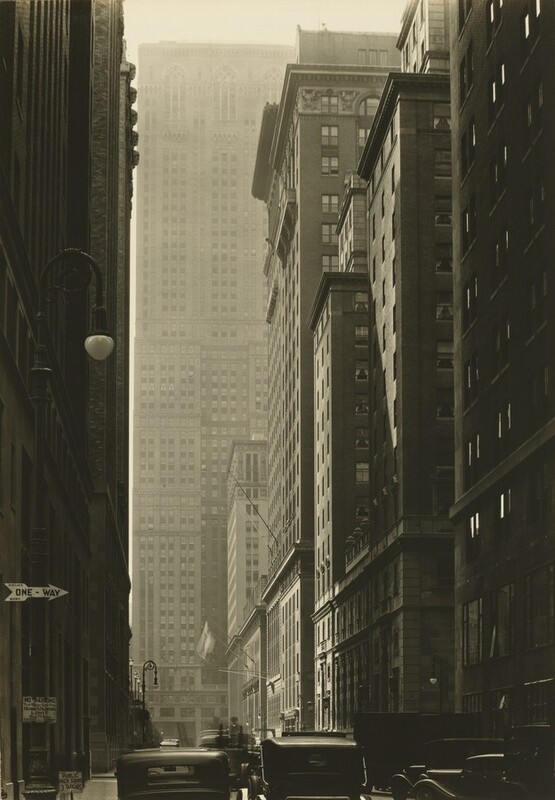

Vanderbilt Avenue from East 46th Street

October 9, 1935

Berenice Abbott

Artist, American, 1898 - 1991

In 1921, Berenice Abbott left New York City's bohemian Greenwich Village and moved to Paris to study sculpture. Like many of her fellow expatriates, Abbott was disenchanted by the rise of American commercialism after World War I and eager to join the artistic and literary milieu of Parisian café society. Financial difficulties and a serendipitous meeting with the artist Man Ray in 1923 led her to photography: Man Ray hired Abbott, a novice in the medium, to work as his darkroom assistant. Although she took the job primarily to support herself, she soon saw photography as a viable means for creative expression. By the time she left his employ nearly three years later, Abbott had earned a reputation as an esteemed portrait photographer and was able to establish her own studio on the Left Bank.

In 1929, Abbott returned to New York to find a publisher for her book on the French documentary photographer Eugène Atget.1 Seized by a newfound passion for the city, she decided to remain in the United States and embark on an ambitious documentary project: photographing New York in its entirety, from newly constructed skyscrapers, to private residences, tenement houses, civic centers, transportation systems, bridges, and city streets. Securing financial support proved difficult at first, but Abbott's determination paid off when in 1935 the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration agreed to sponsor her work. The project, published in part in the 1939 book Changing New York, reflects Abbott's mature documentary aesthetic. Informed by the sharp tonal contrasts and considered compositions of European modernism, as well as by a commitment to the "extraordinary potentialities" of an American subject, Abbott's photographs of New York City reflect her desire to interpret her subjects "honestly," "with love void of sentimentality, and not solely with criticism and irony."2

Abbott photographed Vanderbilt Avenue from East 46th Street in the first month of the Changing New York project. Located in the vicinity of the Grand Central Terminal complex, on the middle east side of Manhattan, the five-block-long avenue was lined with graceful, austere brick-and-limestone skyscrapers that rose to heights of thirteen to sixteen stories. The avenue typified the kinds of architectural canyons that reshaped the island of Manhattan during the city's skyscraper boom in the first decade of the century. With a brilliant understanding of architectural geometry, Abbott emphasized the verticality of the skyscrapers, aligning edges of buildings and windows while arranging street signs and car roofs as perfect horizontal counterpoints. By allowing a sliver of sky to appear between the dark foreground and lighter background buildings, Abbott opened the scene to a cascade of light that pours across façades and trickles off tiny windowpanes. At street level, the ghosts of moving cars and waving flags testify to a human presence and time's passage. The scene avoids claustrophobic tension or a sense of human alienation. Instead, Abbott presented the city as an organic whole, a formal organization of the "living and functioning details of a complex social scene."3

As determined by its paperboard mount, this particular print of Vanderbilt Avenue from East 46th Street was one of 111 photographs in the one-person exhibition Changing New York, which opened in October 1937 at the Museum of the City of New York. The show, Abbott's second one-person exhibition at the museum, garnered critical acclaim and brought the artist recognition from a broader general public. The exhibition, its related press, and the 1939 book fostered a turning point in Abbott's career, elevating her from the status of a relative unknown to that of an art-world celebrity.

(Text by April Watson, published in the National Gallery of Art exhibition catalogue, Art for the Nation, 2000)

Notes

1. Abbott met Atget through Man Ray and became a regular visitor to the elderly photographer's studio. A fervent admirer of his documentary style, Abbott dedicated herself to promoting his work. Upon his death in August 1927, Abbott purchased a sizable portion of his collection, including over 1,400 glass negatives and 7,800 prints. See Peter Barr, "Becoming Documentary: Berenice Abbott's Photographs, 1925–1939" (PhD diss., Boston University, 1997), 126.

2. From Abbott's application to the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation in 1931, as quoted in Bonnie Yochelson, Berenice Abbott: Changing New York (New York, 1997), 13 (note 19).

3. From a letter written by Abbott to her Federal Art Project supervisor M. J. Kauffman, as quoted in Barr 1997, 243 (note 38).

Artwork overview

-

Medium

gelatin silver print

-

Credit Line

The Marvin Breckinridge Patterson Fund for Photography and Robert B. Menschel Fund

-

Dimensions

overall: 23.7 × 16.5 cm (9 5/16 × 6 1/2 in.)

-

Accession Number

1998.65.1

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

(Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York, NY); purchased with donated funds from Marvin Breckinridge Patterson by NGA, 1998.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1999

Photographs from the Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1999.

2000

Art for the Nation: Collecting for a New Century, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2000-2001.

2015

In Light of the Past: Celebrating Twenty-Five Years of Collecting Photographs at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, May 3 – July 26, 2015

Bibliography

1997

Yochelson, Bonnie. Berenice Abbott: Changing New York. New York, 1997: sec. Middle East Side, pl. 22.

Inscriptions

all on mount: lower center verso in graphite: Vanderbilt Ave (from E 46 St) / neg #10 code IA2 / taken Oct 9, 1935; all by later hands: upper left verso in black ink: 600; lower center verso in graphite: FF19323

Wikidata ID

Q64145156