Alex Dika Seggerman

Art Histories of Antebellum Islam

The history of Islamic art has historically focused on lands far outside the Americas. Recently, a handful of art historians has turned their attention to the historical intersection of Islam and art in the Western Hemisphere. While Muslim communities in North and South America are small, they have been present since the arrival of enslaved Muslims from West Africa in the 17th century. Given the multi-confessional and racially diverse nature of contemporary society in the United States today, it is vital to acknowledge and study these marginalized histories.

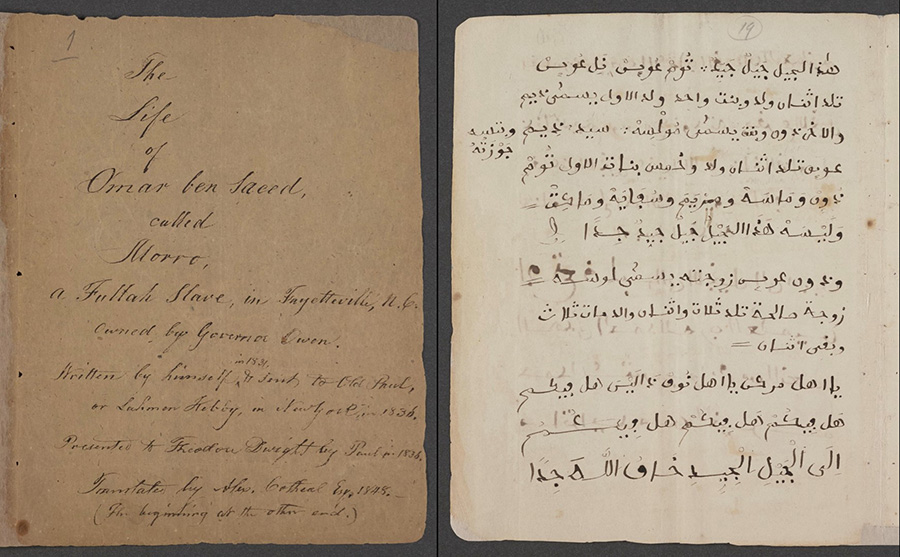

Omar Ibn Said, cover page and page 19 from Autobiography, 1831, ink on paper, Library of Congress. Courtesy Library of Congress

During my residency, I began researching a new project, “Art Histories of Antebellum Islam.” Originally, I had hoped to uncover Islamic artifacts from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Unfortunately, despite a thorough search of the collections database and a visit to the storage facility, I did not find any objects related to Islam in the museum collection from before the 20th century. This lacuna is telling, as it represents the marginalization of this history, despite the presence of at least tens of thousands of Muslims in North America before 1900.

At the Library of Congress, I analyzed the autobiography of Omar Ibn Said (1770–1863), who was born in Futa Toro, highly educated in Arabic, and enslaved in North Carolina at age 37. In the Library, many letters and translations by American Arabic enthusiasts of the 19th and 20th centuries are kept alongside Said’s 1831 autobiography. While the manuscript has been translated and analyzed by scholars, it has never been examined in an art-historical context. Through a close analysis of the original document and corresponding archival materials, I pinpointed how Said’s Arabic calligraphic techniques stem from West African traditions, establishing clear linkages among African, Islamic, and American art histories.

I also researched the oil portrait and published biography of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (1701–1773). Diallo, a noble from Bundu (located in modern-day Guinea), was enslaved in 1731 and taken to Maryland, where he continuously argued for his release. He ultimately met a sympathetic British man, Thomas Bluett, who, with the help of an Arabic letter penned by Diallo, was able to secure his transport to England and eventual return to Africa. While in England, Bluett published a biography of Diallo, and a young painter, William Hoare (c. 1707–1792), painted Diallo’s portrait, which now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London. At the National Gallery of Art, I examined a pastel portrait by Hoare to help isolate Diallo’s agency in the oil portrait. While Hoare’s portraits usually include elongated necks and shimmering eyes, the prayer callus on Diallo’s forehead and leather Qur’an case were clearly included at the sitter’s, not the painter’s, behest.

Charles Willson Peale, Yarrow Mamout, 1819, oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art

A portrait of Yarrow Mamout (1736–1823) was painted by American artist Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827) and now hangs at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Again, by comparing Yarrow’s likeness with Peale’s paintings at the National Gallery, I narrowed in on Mamout’s agency and expression of Muslim identity in the Philadelphia portrait, which lies particularly in his knit cap. Peale, who started drawing for his seamstress mother, had a keen eye for fabrics and often gave them symbolism in his otherwise straightforward portraiture. In John Beale Bordley (1770) at the National Gallery, for example, Peale portrays Bordley in American-made wool produced on his farm, a symbol of his rejection of British imports. None of Peale’s other sitters wear a cap like Mamout’s, which looks handmade. One of the lapels on Yarrow’s coat stands up, while the other lies flat, evoking his jaunty demeanor. Peale recorded how Mamout, a freed man who had been enslaved for more than four decades in Maryland, expressed his Muslim identity as a neighborhood personality in Georgetown, bantering with locals about his avoidance of pork and alcohol. Mamout, like Said and Diallo, proudly espoused his faith. In the images and texts that depict these three enslaved men from West Africa, it is abundantly clear that they advocated for their dignity through active representations of their Muslim identity and piety.

Washington, DC, was the ideal place to conduct my research because of Said’s archive at the Library of Congress, Peale’s paintings and Hoare’s drawings at the National Gallery, a print of Diallo at the National Portrait Gallery, and a portrait of Mamout at the Georgetown Neighborhood Library. Based on this wealth of primary-source research, I aim to publish a journal article in the next few years.

Rutgers University–Newark

Leonard A. Lauder Visiting Senior Fellow, summer 2022

Alex Dika Seggerman will return to Rutgers University–Newark, where she is associate professor of Islamic art history in the Department of Arts, Culture and Media. In January 2023, she traveled to North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia to continue her research on Omar Ibn Said and other African Muslims in various archives. In March 2023, she presented her new research at the Historians of Islamic Art Association Biennial Symposium in Houston.