in the Archives of American Art) “on pigment” and “buried alive” in bright colors. In May 1966, while traveling in Rome, he died from complications related to gallbladder surgery and a drug overdose.

Remarkably, and despite recognition in major museums and cultural institutions, Thompson is a curiously understudied figure in the history of art. As the Leonard A. Lauder Visiting Senior Fellow, I have been conducting research into his vast corpus, aiming to reconsider the motivations for his elision from the histories of art of the 1960s, and offering an accounting of his practice as one purposely set outside the established painterly taxonomies of the era. An abstract figurative painter who referenced the Western tradition, Thompson produced canvases that are indeed startling, not only in terms of sheer aesthetic output but in the style of his painting. An ardent admirer of old master works of the 15th through 17th centuries, throughout his short career Thompson produced inimitable appropriations (“variations,” as he called them) that aspired to the complex painterly practices of Nicolas Poussin, Piero della Francesca, and Francisco Goya. He effectively expanded recurrent motifs as points of departure to create his own private world, one that is brilliantly colored to declare a faith in nature as the source of life. From small gouaches to large oils on canvas, his oeuvre is populated by fantastic dream figures of unlocatable origins crowding the painterly space, looming next to horses, spread-eagled birds, devils, ghosts, apparitions—moods at turns grim, other times joyous. Offering a bold expressionism separated into broad, matte swaths of visionary clusters, many of his best works merge religious and mythological imagery into a singular iconography buttressed by explosive pigment and flattened forms.