Michele Lamprakos

Memento Mauri: The Afterlife of the Great Mosque of Córdoba

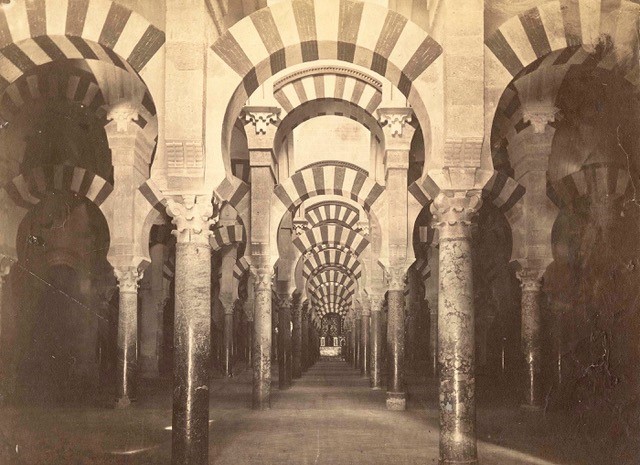

Interior view of whitewashed arches, mid-19th century, National Gallery of Art Library, Image Collections, 00016420

The Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba is a great monument of world architecture and a potent reminder of the Islamic past in Spain. Converted into a cathedral following the Castilian conquest (1236), the Great Mosque survived in a strange, hybrid form: with a towering choir-presbytery in the middle. The building’s identity—a mosque? a cathedral? both?—has long been a flash point for larger conflicts in Spanish society. Despite the vast erudition on the Great Mosque and its Christian afterlife, the building’s contested pasts and present have never been adequately explained. My forthcoming book, “Memento Mauri: The Afterlife of the Great Mosque of Córdoba,” unravels this complex and largely untold story through the lens of architecture. It explores cycles of patronage, demolition, erasure, and restoration as a barometer of changing attitudes toward the Islamic past, and the meaning of that past for Spanish culture and society. The book’s relevance extends beyond Spain to debates over the legacy and future of Islam in Europe—and to sites across the world that have been shaped and contested by different faiths.

The Mosque-Cathedral—or Mezquita, as it is still called locally—is the most magnificent of the Friday or congregational mosques that were the center of religious and civic life under Islamic rule, which lasted in various forms on the Iberian Peninsula from the eighth to the 15th centuries. When Castilian forces conquered cities (11th–15th centuries), they consecrated mosques for Christian worship. Eventually they demolished them and built cathedrals—a process that reached a fever pitch after the 1492 conquest of Granada, the last Islamic polity on the peninsula. Only Córdoba’s Mezquita survived as a functioning cathedral. But in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, two proposals were made to radically alter it; both were opposed by Córdoba’s city council and referred to the monarchs for adjudication. Finally, in the 1520s, the massive choir-presbytery (or crucero, “transept”) was begun. But, strangely, the mosque fabric around it was rebuilt, creating the hybrid structure we see today.

This architectural concept was rethought and modified over the course of the 16th century, as Islam and its legacy were erased across the peninsula. The triumphal image of the crucero was amplified and, gradually, the Islamic-era fabric was covered up or demolished.

Interior view after restoration, mid- to late 19th century, National Gallery of Art Library, Image Collections, DLI 06163133244

But from the early 19th century, just decades after the mosque fabric was fully “Christianized,” the process was reversed: the Mezquita was “re-Islamicized.” In the era of Romantic restoration, bishops and, later, state architects uncovered, restored, and sometimes reinvented the Islamic fabric. For liberals and republicans, the restored Mezquita represented an alternative national narrative: that of a multi-confessional society which had been erased by a fanatic alliance of church and state. Recovery of the Islamic fabric also intersected in surprising ways with Spain’s imperial ambitions in North Africa. Paradoxically, the process reached a high point under the ultra-Catholic dictatorship of Francisco Franco (1939–1975): as part of his “Arab policy,” he quietly revived a republican proposal to remove the crucero and rebuild the missing mosque fabric. In the early 1970s, this secret initiative exploded into a public controversy as preparations were made to nominate the building for UNESCO’s World Heritage list. It was defeated and the Mezquita was reinvented, however improbably, as a symbol of “cultural pluralism.” But the story does not end there. The crucero was rehabilitated, first discursively and then architecturally. Soon increasingly conservative Catholic Church officials would begin to “re-Christianize” the monument, downplaying, discrediting, and even denying its Islamic past. Citizen activists fought back against what they saw as an attempt to erase historical memory, a struggle that continues today.

My residency allowed me to advance this book manuscript, providing dedicated research and writing time, as well as access to the National Gallery of Art Library and the Library of Congress. During my time at the Center, I researched and wrote a chapter on the final stages of construction of the crucero and the progressive erasure of the Islamic fabric. I consolidated my thinking about design proposals and construction campaigns during this period, and how they relate to debates over Islamic legacy and the fate of the Moriscos (descendants of Muslims converted to Christianity who were expelled from Spain in 1609–1614). My work was greatly enriched by exchanges with colleagues at the Center, and by the generous help of librarians and archivists. The National Gallery’s image collections, in particular, contain a precious photographic record of the Mosque-Cathedral in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, documenting its transformation during that period.

University of Maryland, College Park

Paul Mellon Visiting Senior Fellow, fall 2022

Michele Lamprakos will return to her position as associate professor at the School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation at the University of Maryland, College Park. She has been awarded a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship (2023–2024), which will enable her to complete her book, to be published by the University of Texas Press.