Isolating architectural production as a distinct art-historical subject brings into focus basic questions foundational to the social history of art. Above all, it asks how we can mediate between works of art and structural conditions of society. By looking at large numbers of buildings and patterns in the building industry, such a focus also calls on evidence best suited to digital methods of analysis. My project thus explores the premises of both social art history and digital mapping through an investigation of construction activity in Germany between the world wars, one of the most dynamic phases in the history of modern architecture. In this long view of construction, I examine when buildings were built, their functions, and their locations at a much greater scale than previous art-historical scholarship. Locating and categorizing thousands of structures, from modest vernacular industrial sites to the most monumental of forms, provides a basis for investigating how construction engages with the broader political economy and social conditions of Germany from the Weimar Republic through the demise of the Nazi state. Such an approach also refocuses art- historical questions on a much larger swath of “dark matter” (to use Gregory Sholette’s formulation) surrounding the few stars of modernist architecture that all too often form the limit of what we analyze as building in the period.

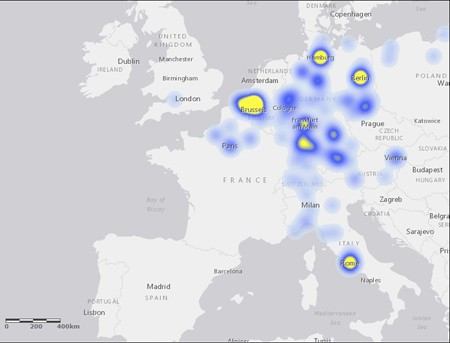

To get at this question, I have spent my first year as the Andrew W. Mellon Professor constructing a database of building activity, focusing on World War I and its immediate aftermath, up to economic stabilization in 1924. In collaboration with my colleague, CASVA research associate Ivo van der Graaff, I have developed a database to extract information from contemporary sources, starting with the professional architectural journals of the period such as Deutsche Bauzeitung and Baumeister. Compiling this information allows us to begin mapping the results, using geographic information system (GIS) technology. GIS enables queries of the database that show us otherwise invisible patterns of development. For example, the spread of building activity in rural areas well beyond the major urban centers and the emergence of typological clusters of structures both become more perceptible. Such activity is indicated in a draft map that shows, as concentrations of yellow nodes, areas of particular interest to the editors of the Deutsche Bauzeitung but also indicates, in the blue expanses in between, sporadic reference to other geographies of building activity completely invisible in standard art histories that focus on such known locations as Berlin and Munich. The mapping project in this case is part of the research process, not a final representation of results. Rather, we will use the database and subsequent maps to see what patterns arise in the temporal and spatial distribution of construction in Germany. Such patterns will then form the basis for further research, for instance, in municipal records of particular locations marked by intense activity.

Over the summer, we will continue work on the database and explore archival source material that can be layered onto the map (for example, voting patterns or labor demographics). In addition, I will begin to identify case studies in both construction histories and architectural careers that can be employed to highlight aspects of the larger questions. I will, for example, be working in the Siemens-Archiv in Munich, since the Siemens Bauunion was one of the largest construction firms of the interwar period. Bringing these strands together into a final manuscript next year will form the first part of the much larger study of the construction industry through the end of World War II. Ultimately, this project seeks to provide a rich and deep political- economic context for major monuments and figures in interwar German architecture. More important, it models the way in which digital methods instantiate social art-historical questions that in turn critically challenge a potentially limited and canonically driven analysis of this crucial cultural and political period in modern Germany.