Isolation in Pablo Picasso’s "Family of Saltimbanques"

The painting shows us the ambiguity and loneliness of life on the outskirts of society.

Have you ever seen a jester look so sad? Or a group of circus performers without a big tent in sight?

Saltimbanques are street acrobats. The word combines the Italian saltare—to jump—with banco—bench, platform, or stage. But the figures in this eerie painting seem to float above the ground in a strange, barren landscape. And the pale colors and thin layers of paint add to a vague, dreamlike feeling. These people appear trapped in limbo, stuck in a state of uncertainty.

Austrian poet Ranier Maria Rilke was struck by the unsettling, sad mood of Family of Saltimbanques. In a poem about the painting, he asked, “Who are they, these wanderers, even more transient than we ourselves?”

We may ask the same question—who are these people? Where are they? And, importantly, what is Picasso trying to tell us?

Picasso Moves to Paris

In 1904 Spanish artist Pablo Picasso moved to Paris. At first, he struggled to establish himself there. He was an immigrant in a large, rapidly industrializing city. The painter was also under surveillance by the French police, who suspected him of anarchist leanings and foreign sympathies. The ambivalent, lonely feeling of Family of Saltimbanques may reflect these difficult experiences.

But Picasso did quickly bring together a group of artists, writers, and other creatives known as “la bande à Picasso.” This loose collective included painters Juan Gris and Georges Braque, as well as poets Max Jacob and Guillaume Apollinaire.

In this painting, Picasso may be connecting the saltimbanques with his own group of misfits. They stand—or seem to hover—on the outskirts of Paris, just as his bande occupied the outer ring of Parisian society.

A Cast of Circus Characters

Also during his first years in Paris, Picasso began attending performances at the Cirque Medrano in the artistic, bohemian neighborhood of Montmartre.

The circus featured clowns, acrobats, and stock characters from the commedia dell’arte, a popular form of theater that originated in 16th-century Italy. Picasso began drawing and painting the dynamic scenes of the Cirque Medrano and eventually got to know some performers.

Here, he includes a few well-known figures from the commedia dell’arte tradition.

Unanswered Questions

Some elements of this work remain mysterious.

