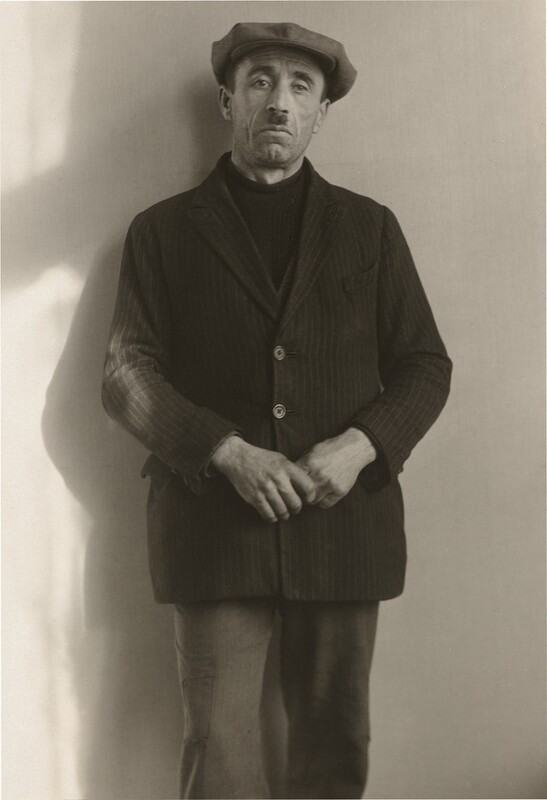

Recipient of Welfare Assistance

1930

August Sander

Artist, German, 1876 - 1964

August Sander's Recipient of Welfare Assistance exemplifies his mature style at its finest: simply composed, unaffected, and direct. It is part of a monumental series that consumed him for nearly a quarter of a century: using the "universal language" of photography to record members of all professions and social classes, Sander attempted to "arrive at a physiognomic definition of the German people."1

Sander became fascinated with photography when, as an adolescent apprenticing in an iron mine in the small, west German village of Herdorf, he was called upon by the foreman to assist an itinerant photographer. With financial assistance from an uncle, he purchased his first camera, and over the next few years he worked in several photography studios. In order to produce the "artistic" portraits his clients favored, he mastered the gum bichromate and other painterly processes in vogue at the time, though he preferred more direct, naturalistic studies.

In 1910 Sander opened his own studio in the Cologne suburb of Lindenthal, where he specialized in "simple, natural portraits that show the subjects in an environment corresponding to their individuality."2 To attract business, Sander bicycled every weekend to Westerwald and photographed the peasants there. These Westerwald farm portraits later became the foundation for his large documentary project.

In the early 1920s, Sander met artists such as Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Otto Dix, Anton Räderscheidt, and Wassily Kandinsky. Their stimulating discussions led Sander to realize the importance of his project, which he renamed "Man of the Twentieth Century." He began to make portraits expressly for the series3 and to sift through his earlier negatives, which he recognized for the first time as a treasure trove of pictures tracing the psychological makeup of the individual and society. He devised a hierarchical order, with the peasant as the foundation of society, high-level professionals and the upper classes at the top, and the homeless and infirm at the bottom. To symbolize the universal scope of his project, he identified his subjects by occupation or position, not by name.

In 1929, Sander published Face of Our Time, a selection of works from his series. The critically acclaimed book was hailed as "a case of the camera looking in the right direction among people," providing "a photographic editing of society, a clinical process; even enough of a cultural necessity to make one wonder why other so-called advanced countries of the world have not also been examined and recorded."4 The clarity of his images allied Sander with the new objectivity advocated by other contemporary artists, including Albert Renger-Patzsch, whose The World is Beautiful had been published the year before.

Sander projected that his "Man of the Twentieth Century" series would encompass up to 600 photographs. However, his view of physiognomy was at odds with the Nazi ideal, and in 1934 the Nazis destroyed the printing blocks of Face of Our Time and seized all available copies. Sander's archives were repeatedly searched, and many negatives were either confiscated or later destroyed in a fire set by looters. Although forced to abandon his project at this time, Sander was able to resume work after the war; he continued to photograph subjects and print from old negatives until he succumbed to a stroke at the age of 88.

(Text by Julia Thompson, published in the National Gallery of Art exhibition catalogue, Art for the Nation, 2000)

Notes

1. August Sander, "The Nature and Growth of Photography, Lecture 5: Photography as a Universal Language." Reprinted in The Massachusetts Review (Winter 1978), 677.

2. Advertising brochure, c. 1910. Reprinted in August Sander: Photographs of an Epoch, 1904–1959 [exh. cat., Philadelphia Museum of Art] (Philadelphia, 1980), 17.

3. As late as 1921 Sander used the gum bichromate process; after 1922 he used gelatin silver papers. Because they were coated with a layer of white pigment mixed with gelatin (the "Baryta layer"), these papers produced prints with a smooth, reflective surface and brilliant highlights.

4. Walker Evans, "The Reappearance of Photography," review of Face of Our Time, Hound & Horn 5 (October/December 1931), 128.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

gelatin silver print

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

sight size: 22.3 x 15.4 cm (8 3/4 x 6 1/16 in.)

-

Accession Number

1999.49.4

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

The Estate of August Sander, Cologne; by inheritance to Gunther, then Gerhard Sander, Cologne; Private Collection; (Kathleen Ewing Gallery, Washington, DC); purchased by NGA, 1999.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

2000

Art for the Nation: Collecting for a New Century, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2000-2001.

2015

In Light of the Past: Celebrating Twenty-Five Years of Collecting Photographs at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, May 3 – July 26, 2015

Bibliography

1989

August Sander, Citizens of the Twentieth Century: Portrait Photographs, 1892-1952. Cambridge [Massachusetts], 1989: 407.

Inscriptions

on mount, lower right in graphite: Aug. Sander / Köln 1930; by later hand, on mat, lower center verso in graphite: #6 ERWERBSLOSER FRANZOSE

Markings

BS: Sander

Wikidata ID

Q64145065