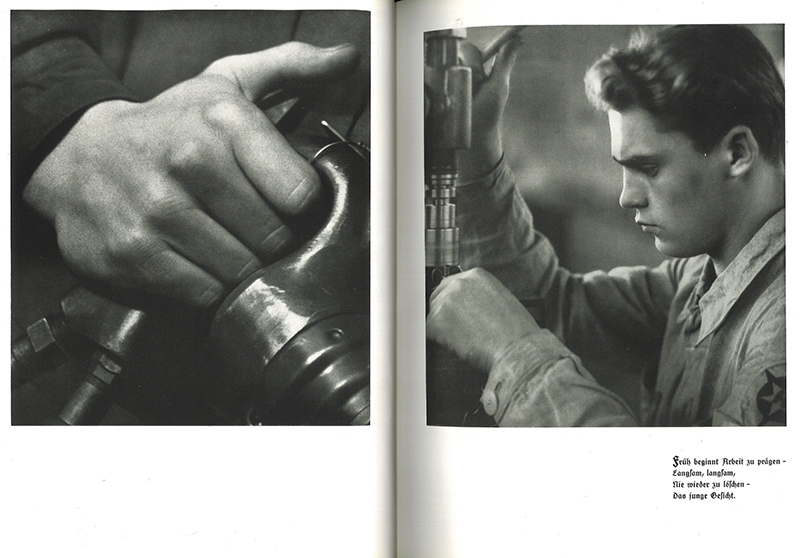

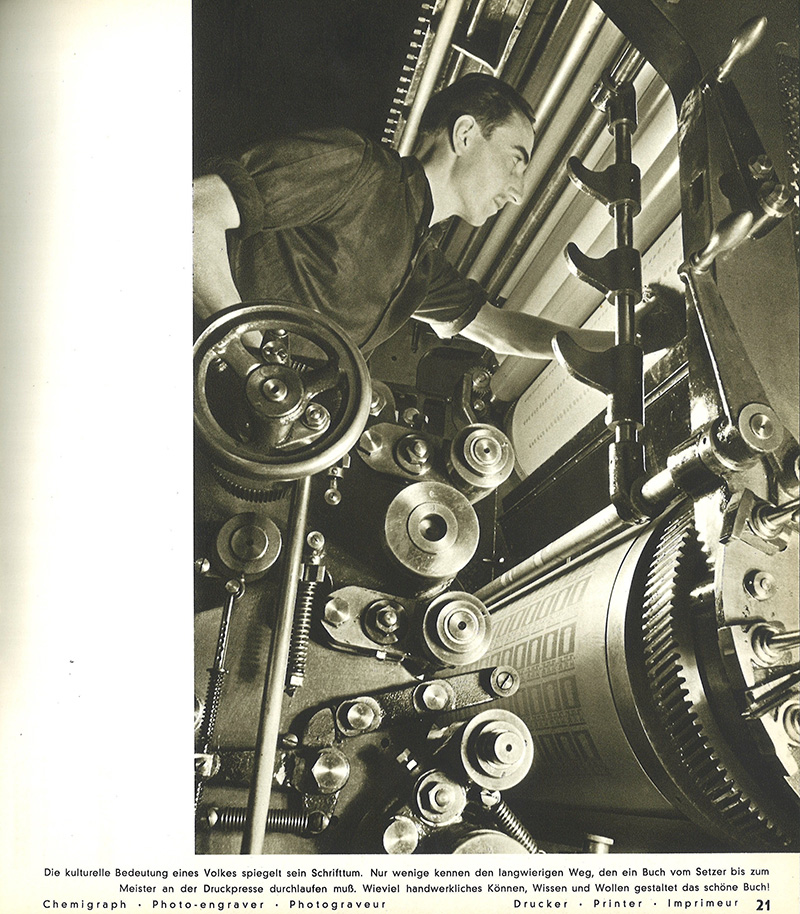

The contributions of Wolff and Lendvai-Dircksen to the discourse of Arbeitertum can be analyzed through their formal treatment of the constitutive tension between class and folk and its reconciliation in the figure of the German worker. For both, his empowerment—and he is almost always male—is predicated on the alliance between industry and state; its ultimate goal is the identity of work and folk community. Formally, these relationships are articulated through the visual framing of worker and machine, the use of composition and lighting, and the implicit assumptions about work, industry, and community as personified by the German worker. Arbeit! consists of 200 black-and-white images printed in high-quality photogravure, with descriptive captions in German, English, and French. Documentary in style, these photographs show individual workers quietly honing their skills in the optical, mechanical, and chemical industries or working together in small groups on industrial construction sites, in coal mines, and at steel mills. Commissioned by the Henschel Werke in Kassel, Lendvai-Dircksen’s book features 95 traditional portraits of blue- and white-collar workers, with only about half depicted at their workplaces. As the title suggests, “Work Forms the Face” is based on three propositions: that work, whether physical or intellectual, leaves traces on the face; that these traces can be preserved and deciphered; and lastly that they are reducible to conventional notions of social type or professional habitus. For Wolff, industrial modernity meant the merging of worker and machine; for Lendvai-Dircksen, it was an affirmation of German character. Yet, for both, the fate of industrial modernity was inseparably connected to the Nazi state—a connection that deserves closer examination, not least in order to gain a better understanding of the socialist imaginaries and racialized iconographies that survived long into the postwar years.

The University of Texas at Austin

Ailsa Mellon Bruce Visiting Senior Fellow, summer 2021

Sabine Hake will return to the University of Texas at Austin, where she is the Texas Chair of German Literature and Culture in the Department of Germanic Studies.