The Painter Makes Changes

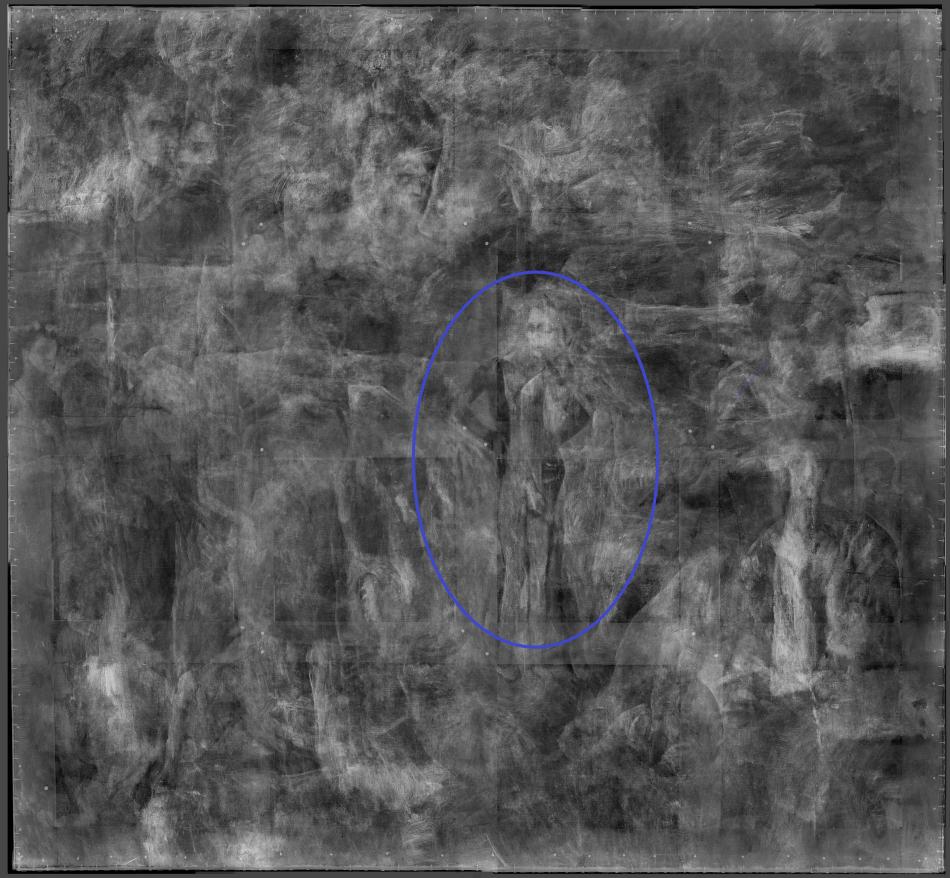

While we can learn much from the painting in its current form, conservation research has revealed that Picasso made several changes.

In preparatory studies for Family of Saltimbanques, Picasso placed the figures in front of an action-packed horse race. He painted himself not as a harlequin but as a gentleman wearing a suit and carrying a briefcase. Picasso sketched other arrangements of figures. In one, a boy balances on a ball.

X-rays under the surface of the painting reveal that he painted the balancing figure on the canvas before painting over it.

In the final composition, Picasso has isolated the characters from their craft as circus performers. They stand still, without any clear purpose, movement, or direction. He has also removed them from society; they are truly alone in the landscape.

By the early 1920s, Picasso would find success in Paris and gain international fame. But at the moment when he created this painting, he seemed to identify with the outcasts of society.

You may also like

Interactive Article: Layers of Power in "The Feast of the Gods"

At first glance, this painting looks like a great party. But it’s more complicated than that.

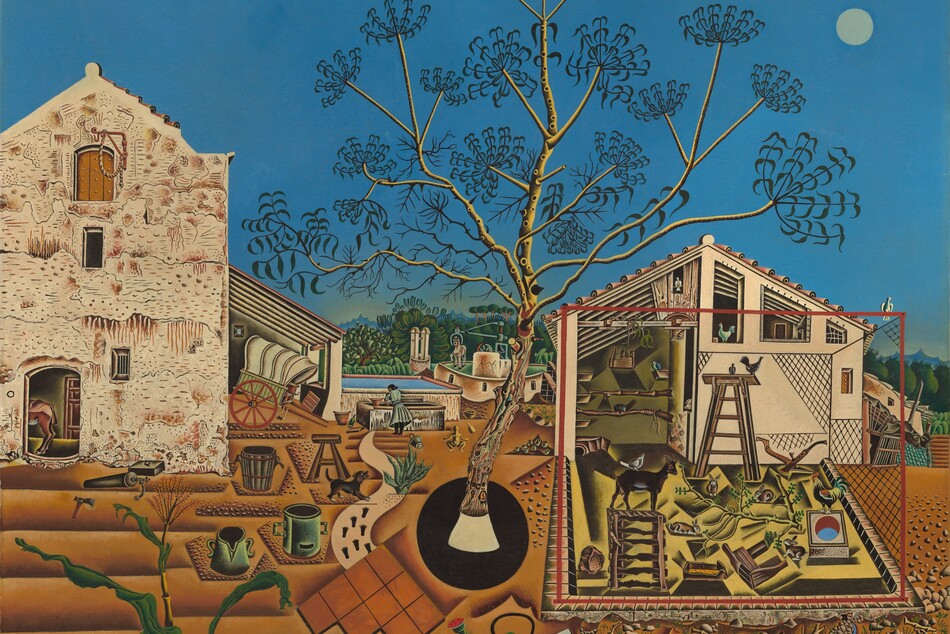

Interactive Article: Art Comes to Life in Joan Miró’s "The Farm"

Joan Miró’s complex and captivating painting is full of life and mystery.