Zsofi Valyi-Nagy

Vera Molnár’s Programmed Abstraction: Computer Graphics and Geometric Abstract Art in Postwar Europe

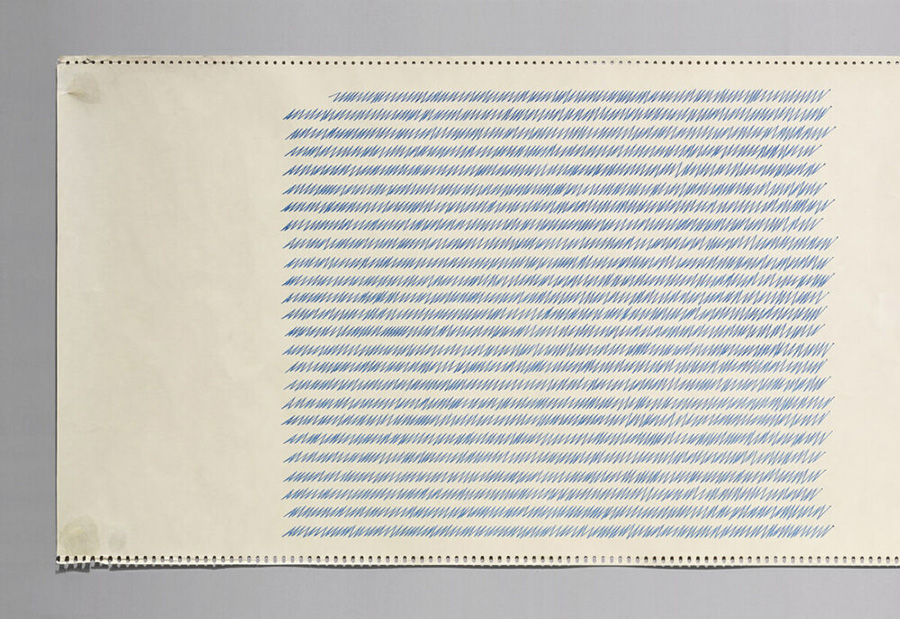

Vera Molnár, Lettres de ma mère (detail), 1988, plotter drawing in india ink on Calcomp roll paper, overall: 30 × 450 cm, Musée de Grenoble. Photo: Jean-Luc Lacroix

How do you draw a line with a computer? Before the advent of programs like Paint, this seemingly simple task required technical knowledge of computer programming. My dissertation traces the computer-generated line in the work of the Hungarian-born, Paris-based artist Vera Molnár (b. 1924), one of the first visual artists to experiment with computer graphics beginning in 1968. While Molnár’s career spans the entire postwar period into the 21st century, I focus on her “computer-aided” painting practice, as she called it, from the 1960s to the early 1990s. As digital art has been siloed into histories of “new” media art, my wider aim is to contextualize these practices, particularly within the history of geometric abstract painting.

Even before she turned to electronic computers, Molnár’s work was already programmed, her thinking already computational. By looking closely at her process, through a combination of archival research, interviews, and media-archaeological “reenactments” of her work, I examine how Molnár used computers to ask many of the same questions dominating painting and intellectual discourse in postwar Europe: What was the role of the author or artist? How could subjective choice be eliminated from the creative process? Could machinic seriality reinvent painting? Could a machine make art?

At a moment when computers were threatening to displace, and ultimately replace, humans with their artificial intelligence and robotic arms, Molnár used these machines to study her own subjectivity, to examine what aspects of the creative process could not be automated. “It may seem paradoxical,” she wrote in a text titled Léonard de Vinci s’il eût eu un ordinateur (Leonardo da Vinci, if he had had a computer; 1989), “that the so-called inhuman machine helps to realize what is most subjective, what is most profound in man.”

During the first year of my fellowship, I worked with media archaeologists at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, who view the history of technology not as a teleological progression, but as a dynamic network of machines and processes that are waiting to be reactivated. They study obsolete technologies by fixing them up and using them, and by considering the ways in which their histories are inscribed into them, such as the palimpsest of vector graphics on the screen of a Tektronix microcomputer from the late 1970s, which we used to reprogram Molnár’s artworks. “Reenacting” Molnár’s computer graphics through retrocomputing (using period hardware and programming languages) allows us to better understand how the work was made and what it was like to make it. I suggest that Molnár’s computer-aided practice was not simply about generating images; it was also an extended aesthetic experiment, a means to deconstruct and demystify the creative process.

Stefan Höltgen and Zsofi Valyi-Nagy reenacting Vera Molnár’s Lettres de ma mère on a Tektronix 4052 microcomputer, Signallabor, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, June 2022. Photo: Julia Sandor, Artykfilm

While in residence at the Center, I had the opportunity to revise and present a dissertation chapter focused on my media-archaeological reenactment of Molnár’s series Lettres de ma mère (1981–1991). Offering a “simulation” of her late mother’s handwriting in computer-generated asemic writing—marks that look like writing but say nothing whatsoever—Molnár’s work, in turn, involved a process of reenactment. I consider how this artwork challenges, even pokes fun at, the traditional connection drawn between an artist’s marks and their psyche, the individual “genius” embedded in the brushstroke or pen line. What do we make of handwriting simulated by a computer program, executed by the robotic arm of a plotter machine that “draws” with a small pen? Authorship and temporality are thrown into question as the connection between the artist’s hand and the work of art is short-circuited. And yet, Molnár’s title invokes a deeply personal relationship between her and her mother. Reading between the lines of these “letters,” I consider the potential—and the failure—of abstraction to obscure the personal, and the tensions between my interpretation of the work as an art historian and what Molnár offers, both in her art and in her own words.

Building on years of conversations with the artist, I call my method “critical oral history.” This means acknowledging that the artist’s words are one of the richest sources of historical documentation—especially in these cases where their work has been systemically marginalized or overlooked—while also considering factors like self-mythologizing, aging, memory, and trauma, as well as the relationship between the artist and the historian and, of course, my own positionality.

University of Chicago

Twenty-Four-Month Chester Dale Fellow, 2021–2023

Zsofi Valyi-Nagy will spend the 2023–2024 academic year as a postdoctoral fellow at the Getty Research Institute under the annual theme “Art and Technology.”